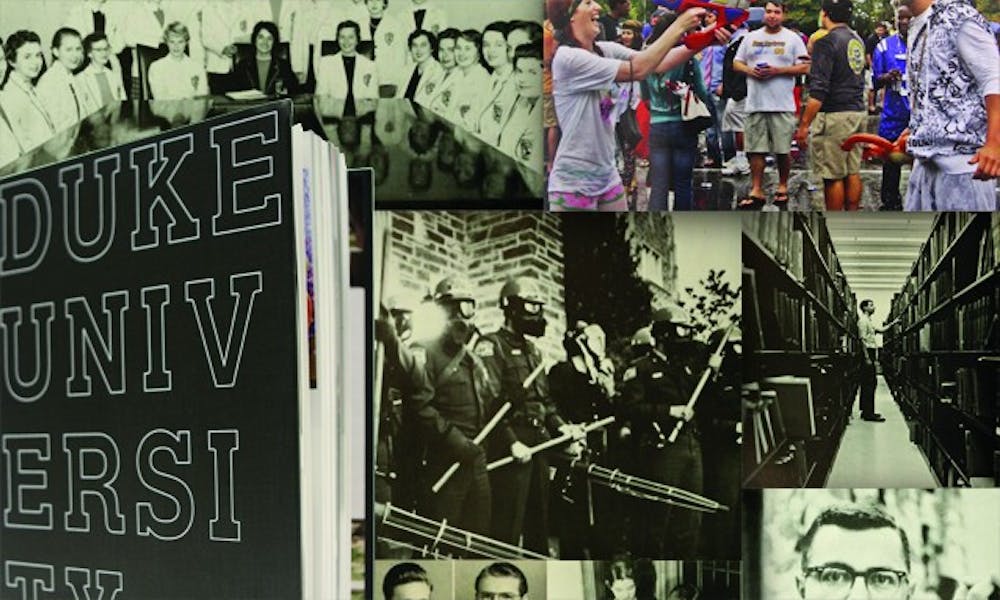

Before Elizabeth Dole was North Carolina’s first female senator, before she was a would-be first lady and, in fact, before she was even Elizabeth Dole, she was the president of the student government of Duke’s Women’s College. In the 1958 issue of The Chanticleer, the Duke yearbook, she sits front and center in the photograph of the Women’s Student Government Association Council, wearing a blazer and a single strand of pearls and flashing a toothy smile. Elsewhere in the book Dole, then Mary Elizabeth Hanford, folds her hands primly in her lap as she poses with her sorority Delta Delta Delta, sits robed in black with the rest of the women’s judicial board and finds herself scrunched between “Hanes, Elizabeth” and “Hankins, Robert” in the senior class portraits. And in every one of the photos, she’s wearing those same pearls.

Open a Chanticleer from 1969 and you’ll see plumes of tear gas rising from the Allen Building as police disperse student protestors who were demanding the establishment of an African-American studies department. In the 1955 edition, a lanky 21-year-old Reynolds Price pretends to ponder a submission to Duke’s undergraduate literary magazine, The Archive, of which he was then editor-in-chief. And in 1942, The Chanticleer published portraits of 12 men wearing sport coats and secretive half-smiles—members of the “Men’s Pan-Hellenic Council,” then the governing organization of Duke fraternities. Their yearly update announced, “The council continues to lead the social life of the University.”

But for The Chanticleer itself, the sailing hasn’t always been so smooth. When the yearbook turns 99 this spring, it will celebrate that anniversary by going before the Student Organization Finance Committee to try and defend a budget that’s been slashed nearly $50,000 in the past two years. Afterwards, its staff will return to an office stacked floor-to-ceiling with yearbooks from that same time period that they haven’t been able to give away—even with an unbeatable price tag (free). In an era of Facebook photos and digital cameras, when every student group has a website and every basketball game can be Tivo-ed into permanence, one of Duke’s oldest student organizations is staring down a life-or-death question: does anyone care about the yearbook anymore?

