Lost amid an otherwise embarrassing stretch for the NCAA was that the organization made its biggest step forward under President Mark Emmert early last week.

The progress is less of a leap and more of a stumble, but for once it reflects a modicum of self-awareness from the NCAA.

Well, sort of.

The good: The NCAA changed 25 regulations from its Stone Age rulebook to reflect what the rest of the country knew years ago: It cannot control the more than 400,000 athletes at 1,000 member schools the way David Stern governs the NBA or Roger Goodell oversees the NFL.

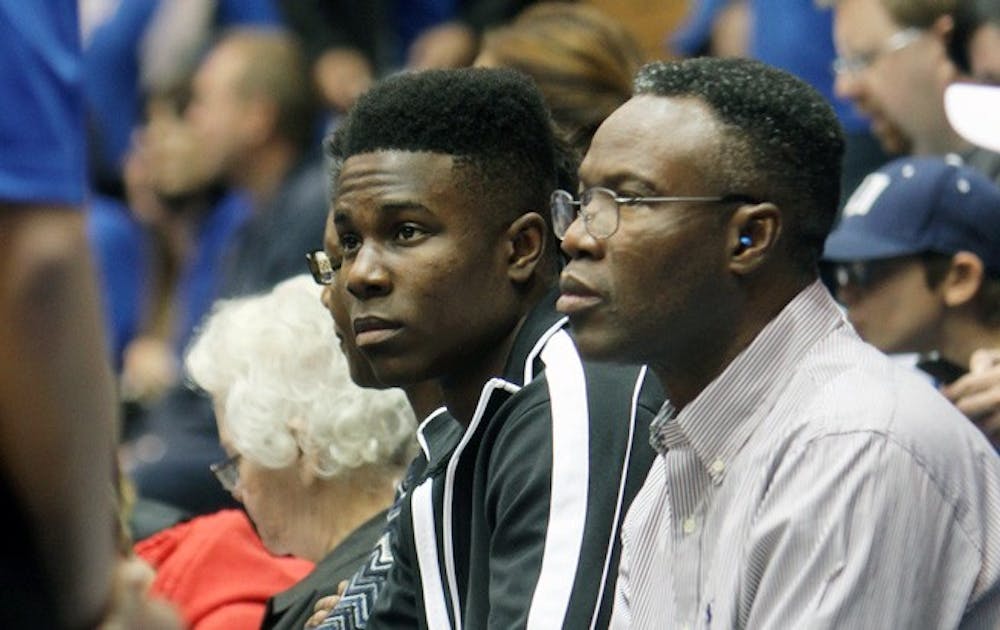

(Why? Because professional sports don’t have to worry about maintaining amateurism. Stern doesn’t have to chase down Kevin Durant outside a press conference to ask him how he could afford a Gucci backpack, as the NCAA did with UCLA’s Shabazz Muhammad and Kyle Anderson last week—a move that reeked of sour grapes after the organization’s earlier mishandling of an investigation into Muhammad’s recruitment.)

The bad: The changes will widen the ever-growing competitive gap in collegiate athletics.

The ugly: The new rules won’t matter if the NCAA has no credibility, and the organization certainly lost the little it had left after its ethical transgressions in investigating Miami.

The changes are the result of nearly 18 months of analysis done by a Rules Working Group of college presidents commissioned by Emmert in August 2011. Of the 25 modifications, two are poised to become the most controversial over the next few years. Rule 13-3, which will come into effect July 1, “will eliminate restrictions on methods and modes of communication during recruiting.”

In combination with rule 11-2, “which will eliminate the rules defining recruiting coordination functions that must be performed only by a head or assistant coach,” recruiting is now a whole new ballgame. Coaches can now text recruits as much as they want, whenever they want and even hire a recruiting coordinator (or recruiting staff!) to deal with the details.

It’s a move that ends any pretense of creating competitive balance in college athletics. Alabama’s football program can now use part of the $45 million profit it made in 2011-12 to hire a full staff to text, call, email, send letters, write postcards and send messenger pigeons to each one of the school’s targets 50 times a day. It’s unfair to Boise State and other low-budget hopefuls, but did anybody really believe that competitive balance still existed? Nine of Yahoo Sports’ top 10 football recruiting classes last season went to schools that ranked in the nation’s top 15 in athletic department spending, and the lone outlier was Miami, which isn’t exactly strapped for cash.

The real reason this move should be seen as progress, though, is that the NCAA finally realized it had no way to enforce the contact limitations it had in place. The organization employs about 40 investigators who rely largely on unsolicited tips and sources around the country for information on infractions. They can access only publicly available information and lack subpoena power, and thus can only interview those willing to talk to them. It’s an impossible job, which is why the decision to deregulate the uncontrollable violations was so necessary.

The real losers—as always with the NCAA—are the athletes themselves. Somewhere along the way, coaches nationwide decided the only way to show a recruit how much they cared was through the quantity of contact, rather than the quality. Nick Saban famously sent a recruit 100 letters in a single day, ostensibly to demonstrate the almighty power of Alabama football. Now athletes will be subject even further to a novelty that wears off quickly as the boxes of form letters pile up in the living room.

If these rule changes are all about enforceability and streamlining the process, though, then it’s time to face the elephant in the room head on: Amateurism. Just as the NCAA can’t possibly police the actions of hundreds of thousands of players and coaches nationwide, it has no means of preventing Shabazz Muhammad from accepting money to play at UCLA—or apparently, of effectively investigating the issue.

It’s not the solution the NCAA wants, considering its whole existence is reliant on an endless supply of free labor, but it’s the realization it’ll have to come to if it plans to continue paring down its rulebook by eliminating unenforceable laws.

Last weekend’s announcement was a relatively strong step forward for an organization that has seemingly been springing in the wrong direction for the last two years, but I’ll remain unimpressed until they actually tackle the biggest issues facing college athletics.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.