In the entrance to the new exhibit at the Nasher Museum of Art, Becoming: Photographs from the Wedge Collection, a giant paragraph on the wall defines its purpose: “[to] reject the common tendency to view black communities in terms of conflict or stereotypes.”

By this measure, Becoming is a certain triumph. Chronicling 120 years of portraiture, the exhibit presents a beautiful and fiercely authentic narrative of black agency.

The works come from the collection of Dr. Kenneth Montague of Toronto. Montague is originally from Windsor, Ontario—a town separated from Detroit by a border and a sliver of Great Lakes water—and grew up in the 1960s and ’70s, a contentious period for people of color.

After completing dental school in 1987 (he now cares for the teeth of celebrities Russell Crowe and Nelly Furtado), Montague began collecting photography in earnest. He opened a small gallery in 1997, displaying pieces in the narrow “wedge” hallways in his loft apartment. Its success soon led to the Wedge Curatorial Project, a nonprofit that raises public awareness of the arts, particularly art from the African-Canadian diaspora with which Montague identifies.

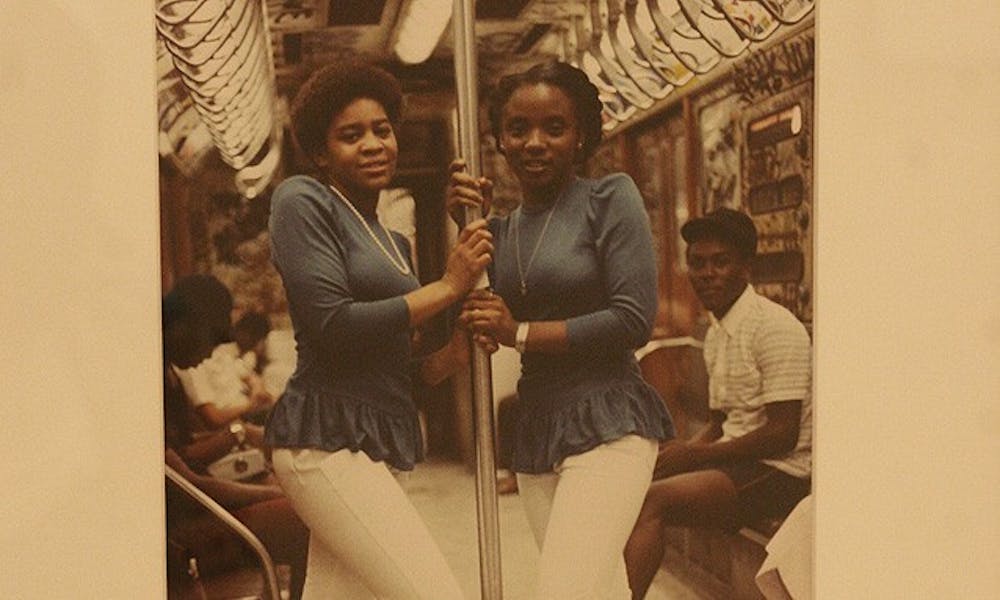

The photographs capture the African diaspora at dozens of culturally significant moments; European, African and North American artists comprise the majority of the work. An 1891 print of Jamaican women harvesting sugar cane evokes the pre-industrial Caribbean. Further along chronologically is James VanDerZee’s classic image of Harlem’s Jazz Age opulence in “Couple in Raccoon Coats.” Wonderful portraits by Jamel Shabazz depict the infancy of hip-hop culture in 1980s New York.

A theme of Becoming is the rising economic might of North American blacks. Fred Herzog’s 1959 candid of a stylish black family walking a spaniel down the streets of Vancouver in a scene that evokes American normalcy à la Norman Rockwell. As does Henry Clay Anderson’s portrait of a happy couple straddling a motorcycle in Greenville, Mississippi, home to a burgeoning black middle class from the 1930s to the 1970s.

Becoming is refreshing for what it tacitly omits: representations of blatant racial conflict. Absent are images of colonial oppression, violent revolution or civil rights clashes. Political icons like Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X or Nelson Mandela are missing, too. As a curator, Montague seems more interested in the lives of “regular” blacks, affording them an individuality that might be overlooked in conventional narratives of cultural warfare.

The exhibit makes sure each viewer is painstakingly aware of the history of unbalanced power relations between whites and blacks. The images of Becoming do not suggest a 20th century free of racial trauma, but rather focus instead on the black identity that flowered indefatigably, against the odds.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.