Scientists have determined that brain structure may play an important role in developing post-traumatic stress disorder.

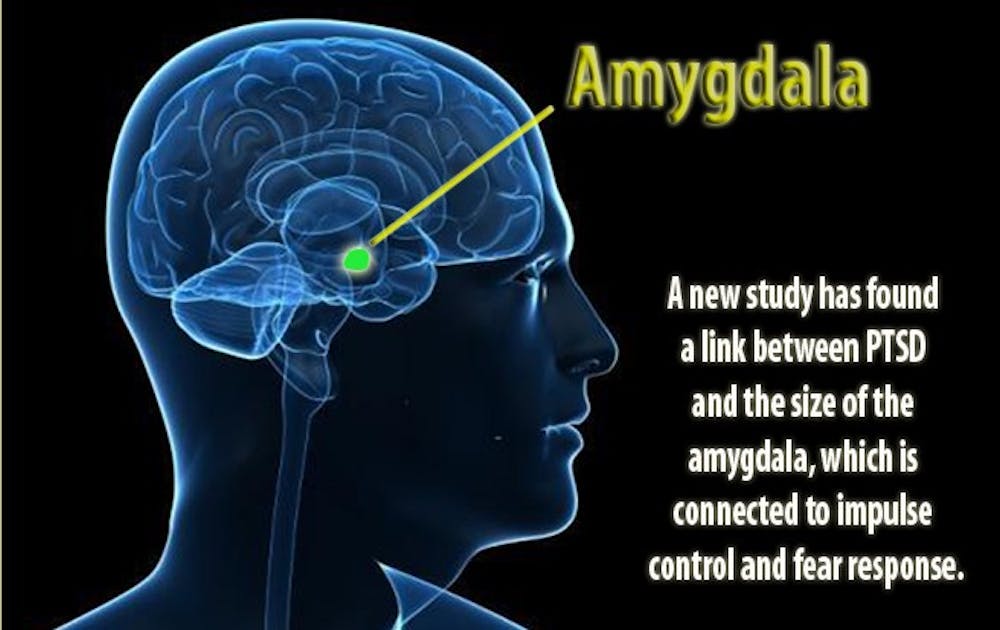

A study released Nov. 5 by a team of scientists from Duke and the Durham VA Medical Center has determined a link between the size of the amygdala, a structure in the brain associated with impulse control and fear response, and the presence of PTSD in recent combat veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The article, published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, found that the veterans with PTSD had a smaller amygdala volume.

“We know that the amygdala is important to PTSD because it is important in how we process fear and perceive what’s threatening in our environment,” said Dr. Rajendra Morey, lead author of the study and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral science.

PTSD is a severe anxiety disorder that can develop in individuals who have seen or experienced an event that causes psychological trauma, such as domestic abuse, assault and war. Symptoms of the disorder include reliving the trauma through flashbacks or nightmares, avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and difficulty concentrating. Nearly seven percent of the general population is believed to have the condition.

Incidents of PTSD occur in many veterans who served in combat roles. Nearly 14 percent of combat veterans serving in Iraq and Afghanistan have developed PTSD, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The researchers studied 200 combat veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan after Sept. 11, 2001. Although all of the participants had been exposed to trauma before the study, only half of the veterans had PTSD. The study examined the volumes of the amygdala using MRI scans of all the participants.

Even though the study did link the size of the amygdala to PTSD, it did not determine what conclusively led to the smaller brain structure.

“We don’t know if people who have smaller amygdalas go on to develop PTSD [after exposure to trauma] or if the [exposure] leads to a decrease in the size of the amygdala,” said Kevin LaBar, co-author of the study and professor of psychology and neuroscience.

Morey stated that the data is more consistent with the idea that people with PTSD may have a smaller amygdala prior to trauma exposure, which may predispose them to developing the disorder. The researchers did not observe a trend suggesting that the amygdala changed in size as a result of the frequency, duration or severity from the trauma.

A variety of factors could potentially affect the size of the amygdala, ranging from heredity and nutritional issues during gestation to environmental issues.

The discovery of the link between amygdala size and PTSD could play a factor in determining occupational roles in the military, LaBar said.

“If it can be established that this is a contributing factor for developing PTSD, we may be able to use this as a screen test so it may help us in assigning [people with smaller amygdalas] to jobs in the Army that would make them less exposed to trauma,” he said.

The results from the study are not expected to have an impact on treatment options for those suffering from PTSD, which currently consist of medication and group therapy, said Dr. Gregory Weiss, a physician in the Mental Health Service Line at the Durham VA Medical Center.

“While medicine can help control some of symptoms, such as jumpiness, psychotherapy is still the gold standard,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.