In the basement of the Bryan Center, scrunched between McDonalds and the Post Office, the Undergraduate Publications Board office is an inconspicuous presence on campus. Besides a row of Apple computers along one wall and a couple of couches huddled in the center of the room, most of the large space is taken up by magazines, literally thousands of them, slumping against each other on shelves, spilling out of boxes, leaning in piles against the wall. Literary magazines and photography publications, journals of science and public affairs and humor and dueling Democratic and Republican political tracts. The only other decorations are a few Post-it notes and some old cartoons hung on the walls.

You might not guess from looking at it, but the residents of this haphazardly organized office control nearly a quarter of the annual student activities budget, some $186,000 this year alone. (Full disclosure: two years ago I was the editor-in-chief of one of those UPB publications, The Archive.) That pays the bills for UPB to put out 15 student magazines—from the Journal of Prospective Healthcare to the travel publication Passport—and, of course, a yearbook, which accounts for almost half the total.

But from the looks of it, much of that money never makes it out of the office. In the smaller back room that serves as The Chanticleer’s stomping grounds, more than 2,500 copies of the 2009-10 yearbook, which arrived on campus in October, are still piled in boxes awaiting distribution. Per the group’s constitution—and the generous funding of Duke Student Government—the hefty books are free to any student who wants one. But that doesn’t mean it’s always easy to unload them.

“Most people don’t know we have a yearbook,” said junior Felicia Arriaga, the current Chanticleer editor-in-chief. “It’s kind of a shock to them.”

By May, when the next issue is finished, Arriaga hopes to have distributed all 4,000 books the staff ordered last year. But The Chanticleer office tells a cautionary tale. There, some 600 or so leftover copies of the 2008-09 book still linger in boxes—thousands of dollars in yearbooks that have never been opened. As alumni and current students request old books over time, this pile should dwindle, says Brian Crews, assistant director for activities and programs at the Office of Student Activities and Facilities and the advisor to campus publications. But several hundred old books currently sit in permanent storage, awaiting the occasional alumni request for an old yearbook.

Those aging Chanticleers are joined by another set of stragglers, a hundred or so yearbook-shaped cardboard boxes marked with a distinctive post office stamp: RETURN TO SENDER. Every fall, the staff mails a copy of the previous year’s book to each member of the newly minted graduating class. But if the address on file for the student is wrong or incomplete, the package bounces back and lands right where it started, on the floor of the UPB office. Then Arriaga and her staff of about 20 have to lay off their duties putting the current yearbook together and track down those seniors who didn’t get their free copy—and pay to mail it out again. It’s a Sisyphean task, and the abandoned stacks of returned yearbooks from prior years attest to this.

But it wasn’t always such a struggle to get Duke students to care about The Chanticleer. In 1912, a group of enterprising gentlemen at Trinity College, the young Southern university that would eventually become Duke, spent the better part of a year convincing their administration to create a yearbook, or “annual” for students. They decided to call their inaugural book The Chanticleer, an old fashioned word for rooster, then a popular symbol for making an announcement.

The characters that people the original Chanticleer read a little like a who’s-who guide to the RoomPix website. There’s a page dedicated to the college’s three former presidents, Braxton Craven, John Crowell and John Kilgo. Staring stone-faced from the faculty pages are William Preston Few, Frank Brown, William Pegram, William Wannamaker and Robert Wilson.

That first volume was a smash hit, and except for a brief interlude in 1918 when the bulk of the student body went off to fight in World War I, The Chanticleer has put out an issue every year since. From providing a list of the Duke students killed in World War II to documenting the days when professors smoked pipes during lecture, The Chanticleer has provided a consistent—if necessarily incomplete—record of student life on campus.

But somewhere along the way, the enthusiasm of those very students started to lag. Beginning in the late 1990s, the student activities fee, originally created explicitly for the purpose of funding The Chanticleer, began to sag under the weight of the number of student groups demanding funds. Suddenly the yearbook, which commanded far and away the largest budget of any organization, found itself fighting for its life.

In some ways, it’s not hard to see why. In the era of online photo albums, it can be hard to justify the incredible expense of their paper ancestors. “We have a fixed pot of money, lots of student groups on campus, and more often than not the number of groups increases year to year,” said senior Max Tabachnik, chair of SOFC, the DSG body that determines yearly funding for student groups.

