Though the buzz of sirens, horns and nearby construction work pollutes the air around the church garden at the corner of Dillard and East Main Streets, to the sleeping residents of the garden benches the din is merely background noise. For them, the garden offers solace, serenity and a place to sleep in the sunshine during daylight hours. Despite its title as “Church Garden,” the small, circular plot of land hosts mostly weeds, caked dirt and the bench dwellers, clinging to garbage bags filled with their personal possessions.

Just outside the garden’s confines, Steve Murray cannot sleep and instead aimlessly paces around the area. His royal blue fleece stands out against the muted grey clothing of his peers, who seem to blend in with the lackluster garden structures. Steve, a short, aging black man with a rough voice but a bright smile, is one of the many homeless residents who spends his time on this corner. Urban Ministries of Durham—one of the local shelters—sits at the next intersection and is connected to the church. On most spring days, Steve can be found wandering the area, sometimes chatting with other Urban Ministries residents—whom he refers to as his “socials”—but otherwise spending his time in solitude.

“I hang out by myself most of the time. I don’t like to deal with the crowds,” Steve explained. “I’ve got a lot of ‘socials’ around here, but all my real friends have moved out of Durham.”

Despite his current lack of a physical address, Steve has called Durham home for almost all of his life; he moved to the Bull City to stay with his grandparents at age 6 and has been a resident ever since. Steve grew up on Roxboro Road and attended Lakeview School, an alternative education program for students with chronic misbehavior or problems with long-term suspension. Steve’s connection to the city has always been strong. Having loved it growing up, he worked on the construction of many of the central public buildings—like the Durham Courthouse and the Durham County Library—that are now so intrinsic it is hard to imagine Durham without them. While walking through the library, Steve proudly points out the walls he structured and the wings he helped build, but struggles to read the name of the sections like the Dr. Benjamin E. Powell Memorial Room, one of his favorites.

Walking toward Urban Ministries, Steve greets his UMD neighbors warmly as they call out to him. As they pass, however, he said he tries to keep himself separated from their “crowd” because he thinks he has a better employment ethic.

“I do whatever I feel like—whatever moves me,” he said. “I work odd-end jobs, sometimes people come pick me up and give me a job for two or three days. You’ve got to keep out of the woods, you know? Keeps me apart from the riffraff.”

These days, though, finding work is more of a challenge. As a homeless man in his late fifties, job opportunities have begun to dwindle.

“I’m not old enough to be retired,” he said. “But I ain’t young. I don’t work as often as I used to. But I try.”

State of Homelessness in Durham

Homelessness is neither a small nor unfamiliar problem in the Bull City. Once a booming center of tobacco and textile manufacturing, Durham’s economy is not what it was in the days of James B. Duke. As the presence of these industries has long-since waned, many still feel the void of their absence and the city’s economy has never fully recovered.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, almost 18 percent of Durham residents were living below the poverty level—an annual income of less than $22,314 for a family of four—in 2010. What’s more, in January 2011 the North Carolina Coalition to End Homelessness reported that 652 people were homeless in the county at the time. While this number showed a 23 person decrease since the previous year, it was still indicative of the drastic increase Durham has recently seen. In January 2009, the homeless population was 535—marking a difference of 117 people in only two years, and an almost five-fold increase since 2001. Based on these figures, Durham had the fifth highest homeless population in the state last year.

One of the most apparent issues confronting homeless residents like Steve is unemployment. Ryan Ferhman, the executive director of the Genesis Home—an agency that specifically focuses on assisting families as they transition out of homelessness—said unemployment is one of the main factors he sees that prevent families from “graduating,” or finding permanent housing outside of the organization.

“One of the biggest challenges for just about every family in the house is employment and income,” he explained. “It’s been a huge issue. Without the jobs, it’s hard to get the folks out…. It’s a very real challenge we face in the shelter.”

In a survey conducted last spring among the county’s homeless population, a lack of jobs proved to be the dominant problem. Among those surveyed, 53 percent did not have paying jobs. And of those who did—14 percent—more than half said theirs were only part time. When asked what service would have prevented their situation, 50 percent answered “help finding a job.” Additionally, almost a third of individuals who managed to obtain permanent housing after homelessness indicated that they wanted “help getting trained or upgrading education.”

“A lot of the response was ‘I need a job, I need a job, I need a job,’” Ferhman said about the results. “It was crazy to read some of the comments, people are desperate to work.”

The recent recession has only added to the problem and is a large factor in the drastic increase in the homeless population since 2009.

