Scholarly research is being questioned at unprecedented levels, due to increasingly critical review processes and recent, high-profile retractions.

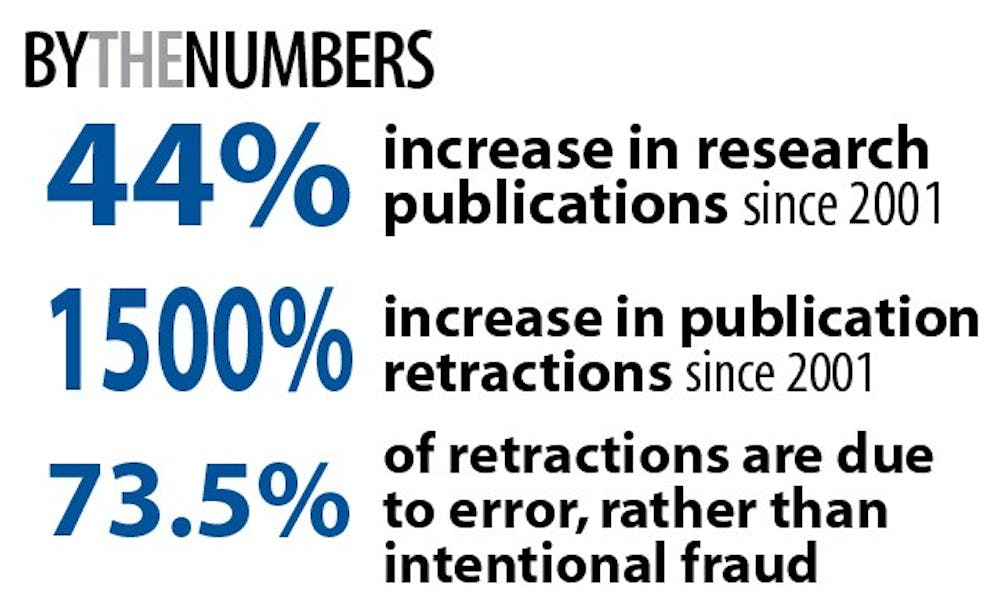

During the last 10 years, the number of papers published in research journals has risen 44 percent, but the number of papers retracted has skyrocketed by more than 15 times, according to a recent story published by The Wall Street Journal.

“The article says that the core basis of science is trust,” said Tom Katsouleas, dean of the Pratt School of Engineering. “I would say that trust is an important piece, but the first thing is reproducibility.... Gradually, the scientific truth comes out.”

He added that retractions are the result of a more thorough review process as well as scientists replicating experiments in order to test and possibly invalidate published data.

“More people are looking at other people’s work, so things are coming through the surface more often,” said Dr. Robert Califf, vice chancellor for clinical research and director of the Duke Translational Medicine Institute. “I don’t think it’s that people have gotten more dishonest.”

More highly publicized retractions have shed light on questionable research and led reviewers to implement more stringent policies to address fraud, said George Truskey, senior associate dean for research in Pratt and director of undergraduate studies in the Department of Biomedical Engineering. Truskey was also named chair of the department Aug. 10.

“Twenty-five years ago, a scientist would probably dismiss [the idea of a retraction] and say ‘That’s impossible,’” he said. “But we’ve learned that it’s not impossible.”

It is mostly incorrect data that accounts for the surge in the number of retractions—73.5 percent of the retracted papers were due to incorrect data and only 26.6 percent were a result fraudulent—or falsified—data.

The high percentage of errors may be due to increasingly complicated data, Califf said, noting that small errors in computer programs can yield significant errors in the data.

And though the number of retractions in the scientific community has increased overall, the number of retractions is still relatively low in comparison to the number of studies published. According to the study, among the 11,600 peer-reviewed journals considered in the study, 22 retractions occurred in 2001, 139 in 2006 and 339 last year.

In the social sciences, errors often occur when models are incomplete or exclude important variables, Dean of the Social Sciences Angela O’Rand said.

Since studies in the social sciences and humanities are often more difficult to replicate and less precise, retractions are less common, O’Rand noted.

“If an article is published and makes a mistake, or the model wasn’t good, often the journal publishes the criticism,” she said. “The response becomes a public discourse debate, and the response isn’t so clear cut.”

Damaging data

False data can be severely damaging if it is not invalidated immediately.

“It’s not just an issue of ethical behavior,” Truskey said. “In the biomedical area, work can have significant consequences on health, and there have been some cases where that has happened.”

Following the retractions of two papers by Dr. Anil Potti, a former Duke cancer researcher, a N.C. law firm began investigating whether the research led to faulty treatment methods for patients, The Chronicle reported in February.

Although Califf said the Duke School of Medicine has had some retractions in the past, on average there are zero retractions per year at the school, Califf said, though he added that the past year was an obvious exception.

“We’re amidst one of the biggest retractions in medical history,” Califf said. “[Anil Potti] was a co-author on about 40 papers that had original data that was generated at Duke, and we’re in the process of retracting about a third of those papers, and there are another third... being partially retracted.”

Pressure to publish

Researchers often face pressure to publish papers from their superiors, community, peers and their own expectations.

Recruited faculty are expected to teach, research and be leaders in the field, Truskey said.

The social sciences emphasize the quality of research produced more than the quantity of papers published, O’ Rand noted.

“The pressures at a place like Duke aren’t just to do research and publish, but to publish in high-level journals or to publish books that are highly regarded,” she explained. “To get more funding, you have to publish.”

Everyone with a teaching title within Pratt is required to conduct research, Katsouleas said, adding that on average, Pratt faculty members each receive about $615,032 per year in grant research funding.

Research is not only part of a professor’s job description but also a key component when determining promotion, he said.

“One of the pressures is not from the institution but internally from competitive researchers is the desire to be first,” Katsouleas said. “That creates a tension between being first and being right, and unfortunately, sometimes the core values get corrupted, and it becomes more important to be first than to be right.”

The “publish or perish” saying, however, is an inappropriate depiction of the Pratt research environment, he added.

“Faculty here at this level are so intent on making the discovery and competing with their peers to be the group that makes the discoveries that you don’t even think about publishing,” Katsouleas said. “You just think about doing the research, and the publishing is sort of the last step in the process.”

More papers are being published due to other factors as well, including greater funding for research and an increase in collaboration among researchers, which lessens an individual’s workload, he added.

Preventing errors and fraud

Leading administrators in Pratt and the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences said they do not even remember a Duke study that has been retracted, with the exception of the Potti papers.

If a study were to be retracted, however, administrators said repercussions for the researcher would depend on whether the retraction was due to error or fraud.

“If [an article] was [published] early on in the field, someone would probably retract that article and not be particularly judged because of it,” Katsouleas said. “But in cases where they should have known or should have been more careful, then the scientific community would pass judgment and their reputation would be damaged—I think the worst penalty is the damage of reputation.”

Katsouleas added that a pattern of incorrect data leading to retracted papers could potentially affect a professor’s chance for promotion. The appointment committee considering promotion would seriously consider the retraction in the decision process, he said, adding that he has never seen a retraction since he came to Pratt.

Fraudulent data is a more serious—and more difficult to prove—offense, Califf said.

“In general, if it’s proven that you’ve committed fraud on scientific data, that’s grounds for dismissal in almost anybody’s book,” he said. “But proving fraud is a hard thing to do.”

Producing fraudulent data is not only considered an academic misconduct, but it is also illegal if the research is being funded by grants or other outside resources, Califf added.

“Fraud is a serious problem and one that we all have to watch out for,” he said. “It’s an unfortunate situation, and it’s also one that takes a while to correct itself. It’s something we need to pay attention to.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.