Sharing data publicly is a practice that advances scientific discovery and benefits society at large, two leading geneticists said in a lecture Monday.

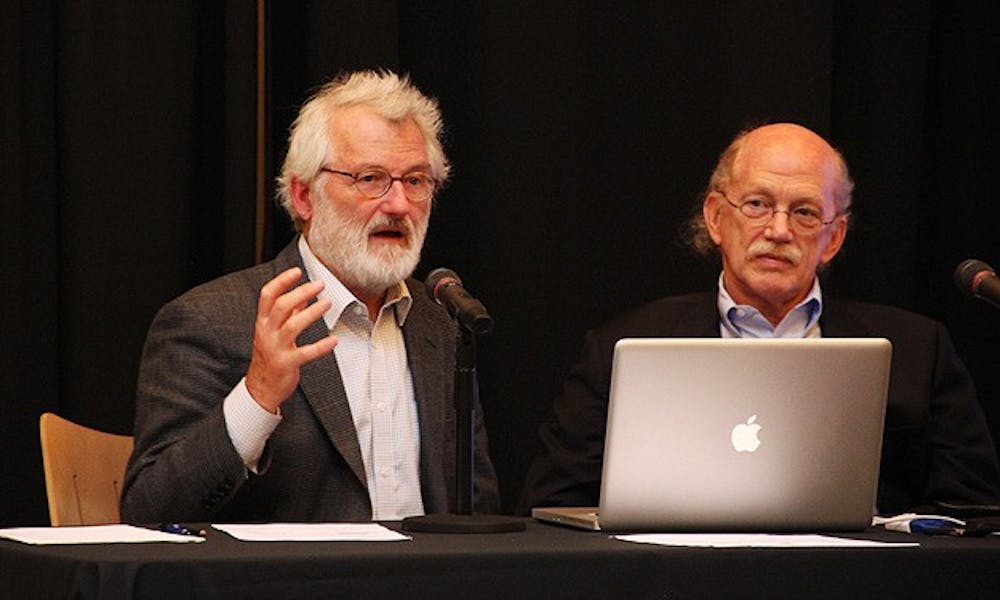

Nobel Prize winner Sir John Sulston and Dr. Robert Waterston delivered a lecture on the social value of science and the free spread of scientific data. Their talk, “The Common Wealth of Science,” was the James B. Wyngaarden Distinguished Lecture in Genome Sciences and Policy, sponsored by the Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy.

“Science works best when you are able to get the data out there and people are able to use it,” Sulston said.

Sulston and Waterston worked together to complete the first sequencing of a multicellular organism—their worm genome was published in December 1998. As director of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in England, Sulston led one of the four principal sequencing centers for the Human Genome Project, and Waterston researched human genome sequencing at his lab in St. Louis.

Sulston and Waterston also played instrumental roles in establishing the Bermuda Principles on data sharing, which advocate maintaining genome data in the public domain. This philosophy prevailed against those who argued for proprietary human genome databases, and it came to shape the proliferation of information on the human genome.

“The Human Genome Project is a resource-intensive project that is meant for the public—the data is released so the utility can be maximized,” Waterston said.

IGSP Director Dr. Robert Cook-Deegan noted the significance of this approach for students of genomics.

“[I want them to] learn about not just the Human Genome Project but also the way it came into being—lots of databases and open information, and to have students think about optimal ways of doing science,” Cook-Deegan said. “It was a fateful choice—what Sulston and Waterston made.”

Public central data is crucial to scientific advance, Sulston said, adding that it is necessary to find the right balance between the public and private domains. The fact that an increasing amount of scientific discoveries rely upon market systems, however, prioritizes commercial rather than social benefits.

“There are marketing excesses that distort the transparent process in scientific discovery,” Sulston said.

Sulston also noted conflicts between producing the best medicines and the most profitable ones and said for-profit medicine limited the possibilities of eliminating diseases such as HIV and tropical diseases in poor countries.

“Doing lots of sciences is not enough—we have to think about what the balances between [social benefits and business profits are] and where we are going,” Sulston added.

Lauren Dame, associate director for genome ethics, law and policy, noted the role that intellectual property plays in the development of research.

“We are interested in how intellectual property can help and hinder science,” Dame said. “As key figures in the Human Genome Project, they are instrumental in promoting an open norm.”

Sulston also outlined the policy-level process of scientific discovery. From discovery to knowledge to understanding, what is being investigated goes into the stage of application, which facilitates new discoveries, he said. In particular, Sulston noted the relationship between science and culture.

“Science is the major cultural drive for the past hundred years,” Sulston said.

Freshman Hillary Bowman said she is concerned about the lack of transparent information, confirming the speakers’ contributions made to science and society.

“What would have happened if we had not implemented the public databases?” Bowman said. “I can hardly imagine the consequences.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.