“There’s been a really high demand for services that we’ve seen over the last couple of years since the recession,” Ferhman said. “One of the things we track is shelter nights [the number of people over a span of nights during which people utilize the facility]…. It’s a basic indicator of occupancy. For 2011 the number of shelter nights provided was at an all time high in the history of the agency since 1989.”

For Jason, a current long-term resident of Urban Ministries who chose to withhold his last name, the recession was the tipping point that drove him into homelessness. Jason is a 41-year-old white man from Morgantown, N.C. who graduated from Georgetown University in 1994 with a double major in history and English. Based on his appearance, though, one would hardly guess he has a degree from one of the country’s most prestigious colleges. He is tall, wears a tattered black baseball cap, a worn faux-leather jacket and ripped jeans, and is missing half of his right front tooth.

Jason’s arrival at the shelter is the result of a combination of failed jobs and bad luck. He left Georgetown with a desire to pursue independent film production after getting involved with the school’s improv club his junior year. After a brief stint working as an assistant manager for Simmonds Precision Company in New Jersey, which closed in 1996, Jason decided to return to the D.C. area and to his original goals of working in film His girlfriend at the time had just left to travel abroad, and the timing seemed right. Because the production industry is largely project-based and offered inconsistent work opportunities, Jason held a series of part-time jobs—first as a Starbucks barista and then as a restaurant valet—to make ends meet. When his girlfriend returned from overseas, though, Jason followed her to Syracuse, N.Y. in hopes of, yet again, pursuing film. Not long after, the two went through a bad split and, with no real career opportunities in sight, Jason found himself out of work. Returning to his home state, he came to Durham to enter the real estate business in 2008—just as the recession was about to hit the area with full-force.

By 2010, Jason was in a bleak situation. Jobless, newly evicted and without a car, he moved into a church-based homeless shelter near Morgantown. He was directed to Urban Ministries last summer and has been there ever since. “At first, I had planned on just toughing it out here until February when I had heard the market was supposed to pick up,” Jason explained. “But now it’s not supposed to get better until mid-summer. I’ve been talking to places on Ninth Street and in Brightleaf Square [for employment], but it’s tough because for them to reach me they have to call UMD, and it’s not a great spot to call back.” Jason started as an “overnighter” at UMD, which meant entering the line for a bed every day at 3:30 p.m. The shelter only gives overnight residents a 60-day stay period, though, and at day 45 with no solution in sight, he knew he had to find another option. He is now a member of the Journey Program, a long-term service for residents who don’t need assistance with disabling conditions.

“It’s hard because I’m one of the only folks who has been to college who’s here right now,” he explained. “Most people here have issues with substance abuse.” Every day, Jason wakes up at 6:30 a.m. in the main bunkroom with the other residents. They are served breakfast until 8 in the neighboring cafeteria, then forced to leave UMD until lunch is served at 11. After that, overnighters are required to leave again until the afternoon line-up, and Jason showers and starts his day. The timing limits his job-searching window to 12-5 p.m., though, during which he has to allow himself an hour walk to and from potential employers and UMD. Instead, most days he stays near the shelter and goes to different hotels or the library to use the public computers. It’s hard to connect with other people at UMD, he said, because his situation is so different than those of most other residents.

“I’m friendlier with the folks who work [at UMD], honestly,” he said. “Most people here are either overnighters or in the substance abuse program. It’s too tough [to relate to them] because with substance abuse you want to give them room to work on that.”

For now, Jason plans on staying at UMD and testing the waters in mid-summer when the real-estate industry will hopefully offer more opportunities. If that doesn’t work, he’s not sure whether he’ll stay in Durham or go back to Washington, D.C.

