Since the North Carolina legislature approved hydraulic fracturing, more commonly known as fracking, in July 2012, state representatives have debated how to move the process forward.

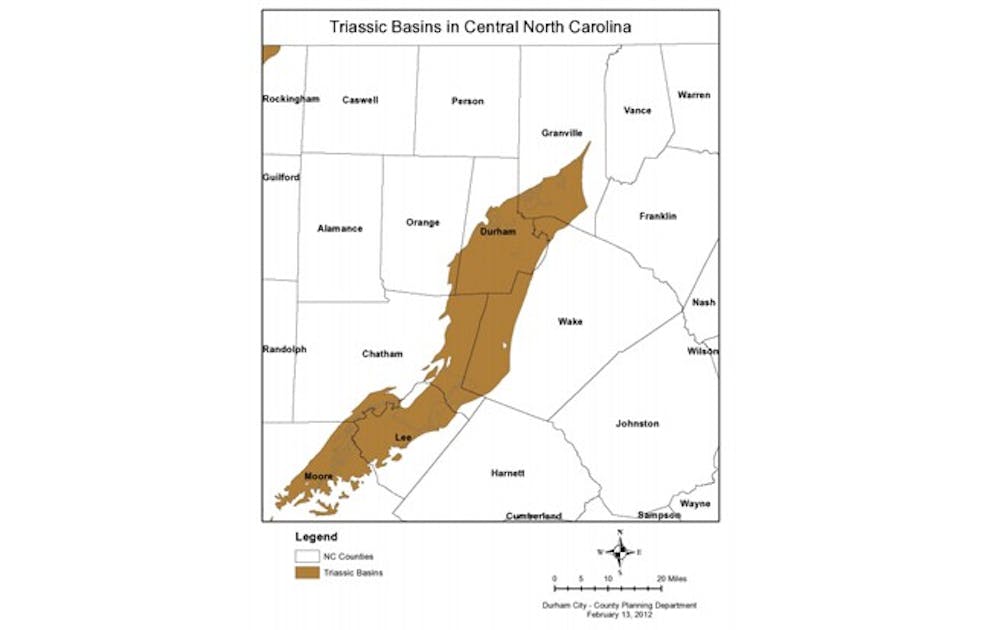

Despite the bill’s approval, drilling in the state will not occur for several years until safety regulations are put in place. The conversation regarding fracking occurred after the discovery of a large shale gas basin in North Carolina. The shale basin, which spans across Moore, Lee, Chatham, Wake, Granville and Durham Counties, has been targeted by companies who hope to drill and harvest the energy stored within the rock. Experts believe that less-developed counties will be targeted first, because the financial benefits of fracking will be higher there.

“It’s less likely in Durham,” said Brian Miles, chair of the Durham Environmental Advisory Board. “They’re going to go where the costs are lowest, and there is a chance of negative public perception, so they’ll probably go to the rural counties. They’re more used to working in those environments.”

The bill’s approval means that fracking will be ready to go as early as 2014, but it will be up to each county to determine whether it will participate.

Fracking, which involves drilling both vertically and horizontally to access deep rock layers, uses explosive charges and high pressure fluid to induce fractures in the rock in order to release the natural gas and oil stored inside. This fuel can then be brought back to the surface, at which point it is harnessed and sold. Although fracking may lead to a substantial revenue boost in drilling neighborhoods, the techniques used to access this fuel introduce possible environmental dangers that could threaten the health of North Carolina residents, causing state representatives to consider safety regulations. Duke researchers are at the forefront of studying the pros and cons of fracking and what it means for North Carolina.

No longer ‘clean energy’

For a time, hydraulic fracturing was the face of clean energy, a far more environmentally friendly alternative to previous coal mining practices, said Avner Vengosh, professor of geochemistry and water quality at the Nicholas School of the Environment, who is currently conducting a large-scale study on the effects of fracking nationwide.

“When shale gas and fracking started, many environmentalists saw it as the clean future of energy,” he said. “In fact, several large environmental groups, like Sierra Club, were supporting it. Now they’re realizing that there are some issues [with fracking] and they are going back from that.”

The main environmental threat from fracking, ignoring secondary problems such as noise and air pollution from truck traffic and on-site generators, is water contamination. For his research, Vengosh and his colleagues have gathered over 700 water samples from places like Pennsylvania and West Virginia, where nearly a thousand new sites are drilled each year. He has found that contamination, if identified, can come from both methane gas leakage and wastewater disposal.

