Researchers have broken ground on how living near fracking sites influences property value.

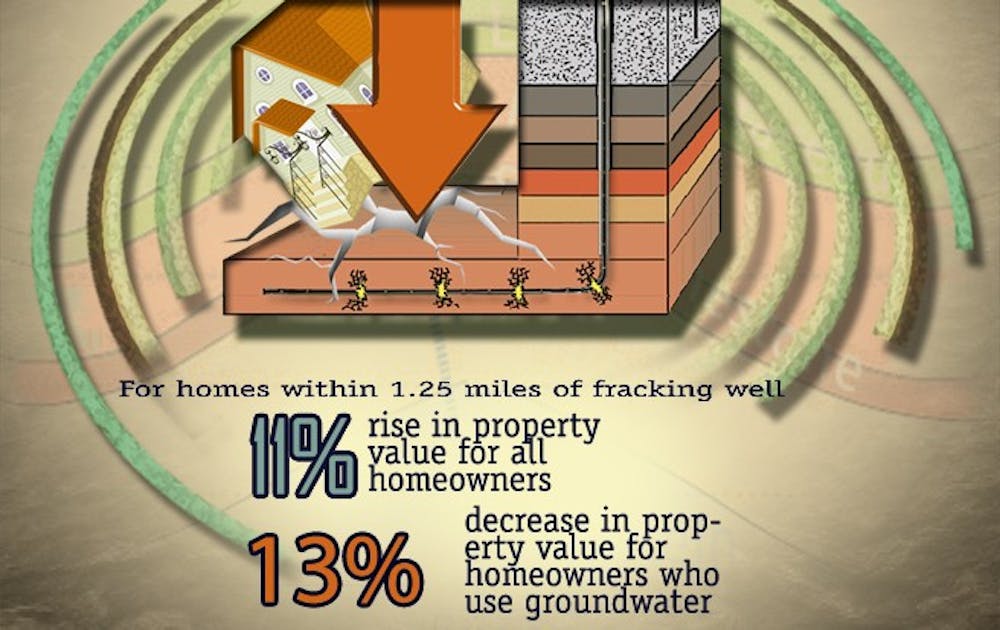

Fracking—a technique used to extract natural gas in shale formations—has faced both criticism for its potentially harmful environmental impacts, such as contaminating groundwater, and support for its potential to provide more fuel and promote economic development. Duke researchers looked at over 19,000 pieces of property in Washington County, Pa. to study how living within 1.25 miles from a shale well will influence property value. They found that homes dependent on piped water had an increase in their property value and those that depended on ground water saw a decrease as a result of living near a fracking site.

“It’s really difficult for the public to understand the impact of shale gas development if we don’t research the subject,” said Elisheba Spiller, co-author of the study and post-doctoral research fellow at Resources for the Future, an environmental policy group. “We want to spark discussion but also demonstrate there are positive and negative impacts from shale gas development.”

Christopher Timmins, co-author of the study and professor of economics, said that houses within the roughly one-mile radius experience an 11 percent property value boost because the fracking utility cannot drill without the homeowners signing a lease. The lease payments and potential economic development add overall value to their homes.

The study also found, however, that homes risk losing some value if they are located near shale wells and depend on groundwater, which comes from wells on the property.

These homes’ property values decrease because homeowners are unsure whether their water is contaminated by shale wells and have to account for that when drafting a cost for their home. The possibility of contaminated water forces the property value to decrease by an average of 24 percent, which offsets the boost from signing a lease and leave a net decrease in value of 13 percent.

“We don’t want to say people using groundwater aren’t getting any benefits, but those benefits are overshadowed due to the possible risks of contamination,” Spiller, who graduated from Duke in 2011 with a Ph.D. in economics, said. “Overall the economy is booming, but there are still unfair issues —some people are being hurt by it.”

Homes that depend on pipe water, therefore, are only positively affected by living near shale wells since their property values increase from the lease payments.

Timmins, who is also a research associate in the environmental and energy economics group at the National Bureau of Economic Research, noted that these estimates are all relative to homes outside the 1.25 mile radius.

Spiller noted that it is very difficult to clean groundwater once it gets contaminated since the water usually cleans itself by filtering through rocks. She recommended that the government either increase regulation of fracking or expand the pipe water network to those using groundwater near shale wells.

Although regulation would be costly, Timmins said it is worthwhile to decrease the risk of groundwater contamination and help homeowners who bear extra costs as a result of living near a fracking site.

“We’re underpricing gas right now because we don’t force [fracking companies] to incur these costs, but homeowners are taking on those costs,” he said.

Currently, fracking is regulated at the state level and has many loopholes, Spiller said. For example, fracking is not regulated under the Clean Water Act, so companies do not need to disclose how many and what chemicals they put in the ground.

“They are basically free to do what they want,” Spiller said. “There are some regulations on surface water issues for sites larger than five acres… but the regulations are really sort of spotty,” she said.

Although shale wells cannot be built without members of the community signing leases allowing the drilling, Spiller noted that as long as a few people sign a lease, it is in other neighbors’ best economic interests to sign as well, since they will have to put up with noise and air pollution of the plant anyway.

“There’s never going to be a case where it makes sense for someone to not sign a lease,” she said. “Unless everyone really banded together and signed a binded contract [against fracking], gas development is going to move forward.”

Avner Vengosh, professor of earth and ocean studies, said the perception that groundwater is contaminated from fracking is largely speculative. Although some groundwater wells in Pennsylvania contain methane, it is unclear whether this leakage comes from the shale wells.

“When people talk about contamination from hydrofracking, it’s sometimes misleading,” he said. “We think it’s contaminated, but it could be naturally occurring and have nothing to do with shale gas development.”

Even if people with groundwater wells have measured their water quality, often they did not do so prior to the creation of a shale well, making it unclear whether contaminants actually came from the fracking site.

Faculty and graduate students are trying to build tools that will enable homeowners to see if contaminants are naturally occurring or come from fracking, Vengosh said.

As long as there is a perception that groundwater wells could be contaminated as a result of fracking, however, homeowners with groundwater wells will be negatively affected because they will have to accept a lower price as long as a risk of contamination exists.

“We need to think about who is bearing the cost [and] make sure those people are protected,” Spiller said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.