Seeking Refuge

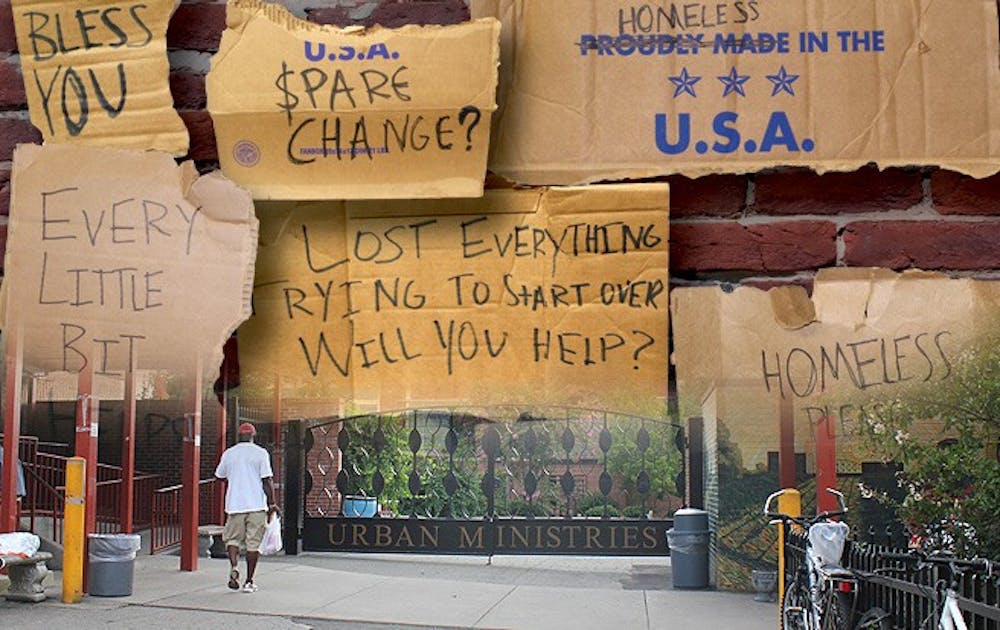

Urban Ministries of Durham is located in a large, two-part building with a worn brick exterior; the “bunk” building hosts the beds for different individuals, while the other serves as the cafeteria, food bank and other amenities. Between the two buildings is a large, black iron gate with the organization’s title written in bold metal letters. The gate encloses a courtyard area, and on nice spring days the fence is surrounded by people sitting in the sun. The street corner where the shelter sits is spotted with individual residents sitting aimlessly either alone or in groups of three and four.

Inside the administrative part of the building, the atmosphere is cheerful and welcoming. There are big windows at the entrance, allowing the natural light to highlight the cream walls and linoleum floor. Almost every person in and around the building—staff and residents alike—is friendly and quick to say hello, despite the challenges that have brought many of them there.

Urban Ministries originally only served men, but has since responded to the rising needs of women and families. It currently has 81 available beds for men, 30 for women and nine family rooms, reaching 149 beds in total. The agency offers three meals a day to its residents and hosts a food pantry and clothing closet for the public, as well. UMD offers both emergency care and transitional assistance. Emergency care entails providing anyone in need a bed on a given night—space providing—regardless of their circumstance or likelihood of escaping homelessness. The organization provides this care to anyone for 60 days during the year but requires that they join a program if they plan to exceed that timeframe. The shelter’s Journey Program helps homeless people transition into permanent housing. It reaches out to residents who fall into a variety of categories, including medical and mental health assistance, veteran care and substance abuse recovery.

Residential Program Director Alex Herring, who joined UMD earlier this year, has taken on the difficulties involved in offering both emergency and transitional care because of the high demand for both services. Herring, a middle-aged black man with a pastor-like, slow voice, has worked in human services throughout most of his career. Before coming to UMD, he served as a full-time minister as well as a substance abuse counselor, a mentor for men exiting prison and a member of the Wake County Human Services Board. As a single father of two who has accumulated knowledge of homelessness and the barriers many face in exiting it, he said he has come to understand and treat the issue with a unique perspective.

“Many times we think homeless people don’t desire to work, that they have drug addictions and all these other issues, which some of them do. But it’s a very small percentage,” he said. “A lot of people who are homeless just ran into circumstances. The best way to describe it is just life. I think we have a clearer understanding with what we’ve seen in this country with the economy changing—we’ve seen now how real homelessness is for many people who were doing well and are now struggling…I think sometimes we look at homelessness as a state of being but I think it should be looked at as a transition.”

Just “running into life,” however, doesn’t mean that treating or eradicating the problem is easy. Though UMD aims to eliminate homelessness in Durham entirely, it’s unclear as to whether or not that is an attainable goal for the organization.

“[Ending homelessness] is such a major undertaking. There are so many aspects to homelessness that we still have not addressed,” Herring explained. “There are some people that go to work in the grass-roots level and I admire them a lot—they’re going out into the camps in the woods, they’re going under the bridges, they’re going to abandoned buildings, and they are finding people that have been forgotten about. How many people think when they drive over a bridge that there’s probably someone sleeping there? Most people don’t know, but there are a large number of people who sleep at these camps, or under the ramps that you use to get onto the freeway. So I don’t know if we can wipe it out [just through UMD], but I think that we put forth a good effort to try to address the issue.”

