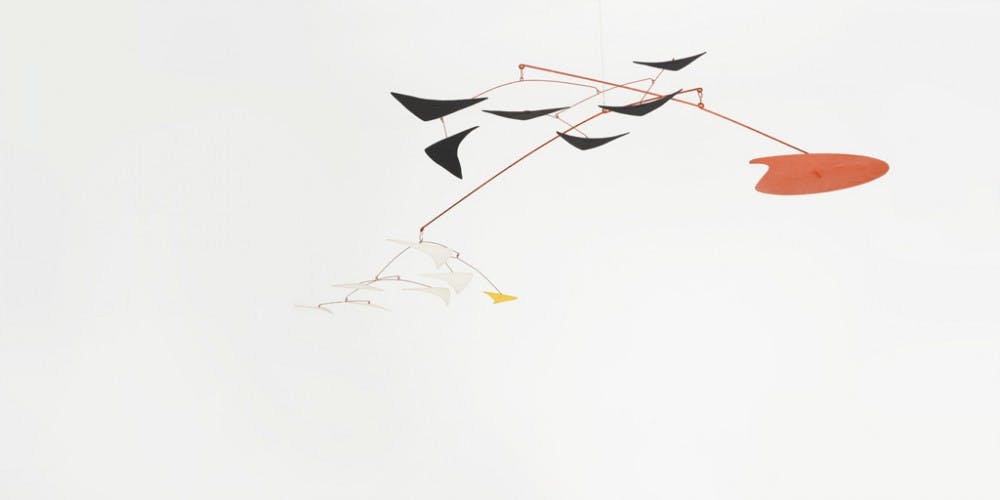

Alexander Calder’s is an art that speaks back, if you’re lucky enough to see it in person. If not by name, anyone who’s seen a hanging mobile knows Calder. Marcel Duchamp first used the term to designate Calder’s earliest hanging works of art, now an indelible form. But even more than ornaments spinning above a child’s cradle, Calder’s work is interactive at its best.

Beginning Thursday, a total of 32 Calder works will be showcased at the Nasher Museum of Art in Alexander Calder and Contemporary Art: Form, Balance, Joy, originally curated by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

“[It’s] like 360 different paintings; at every angle it changes,” said Wendy Hower Livingston, manager of marketing and communications for the Nasher.

It’s an apt declaration, especially for Calder’s pieces that look like 2-D forms fleshed-out into the living dimension. He was “really working with lines—the curve of lines in the air,” said Sarah Schroth, coordinating curator for the exhibition’s Nasher visit.

As Livingston reminded me, he was also working with a mechanical engineering degree. Calder’s capacity for building expertly weighted, delicately perched mobiles and sculpted forms remains remarkable. Resembling a futuristic floral bouquet, Orange Paddle under the Table exemplifies his knack for representing balance.

Seven other young artists’ works are displayed alongside Calder: Martin Boyce, Nathan Carter, Abraham Cruzvillegas, Aaron Curry, Kristi Lippire, Jason Meadows and Jason Middlebrook.

“You can see how the contemporary work is talking to the Calder,” Livingston said.

What the pieces by all artists have in common is an erection in space that seems to defy gravity—or rather, to acquire its own kind of gravity. Taken together, the interplay between the masterworks and its inspired offspring creates a futuristic playground forest—sans the dread “futurism” often invokes. Plumeau Sioux (Indian Feathers) teeters several feet overhead, evincing a child-size stairway to heaven.

A model of Middlebrooks’ From the Forest to the Mill to the Store to the Home to the Streets and Back Again balances a log against manufactured materials—and tells a tree of life story in a strikingly immediate way. Jason Meadows’ Pig Latin is 2-D form distended in the third dimension: a pig family distorted at severe angles, all very formal language, inappropriate to what is actually a fun piece.

But not all the artists create art as effortless as Calder’s; the point of their cohabitation in the exhibition was the “rethinking of an artist so familiar you don’t look at him anymore—to bring attention back [to Calder] in a new way.”

Form, Balance, Joy is otherworldly yet approachable. It beckons to its audience and at one point in the tour Livingston cautioned that I not bump into a black metal sculpted piece, Little Longnose, that was “reaching out” to me.

The interwoven geometric sculptures by Curry are heavier, and a bit at odds with the zen harmony of Calder’s—works in this vein might elicit some eye squinting. But altogether the exhibition offers a refreshing collection of contemporary art mostly unburdened by cerebral concepts. It’s art in practice instead of theory, important as the latter is to the experience of exhibits like The Deconstructive Impulse. It’s better suited to ponderous circumambulating than scrutinizing the descriptive labels.

“The art is really striking. You walk by and immediately know it’s a Calder—the primary colors, the engineering, a really unique aesthetic and experience compared to paintings,” said Reshma Kalimi, co-chair of the Nasher Student Advisory Board, which planned a Hollywood-themed party to attract undergraduates to the museum this Friday.

Scroth reiterated that seeing the pieces assembled was a “revelation.” Watching the final exhibit erected in the Nasher’s Great Hall removed some of the allure—realizing that these works didn’t just fall into being, but are in fact products of intelligent design. Some of the most intelligent in contemporary art, at that.

Alexander Calder and Contemporary Art: Form, Balance, Joy runs until Jun. 17 at the Nasher Museum of Art.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.