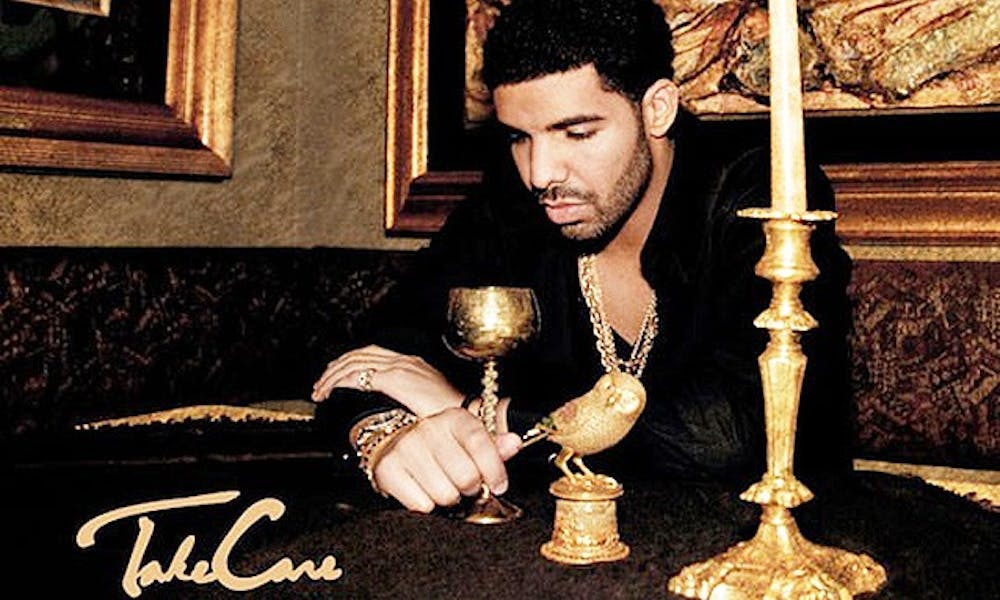

For whatever else it may be, Take Care is most of all a contrivance. It’s a remarkably representative reflection, at one particular moment in the man’s contrived second career, of an Aubrey Drake Graham of Toronto, Ontario, who once starred in a teen soap opera called Degrassi: The Next Generation.

All of this is more by way of description than evaluation; that is, leave aside for now any of the pejorative notions implicit therein. Two of Drake’s Take Care collaborators, Rick Ross and the Weeknd, have conjured up similarly contrived on-record personas to impressive results; that Graham once starred in a teen soap should be no more an indictment than, for instance, that William Leonard Roberts once worked as a correctional officer or that Abel Tesfaye’s misogynistic anecdotes are most likely fictional constructions. Outsized personalities, regardless of their basis in reality, can make for good rap music. Nahmean?

Drake had this last point already figured out on 2010’s Thank Me Later. That album was unabashedly self-centered, and the Drake at the center wasn’t afraid to show off a loverboy croon or to represent himself as the king of a game he had barely started playing: being a rapper. Eighteen months and a slew of high-profile guest spots later, Take Care improves on its predecessor’s attempt to define the patently absurd creation that is Drake. This means synthesizing a set of disparate strands—world-beating swagger, Southern-rap signifiers, Noah “40” Shebib’s synth-heavy atmospherics, not to mention a whole bunch of loverboy crooning—into a coherent whole. If that sounds like a task, well, it is.

“Marvins Room” succeeds for the same reason that “Runaway” and “Blame Game” worked on Kanye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy: each demonstrates its creator’s vulnerability by struggling against it. The repeated female vocal, “Are you drunk right now?” that anchors the track reminds us that we’re listening to a guy who, despite enjoying all the fame in the world, can be chillingly empathetic: sad, impulsive, unsure of whether to be regretful or vindictive, ultimately coming off as both at once. By contrast, “Shot for Me” and “Doing it Wrong” simply dress up unlikable misogyny as false sympathy; “Practice” is too sincere in its delusion to come off as anything other than creepy, much less relatable.

Of course, this is but one of many sides of Take Care. The union between Drake and Lil Wayne’s Young Money label is the most incongruous in rap today, and absurdist shit talk via Lex Luger bombast of the former has rubbed off on Drake’s tortured superstar confessionals, mostly superficially. His verses on “Headlines” and Tha Carter IV’s “I’m Good,” which took shots at West and Jay-Z, have attracted plenty of scorn from traditionalist rap blogs quick to point out that, hey, this is Wheelchair Jimmy speaking. That’s not in and of itself a substantive criticism. When taken alongside Drake’s penchant for reconnecting with exes and wooing strippers, though, his poorly-executed newfound aggression makes Drizzy look all the softer. Likewise all his lip service to chopped-and-screwed Houston trap-hop: there’s a track here called “Underground Kings,” and on “Good Ones Go,” he raps, “I’ve been chilling in the city where the money’s thrown high and the girls get down/ In case you’re starting to wonder why my new shit’s sounding so H-town.” It doesn’t, not in the least, and the lyric exemplifies the sort of self-aware artifice that can make Drake so repellent.

Appropriately, what’s most striking about Take Care is its unrepentant ambition. Take Care comes closer to the superhuman, epochal designs of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy than anything since, and Kanye West’s magnum opus provides an illuminating comparison. “Marvins Room” isn’t as grandiose in its execution as “Runaway,” but both tracks demonstrate Drake and West, respectively, at their most vulnerable and most incisive; Kendrick Lamar even shows up to play the Pusha T-esque foil on the subsequent interlude “Buried Alive.” Like “Lost in the World,” Take Care’s title track features a Gil Scott Heron sample and a piano riff over a four-four beat. And both albums are consumed by women, and their creators’ tumultuous relationships with them.

Take Care doesn’t stand up to MBDTF, though even mentioning the two together certainly confers some measure of merit on the former. At eighteen tracks, Take Care appears bloated next to the fiercely purposeful MBDTF, and Drake doesn’t exhibit West’s talent for sequencing his songs to maximum effect. Most crucially, and most revealingly, though, is this: even relative to Kanye’s torturous complexity, Drake is shooting for something too multifarious and, again, contrived, to ever really hit his mark.

That’s a shame, too, because aside from the posturing, Drake’s flexing an undeniably impressive flow on Take Care—rhythmic and economical, composed but aggressive, squeezing punch lines into the last possible syllable without ever seeming out of breath. Sure, there’s the ill-advised Nicki Minaj affect he tries on “Make Me Proud,” and his scratchy monotone on “Cameras” is modeled after Weezy but winds up sounding more like Kid Cudi. But tracks like “We’ll Be Fine” and “Underground Kings” don’t just mark development from Thank Me Later; they show a rapper who’s found a voice worthy of his boasts.

—Ross Green

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.