Over the weekend, I voluntarily neglected the roughly Siberia-sized number of obligations I had for this week and chose to watch the Oscars. I produced only a handful of genuine, if trite, reflections: I like Jessica Chastain’s dress; Meryl Streep and Christopher Plummer are total dreamboats; I should stop pretending I don’t like Woody Allen, etc. One moment, however, led me to a level of excitement and anxiety similar to when I stopped caring about all the plotlines on Downton Abbey except for those involving Sybil and Branson. Pina, an unexpected, gorgeous, quirky art film/documentary about the German choreographer Pina Bausch, was pitted against, among others, the documentary with a suspiciously-familiar-uplifting-sports-team-narrative called, prosaically, Undefeated. And Pina lost.

I haven’t seen Undefeated, nor do I want to reduce this into a diatribe positioning the arts against athletics (mostly because it’s an argument I don’t really believe in). After viewing Pina twice (once in 2D and later in 3D) I simply want to make the case that this film—which I fear much of the population may write off because it has to do with That One Art Form That Scares Almost Everybody, Dance—is relevant, necessary and, perhaps most importantly for cinematic audiences and culture-fiends alike, entertaining.

Wim Wenders, the German film director known for films like Paris, Texas and Buena Vista Social Club, began the documentary project in 2009 but cancelled production after Bausch died at 68, five days after receiving a cancer diagnosis. Her dancers—who compose the Tanztheater Wuppertal, Bausch’s company grounded in dance-theater works informed by German expressionism and surrealism—convinced Wenders to finish the film as an elegy to Bausch.

More than a reflective exploration of some of Bausch’s most well-known works, Pina is an evocative testament to the idea of documenting dance and movement—practices that are, at their core, ephemeral. It seems eerie though somewhat fitting that Merce Cunningham, another dance stalwart and cultural innovator, passed away almost a month after Bausch, initiating controversy over his Legacy Plan to disband his company but preserve his archives.

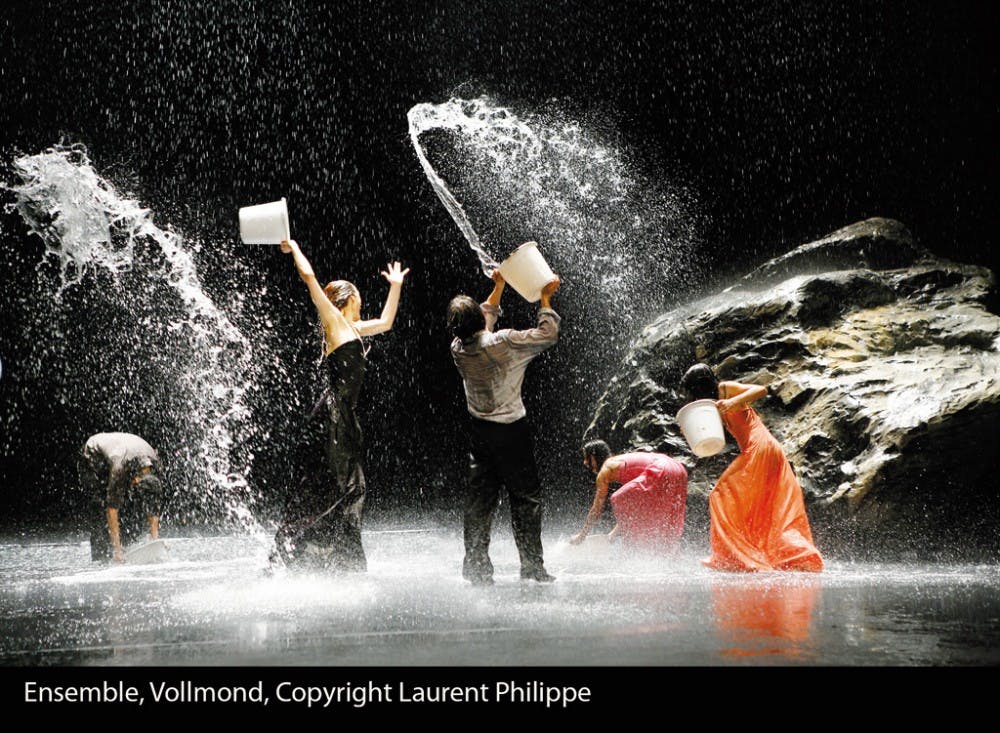

Wenders’ film, which alternates between footage of Bausch’s dancers in interview format and in her pieces (staged both inside a typical theater and outdoors around Wuppertal, Germany), engages the viewer in what feels like a living, breathing tribute to the creative potential of Bausch’s works. I admired Wenders’ commitment to showing long excerpts of the pieces rather than packing in an overabundance of flashy snapshots to appease the short attention span of 21st century viewers. Such a fragmented rendering would forego the sense of narrative and trajectory that Bausch’s pieces evoke. Wenders instead lets us mull around in the dirt-covered stage of The Rite of Spring, Bausch’s hostile interpretation of Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Diaghilev’s 1913 ballet collaboration, or Cafe Muller, an unsettling drama in an empty cafe in which women plod around, eyes closed, in white dresses while men manipulate the chairs, tables and eventually the women’s bodies in a series of frustrated, seemingly pointless embraces.

Gender is a key element in Bausch’s performative investigations of ritual and social behavior, though her statement isn’t so easy to tease out. In all of the pieces Wenders features, female dancers are clothed in evening gowns and male dancers in suits or business-casual attire. In a departure from the rest of their appearance, though, the women frequently abstain from wearing makeup and leave their hair loose, dominating the space with a femininity that, while powerful, is undefinable at best. The men, often sans-formal footwear, utilize stoic facial expressions to suggest both hyper-masculinity and bewildered impotence.

Even the film’s lighter moments hint at more serious undertones: one older male dancer dons an elaborate white tutu while repeatedly collapsing atop a moving trolley in an underground, graffitied tunnel; a figure in exaggerated cardboard bunny ears riding public transport is unfazed when a woman enters, making Transformers-esque noises while beating a pillow, her hair shrouding her face. In the interviews with the dancers, who interestingly sit speechless while their words are played over their tableaus, statements are thrown around that praise Bausch’s artistry and ability to, through performance, elevate the idea of being human through an incisive adaptation of the everyday.

Between these dialogic inserts and the film’s resplendent cinematography, Pina expertly mixes similar ideas of truth and fiction, spontaneity and prescription, the casual and the decadent. Many critics have praised Wenders’ use of 3D, citing Pina as the first satisfying 3D movie that uses the medium to the material’s advantage. I agree: the effect emphasizes the phantasmagorical effect of some of Bausch’s pieces, while at other times makes us feel like insiders who can almost touch the wavering stage curtain in front of us. And this, in my view, is Pina’s greatest achievement: it is a film that takes a potentially unfamiliar subject, fleshes it out truthfully and provocatively and encourages viewers to ascend to a different, higher level of artistic engagement.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.