When the flammable greenhouse gas methane leaks from fracking pipelines into groundwater, water sources can become saturated with it, making kitchen sink pyrotechnics a real possibility.

Additionally, the dumping of liquid waste can contaminate ground water sources, creating toxic drinking water.

“We see [in the wastewater] that there are man-made chemicals, high salinity and naturally occurring radioactivity released from the formations,” Vengosh said.

Fracking companies are exempt from the Clean Water Act, which regulates the discharge of pollutants into water systems, so companies are not required to disclose how many and what chemicals they put in the ground. Companies claim that revealing the formulas would allow competitors to copy their techniques and take away profits, but the secrecy also makes it harder to study where the harmful fluids end up, Vengosh said.

“The natural gas industry is powerful,” said Rebecca Vidra, lecturer and director of undergraduate studies for environmental science and environmental science and policy. “[It] has many friends in Washington.”

New technologies may help increase the transparency of the fracking industry in the future, allowing targeted areas to make more informed decisions. BaseTrace, a company started by a team of five Duke graduate students and Alumni, seeks to address the question of how to track fracking fluids by developing a DNA-based tracer that would be added to fracking fluid. If it is later detected in general water sources near a fracking site, it would indicate a leak, said Justine Chow, CEO of BaseTrace and Nicholas ’12.

An economic boom with pitfalls

Despite the disputed nature of fracking’s environmental effect, it brings employment opportunities and increased revenue that can stimulate growth in an otherwise underdeveloped area.

“One of the things [fracking] will do is probably raise the value of all the houses in the town because there’s a lot of well workers and an increased demand for housing,” said economics professor Christopher Timmins, who is studying the effects of shale gas development on property values.

In addition to the neighborhood’s economic growth, many individual households will also receive direct compensation by leasing contracts with companies that want to drill on their property.

“It varies dramatically, but some people can become millionaires if they get lawyers and [negotiate] with fracking companies correctly,” Vengosh said.

According to one of Timmins’ current working papers, “upon signing their mineral rights to a gas company, landowners may receive two dollars to thousands of dollars per acre as an upfront “bonus” payment, and then a 12.5 to 21 percent royalty per unit of gas extracted. Such incentives make it difficult to resist the advances of the energy industry.

The expected economic boom accompanying fracking, however, is not without its pitfalls.

In his research, Timmins looked at over 19,000 pieces of property in Washington County, Pa., to study how living within 1.25 miles from a shale well will influence property value. He found that houses within this radius experience an 11 percent property value boost as a result of signing leases with fracking companies.

Because properties closer to fracking sites are subject to possible water contamination, however, houses within this radius that are at risk of water contamination experience a 24 percent lower increase in property value when compared to houses not at risk.

Vengosh said he worries that a lack of financial sustainability may also be a problem for fracking towns.

“You might see a boom town symptom, where you have a lot of money going into some sector but not into the infrastructure, so when [fracking] is finished, everything will collapse again,” he said.

Timmins added that the change in composition of a town’s businesses as a result of fracking may also negatively effect a town’s economy. If a town’s economy depends on tourism, that may go away as a result of fracking, causing the town to re-evaluate its revenue source when there is no more fracking.

Pricing ‘negative externalities’

Although fracking has the potential to cause environmental damage, it is important to note that this is not always the case.

“Many people saw the movie Gasland and take it almost religiously that fracking contaminates water, but that’s not true every time,” Vengosh said.

He added that such contamination depends on whether pipes do leak and if the companies choose to dump wastewater illegally.

Timmins took an economic approach to the matter, arguing that if there are negative effects from drilling, fracking companies should incur the cost of those damages.

“I’m not opposed to the idea of using natural gas… but if we find out that there are negative externalities associated with it, we should make sure we price that—maybe by taxing it, to make sure that the drillers incur the cost if they’re imposing any,” he said. “Then we let the market take care of the rest.”

Miles said that a severance tax on natural gas supplies to help fund pre- and post-drilling monitoring programs would be essential to future fracking endeavors, but doing so would require significant investment from the state to start up the monitoring program.

Miles is also concerned that North Carolina may face a higher probability of experiencing environmental damage from fracking than places like Pennsylvania, because shale basins are shallower, increasing the potential for interaction between ground water and possible contaminants.

Either way, county representatives in North Carolina still have a lot of factors to consider regarding fracking in their respective areas. There do not appear to be any plans for fracking in Durham currently.

“I plan to live here for a while,” said Timmins. “It doesn’t seem like it’ll happen soon but… who knows?”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.