The Genesis Home, where Ryan Ferhman works, has a different approach to serving its residents. It works specifically with families—defined as one or more adults with custody of at least one child—in transitioning into permanent housing. The Genesis Home hosts a maximum of 15 families at a time, and requires a structured application process before granting access to the facility. The shelter is unique in that its residents usually stay for much longer than those in other agencies, at an average length of two years.

Resembling a large, three-story house with a playground in its backyard, the Genesis Home is located two blocks away from Urban Ministries. And unlike UMD, which is usually surrounded by its residents for the majority of the day, Genesis Home is a hubbub of activity during morning and nights but is quiet for most of the daytime. The home provides case managers that work with each family to set specific goals regarding their “graduation” and assist parents with initial employment challenges such as structuring a resume, finding job leads, and getting referrals to other services they may need for mental health or employment training. After that, however, the shelter leaves much of the responsibility to the family to make changes in their situations.

“We have a requirement that folks either do go back to school or work full time, so usually in the morning the school buses are here and the parents are seeing their kids get on the bus and then they head to school or go to their job,” Ferhman said. “Usually our parents are getting back here at around 3:30 or 4, because that’s when the buses are getting back. Then usually the kitchen gets kind of loud; just about every family in our house gets food stamps so they do their grocery shopping and cook their own food. We have a communal kitchen, but every family has their own room. When a family is ready for their own quiet time, they can go in and lock their door and watch a movie, or read or do whatever.”

Though the Genesis Home welcomes any type of family that meets its requirements, Ferhman said the most common familial structure they see is that of single mothers with children. Single parenting is highly correlated with poverty and homelessness, he explained, because of the high fair-market rents in the city and the challenges single mothers face to balance work hours and parenting.

Durham’s Plan

Like Herring, Ferhman emphasized that the shelters have been effective in graduating their residents, though homelessness will not be eradicated without government support. In 2006, Durham established its Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness, which aims to eliminate homelessness by 2016. To accomplish this, the plan called for increased collaboration with mainstream poverty programs and “enabling homeless people to access permanent housing more quickly by increasing the supply of affordable housing and permanent supportive housing, ensuring that people have incomes adequate to pay for basic needs, and providing appropriate services for those who need them,” according to the plan’s website.

Stephen Hopkins, a former candidate for Durham County Commissioner and a member of the Homeless Services Advisory Committee—a group designed to oversee services provided for the homeless population, including the recent plan—said that Durham still has a long way to go before it accomplishes its goals. Hopkins, an older black man with a sharp tone and nearly-toothless grin, said he has an insight into the issue that most committee members do not; Hopkins is an ex-offender with a history of drug abuse and was homeless for a portion of his life. He said that the only way for the plan to be effective is it if is more closely monitored, sets more measurable goals and is run by people who understand the problem.

“The people that are making the decisions have never been in those [homeless] situations, so they don’t know what to do about it,” Hopkins said. “And they’re not listening to the folks who are in that situation, they think that [the homeless] don’t know what their own needs are. It’s not true, but that’s what they think.” Hopkins said the committee he sits on has yet to make a strong impact on the problem because it is newly-formed and still assessing exactly what needs to be done. Ferhman said that without better organization and established goals from HSAC, the city can do little to succeed in its venture.

“The reality is… we need to get the Homeless Service Advisory Committee out of the weeds of who-does-what, and actually doing things that help homeless people because they have not done that, up until now,” Ferhman said, adding that he anticipates seeing what is in the committee’s future. “This work is so hard on a day-to-day level, at the agency level, that you’ve got to have the folks—the higher-ups, the city county folks, the ones that are on this advisory committee—they’ve got to help direct traffic and really address those barriers in a way that helps the agencies. And that hasn’t happened.”

Though there may not be a clear end in sight for homelessness in Durham, Herring said he is encouraged by the steps Durham is taking toward improving the situation.

“I think Durham has taken a very proactive role in dealing with this issue. They’re recognizing that there is a problem…They’re sitting down and talking. They’re allocating funding for specific purposes for getting folks back into housing or getting transitioned into permanent housing. They are looking at the issue that often times people can come to UMD, however there needs to be some aftercare,” he said, which is a positive step for the county.

As to whether or not he thinks the situation can be resolved entirely, Herring remains unsure. He does have a strong opinion about one thing, however. “As long as I stay in this position and work with this problem, I do see a brighter future,” he said. “I’m going to put forth every effort, I’m going to beat every bush, I’m going to knock on every door that I can find to ask people to help.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.