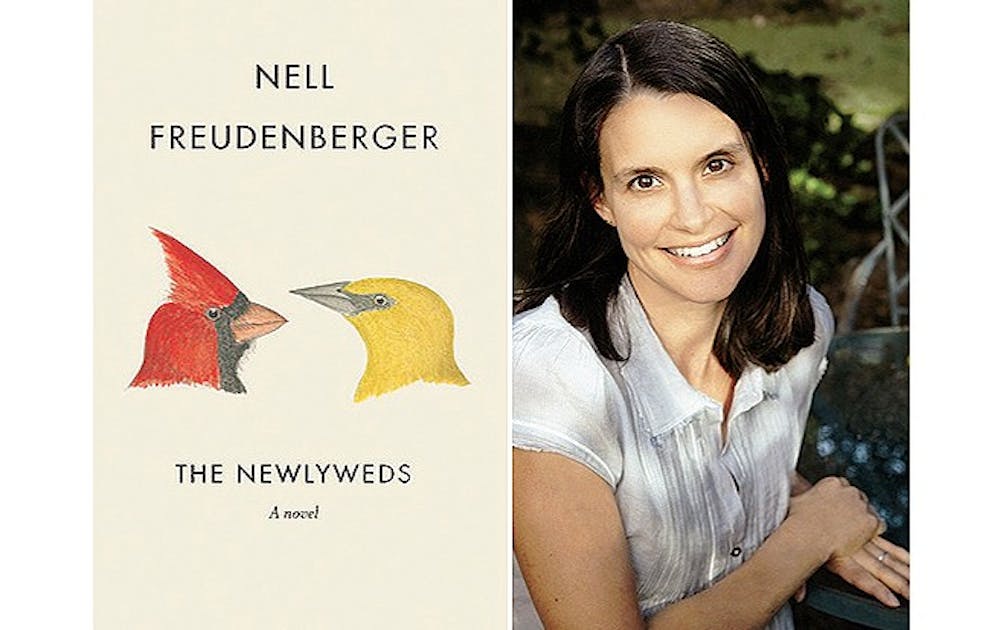

At one point in Nell Freudenberger’s novel The Newlyweds, Amina, a newly-married Bangladeshi woman living in America with her husband George, explicitly reflects on the unique circumstances of a cross-cultural relationship: “She and George didn’t disagree very often, but when they did it was always because of ‘cultural differences’—a phrase so useful in forestalling arguments that she felt sorry for those couples who couldn’t employ it.” But the cultural differences that Amina faces are only the superficial problems of the complex story that unravels. At the heart of The Newlyweds, there exists the culture-blind problem of the past—are our past selves worth reconciling with the present version for a more complete life? Or are they merely former incarnations forever threatening to sabotage who we want to be?

Freudenberger magnifies the impact of the characters’ pasts by first setting up an uncertain future. By titling the first section of novel “An Arranged Marriage,” she is already addressing the unique circumstances under which Amina and George met and the perceived connotations. Finding each other through the pointedly-named online dating website AsianEuro.com, Amina and George begin their courtship in a way that, to many, seems insincere or destined for failure. But Amina and George’s relationship is not governed by the typical power dynamics of an arranged marriage, nor does Freudenberger pity Amina or vilify George. Instead, she hones in on Amina’s splintering persona, and it is Amina herself who drives the distinction, categorizing her thoughts and actions into “Desh Amina” and “American Amina.” With the hopes of bringing her parents over to America to live together (a custom that George finds foreign and intrusive) Amina is inevitably stretched across the Pacific Ocean, with one half trying to adjust to her new (better?) life in America and the other grasping for her family and the familiar.

As the plot develops, the conflict shifts from that of the bickering newlyweds to Amina’s strained loyalties to her family and George. Admittedly, this is where Freudenberger begins to falter. After she leaves the first section of the book—a territory where she skillfully avoids banality when describing Amina’s job at a media conglomerate, her confusion about “Plan B”, and her newfound love of the snooze button—she begins a to weave a more complicated family melodrama alongside the main plot. Freudenberger’s detailed description of Amina’s family history, which unravels after Amina travels to Bangladesh in an attempt to bring her parents to the US, slips into a clunky, confusing tale that weighs down the domestic center of the novel. While some authors, like Gabriel Garcia Márquez, shine in their ability to effortlessly present a tale of vast scope, Freudenberger seems more suited exploring the intricacies of a microcosm. Throughout the second half of the novel, I kept waiting for the plot to unite George and Amina so I could read more about Amina’s two-fold transformation from single woman to newlywed as well as Bangladeshi daughter to American housewife. So it was only fitting then, that when Freudenberger was featured in The New Yorker’s 20 Under 40 Fiction Issue, it was alongside an excerpt from “An Arranged Marriage,” the first section of the novel.

The noticeable falloff in inspiration all makes sense with a little bit of backstory. In the “Acknowledgements” section at the end of the novel, Freudenberger thanks Farah Deeba Munni, a woman whom she met on an airplane six years ago who inspired the book’s premise with her double life and memories. With an incredible story waiting to be fictionalized, Freudenberger wrote The Newlyweds, a novel whose composition mirrors its title—an initial honeymoon period that drifts into something a little less sweet by the end.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.