A study conducted by Duke researchers empirically shows for the first time what many pediatricians have suspected for a while: children are largely underrepresented as subjects in clinical trials.

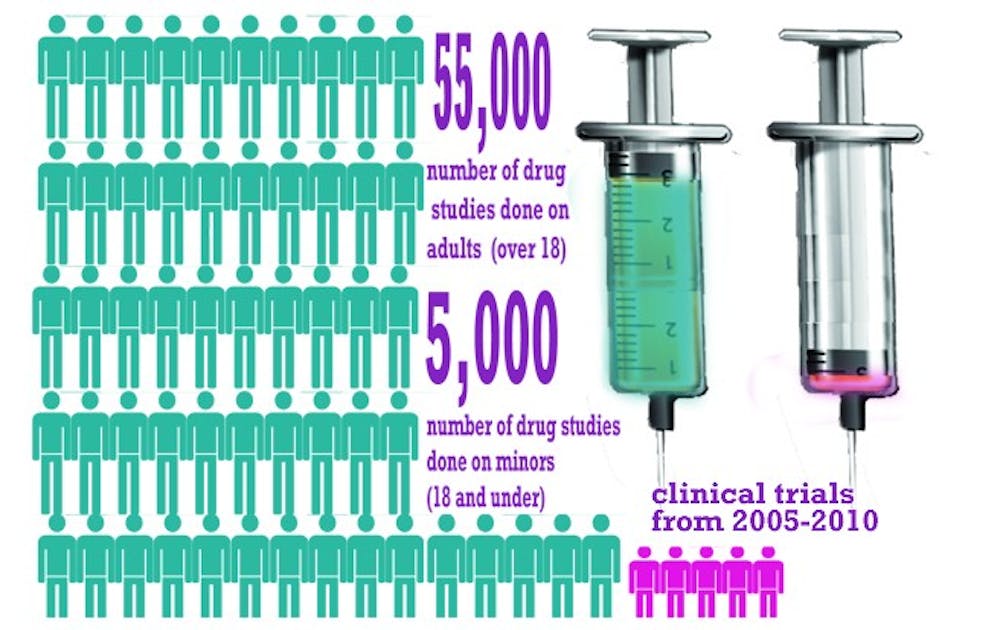

Published Oct. 1 in the journal Pediatrics, the study analyzed more than 60,000 clinical trials from 2005 to 2010 listed in the public database clinicaltrials.gov. The researchers found that, although children under 18 make up nearly 25 percent of the overall population, clinical trials used children in only about 8 percent of the studies.

“It’s something we knew qualitatively and that we talked about, but this really quantifies for the researcher the nature and the scope of the problem,” said Dr. Danny Benjamin, principle investigator at the Pediatric Trials Network, which is based at Duke.

Clinical trials are the best way doctors can learn how to best treat their patients, said Dr. Alex Kemper, a pediatrician at the Duke Clinical Research Institute and author of the study. Doctors learn what treatments are safe and what amount of drugs are effective through clinical trials, but children are underrepresented in these studies. He added that even if children are included in clinical trials, there are often too few of them for the results to be conclusive.

When there is no specific clinical trial data on which treatments work best in children, Kemper said, pediatricians try their best to interpret how a treatment affects children by looking at data from adults.

“It can be dangerous when we make these assumptions,” Kemper said.“Children are not little adults—if you’re extrapolating a study that was done on a 70-kilogram adult to a two-kilogram baby, there’s a chance that you’re either not dosing appropriately or that you’re going to have unexpected side effects.”

Using children in drug studies poses several problems that could account for the disparity.

One such issue is that children cannot give informed consent to being used in a study. Instead, parents must decide whether their child can enroll in a trial. Getting informed consent from families can be difficult, Kemper noted, but it is “too easy” to blame that factor alone for low child representation in trials.

“I can tell you from talking to many families of children with serious health conditions that they would love the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial,” he said. “But we haven’t made the opportunity available for those kinds of important studies to be done.”

Historically, companies and federal agencies running complicated, expensive drug studies have had little incentive to study the effectiveness and safety of drugs in children because they get sick less often than adults, Benjamin said. Before 1998, there was no law that required drugs to be tested on children in order to be approved by the Federal Drug Administration.

Congress expanded the focus on pediatric trials in 2007 with the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, which gives pharmaceutical companies longer patent protection for drugs in exchange for testing how those drugs work in children.

Despite addressing monetary concerns, pharmaceutical companies still find it difficult to recruit enough children to enroll in trials because illnesses are often rarer in children than they are in adults.

Clinical trials that do include children are often so small that the data from them is unclear, said Dr. Micky Cohen-Wolkowiez, a pediatrician at PTN.

To find enough patients, researchers have to recruit children from multiple hospitals or networks of clinics, which adds costs and makes trials for children more challenging than studies for adults, Kemper said. Still, doctors must strive to provide appropriate care for children despite these barriers, he added.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.