Lost and found isn’t so straightforward anymore.

Anxiety and high-pressure environments specifically hinder one’s ability to find a second item in a dual-target visual search, according to a recent Duke study published in Psychological Science June 13. This research has drawn the attention of the Department of Homeland Security, which has requested that the researchers look at how anxiety affects baggage screeners in security checkpoints at the Raleigh-Durham International Airport.

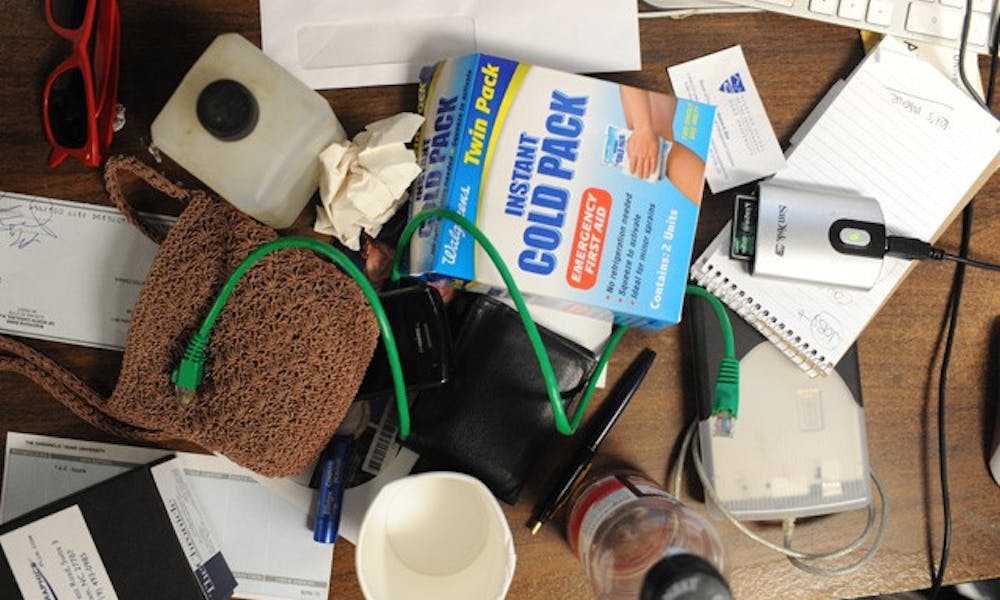

A visual search is defined as the process of using one’s vision to look for an object, such as a pen on a desk or a weapon in a baggage screening, said Matthew Cain, a postdoctoral fellow in cognitive neuroscience and a researcher in this study.

“The most exciting thing to me scientifically was seeing how we could affect performance simply by changing someone’s anxiety level,” Cain said. “We could change someone’s performance in a task just by making a suggestion to them, and that was enough to have people perform differently on what were otherwise identical conditions.”

Scientists had previously known about the “satisfaction of search” phenomenon, Cain said. This idea refers to how finding a second target is more difficult after successfully locating a first target. For instance, if a dentist were to find a cavity in an X-ray, he may be less likely to find additional cavities in the same X-ray.

To show how anxiety partially explains this phenomenon, the researchers built a computer display where subjects were told to identify the T’s among a large group of L’s. Twelve subjects were tested 28 times each, 14 in a control condition and 14 in a variable condition. The subjects were told that they might receive an electric shock when under the variable condition and hear a noninvasive tone under the controlled condition.

Under the threat of an electric shock, subjects typically showed more sweating and an increased heart rate, said Joseph Dunsmoor, a graduate student in psychology and neuroscience who worked on this study. He added that the threat occupies the subject’s mind, which causes anxiety levels to rise in response.

“We’re academics, and one of the primary goals is to study the mechanisms that [explain] how humans operate in our world,” said Stephen Mitroff, an assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience who led the research. “Visual search is something we all do constantly—we’re not all looking for tumors and X-rays, but we’re often doing things where it’s quite important [to find] what we’re looking for.”

One such area of importance is national security. The team of scientists will work with the Army Research Office, the Department of Homeland Security and RDU to further test the detrimental effects of stressful conditions on important situations that rely on accurate visual searches, Cain said. The team will soon set up computers at RDU to test the effects of anxiety on baggage screeners’ abilities to find dangerous items in security checks.

“For the [Transportation Security Administration], we’ll hopefully be working directly with baggage screeners this summer at RDU, and that was initiated by the bomb assessment officers at the airport,” Cain said. “They had seen some of our work previously and said, ‘Hey, we should talk.’”

It is still unclear, however, why anxiety hinders search success in general and also why people have so much trouble finding a second item but not the first.

“The next step is to kind of follow up on why people are impaired at finding multiple targets under anxiety,” Dunsmoor said. “[We’ll look at] what exactly is causing those mistakes [and] if maybe you could in some way remedy them.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.