Every year The Chanticleer, whose budget currently hovers around $86,000, is a low-hanging fruit when it comes to making cuts. It’s a glaring figure on SOFC’s $770,000 budget, demanding more funding than the entire sports club council (annual budget: $85,000) or the Duke Partnership for Service ($52,000). The only student group that currently outpaces its spending is the UPB, which divvies up its spoils among more than a dozen publications.

But The Chanticleer’s pot-o’-gold is also nearly $50,000 less than it was two years ago. In September 2008, students summarily rejected a referendum to increase the student activities fee and sent SOFC scrambling to cut costs. The ax came down quickly on The Chanticleer, which lost $25,000 in a single swipe. Not wanting to turn to printing ads or charging for books, the staff said goodbye to 60 pages of their publication, as well as the thick matted pages and high quality ink they’d been using. But when another $25,000 got sheared off the following year, they started to panic.

“The Chanticleer cannot sustain any additional cuts,” said Taylor Martyn, Trinity ’10 and the editor of last year’s volume. “Basically, if the budget is cut again, we will not be able to afford to continue producing a book for the University.”

In some ways, that plight is no different than what other universities are facing. Agromeck, the yearbook at North Carolina State University, sold only 750 copies in 2006 to a student body of 30,000. The following year, that number was 300, and a year after that they barely managed to eke out 200 sales. At Towson University outside Baltimore, the yearbook staff convinced just 25 students to buy a copy of their book in 2009 and had to close shop the following year. They joined the University of Virginia, Purdue University, Mississippi State University and Mount Holyoke on the growing list of schools that no longer print a student yearbook.

But what makes Duke’s book different than many of its flailing contemporaries—and its editors say it’s an important distinction—is the fact that here every student can have a yearbook, not just those with the means and will to shell out $100 for a copy. That means that Liddy Dole’s entire graduating class can now dig out old photos of their classmate-turned-political-machine when she was an impressionable 20-something, and that all of the 2010 seniors share the same photos of flaming benches, Jay Sean’s LDOC and Senior Bhangra.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“In my opinion, a yearbook is the best way to memorialize a year in the life of a student,” Martyn says.

The publication’s editors and advisors also point out that all this apocalyptic talk about ending the yearbook to save students money may be overblown. Yes, the yearbook is a major cash guzzler, but it’s also not exactly sending the student activities budget into the red.

“Student organizations are pretty well-funded here at Duke,” Crews says. “While it’s probably good to challenge The Chanticleer to look efficiently at their budget, SOFC has plenty of money, even an excess of money.”

In last year’s Chanticleer, there is a four-page spread on Tailgate. No captions. No explanations. Just 10 photographs of leopard print, neon leggings and Busch Light boxes re-appropriated as hats. In one of the pictures, a woman in a soaked white T-shirt shoots a water gun full of beer; in another a sheepish security guard carries a stack of solo cups through a crowd of students dancing on crushed beer cans.

The yearbook is a strangely self-conscious entity, meant to record not so much who we are as the side of ourselves we are most proud of. Its pages are filled not with disgraced Duke researchers or battles over the existence of progressives, but with rock climbing contests, DukeEngage trips and the blue-and-white throngs descending on Cameron Indoor Stadium.

But it is also a snapshot of a place that changes so quickly that it’s often easy to forget just how much has stayed exactly the same. The Chapel silhouetted against the night sky in the 1950 book is the same as the one in the 2010 book. In the 1976 yearbook, the editors republished a Chronicle column by Rick Moore, Trinity ’77, bemoaning the state of romantic relationships on campus. “For some time now,” he wrote, “there has been an increasing chasm developing between love… and sexual activity.” Move over, Karen Owen—it turns out our parents’ generation was doing exactly the same thing. The Chanticleer is a link to that Duke and an anchor to our current moment.

“Of course people have their Facebook pictures and everything, but it’s so impermanent,” Crews says. “You’re not going to pick that up years from now and say, ‘Here’s what was happening at Duke while I was there.’ There’s something to be said still for having a book.”