March Madness is over without incident, but according to recent studies the threat of sudden death in athletes due to cardiac arrest remains too high for comfort.

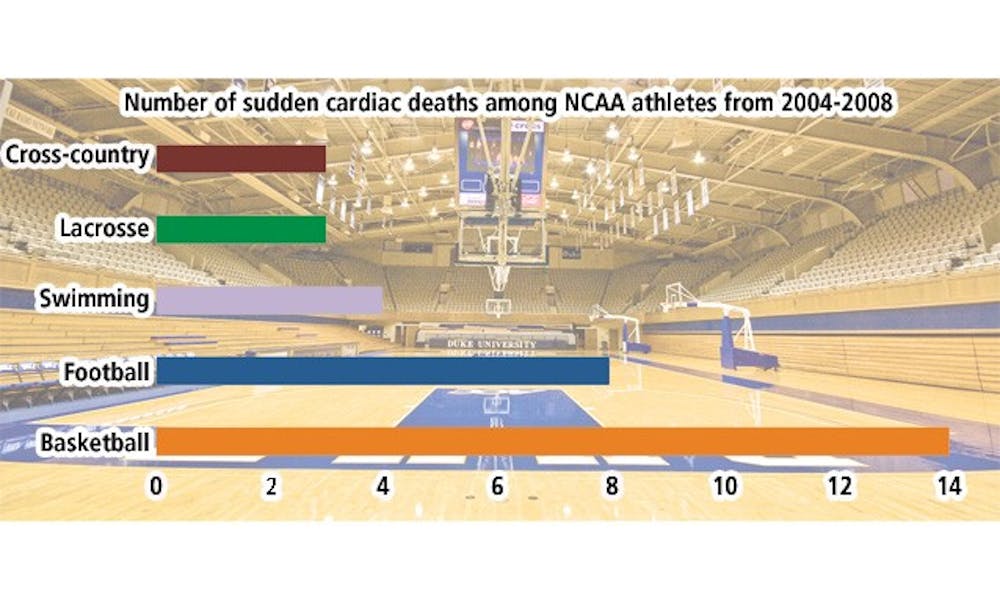

A study released April 4 from the American Heart Association found the rate of sudden cardiac death in NCAA athletes is one in 44,000 a year, with basketball players at the highest risk. The research was spurred by several incidents early this year in which high school athletes’ hearts stopped during athletic events. The tragedies have spurred cardiologists at Duke and other universities to search for reasons why apparently healthy athletes are suffering from these attacks and to find ways to prevent them.

Dr. Thomas Bashore, cardiologist and Duke professor of medicine, and said electrocardiographs—which measure the heart’s electrical activity—could help detect abnormalities that could lead to sudden death when athletes exert themselves.

“An ECG helps pick up those [individuals] with a congenital long QT syndrome and those with a lot of premature beats,” he said. “I think athletes [are required to] get an ECG in Italy, but [they are not] in this country because of the potential costs.”

When athletes die due to a stopped heart, it is often sudden and unexpected, as in the case of Michigan high school junior Wes Leonard who collapsed in early March after scoring a game-winning shot during a basketball game. The audience’s cheers after the win quickly gave way to panic as the 16-year-old became unresponsive and fell to the floor. He was later pronounced dead at the hospital.

Despite the risks, many athletes with undetected heart problems continue playing sports until they suffer cardiac arrest. They are often unaware of the increased danger of heavy physical activity because many routine physicals are unable to detect the underlying problems that cause cardiac arrest. Abnormalities are also subtle and difficult to detect, Bashore said.

“The most common underlying problem with the athlete who has sudden death during exertion is... a profound thickening of the heart muscle,” he said.

Bashore said he does not know how the Athletics Department screens athletes for heart problems.

“I would guess that Duke does an ECG and probably an echocardiogram on their athletes, but I actually do not know that,” he said. “I suspect they use someone in sports medicine or the undergrad clinic to do their screening.”

Several members of the Athletics Department did not respond to requests for comment.

Sophomore Georgie Kerber, who played football last year, said the University did routine physicals to ensure football players were healthy when he was on the team.

“I know we definitely had to do a physical where they checked our hearts,” he said. “I know that they monitor us pretty closely every day [and] everyone always has to go check in with [football Director of Athletic Training Hap Zarzour]... to make sure that everything is physically okay.”

Kerber said he cannot remember whether or not Duke required players to have an ECG taken.

Sophomore Mary Nielsen, a member of the field hockey team, said she thinks the University takes adequate measures to screen its athletes.

“We get our blood pressure and pulse taken in physicals, then if you tell your trainer about your symptoms, you get ECGs, echocardiograms and stress tests,” she said. “My teammate actually got diagnosed with [a heart condition last week]... her heart would stop or beat excessively fast at random times. She can’t play again until a heart electrical specialist talks about potential surgery with her.”

Ultimately, no matter how often screening occurs, sudden cardiac death cannot be completely prevented, Bashore said. Athletes often subject their bodies to great amounts of physical stress, and much of this burden is placed on their hearts.

Although the thought of cardiac arrest is frightening, the heart is a persistent muscle, and the probability that it will stop beating is extremely small, he noted.

“The sudden death incidence is very low,” Bashore said. “[The reason they] quickly make the news [is] because it affects an apparently healthy young person.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.