When Duke alum Wil Weldon saw Reynolds Price in mid-December for what he did not yet know would be the last time, his former professor gave him a stern warning.

“He pointed his finger at me and he said, ‘Don’t you tell anybody at Duke that I’ve been sick. I don’t want them to think I can’t teach,’” Weldon, Trinity ’96, recalled.

Price’s famed class on the Gospels was cancelled only after he suffered a fatal heart attack Jan. 16.

When Price returned to his alma mater more than five decades ago, he was determined to teach for as long as it would let him. Retirement was never part of his plan.

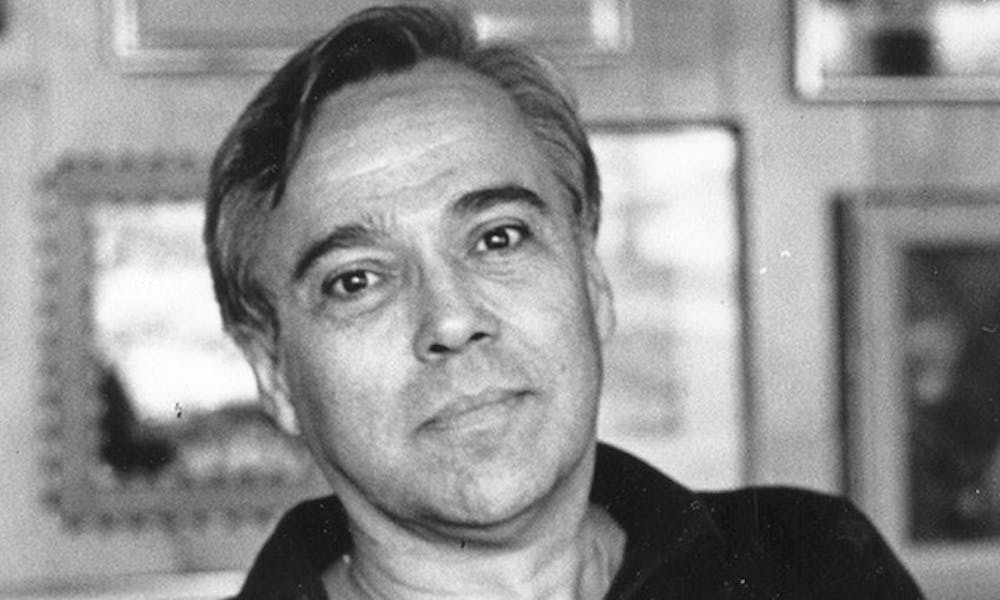

Price explained his meteoric rise from literary unknown to esteemed professor and preeminent Southern writer as a journey from teacher to teacher. He was forever grateful to both the women who ran tight ships in the rural Carolina schoolhouses and literary luminaries at Duke, and he repaid the debt over a lifetime in the classroom.

“I’ve just tried to be an interesting and useful teacher, someone you wake up in the middle of the night and say, ‘Gosh, remember when old Doc Price...’” he said in “Pass it On,” a newly released documentary directed by Weldon.

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Anne Tyler, Women’s College ’61, met Price when he registered her for her first course as a student and his first as an instructor. In a later class, Tyler and her peers were challenged by Price to write short stories that brought his voice and author J.D. Salinger’s into harmony.

“I trust we’ve all given up the attempt by now, but that doesn’t mean Reynolds hasn’t continued to have the most pervasive influence upon my work,” Tyler wrote in an e-mail Feb. 8. “I think of him every time I consider the whole lonely and mysterious craft of writing.”

Price saw writing and teaching as part and parcel of his gift, said David Aers, James B. Duke Professor of English. Tyler was not the only student to graduate into friendship with Price—personal connections were a cornerstone of his teaching.

“I think he saw teaching as not just imparting knowledge or information but as an engagement with a complete human being,” Aers said.

The mystique of teaching

When he began teaching at 25, Price had Duke under a spell. He dashed around campus with a blue coat thrown over his shoulders that students mistook for a cape, Tyler wrote in the July 1986 issue of Vanity Fair.

The mystique crested with the publication of Price’s first novel, “A Long and Happy Life,” in 1962. Author Josephine Humphreys, WC ’67, read and loved the novel and, after glimpsing his picture in Seventeen magazine, judged Price to be the handsomest man she had ever seen.

Humpheys and about 100 others crowded into an auditorium to audition for a spot in Price’s writing class. He scrawled the first sentence of one of his short stories on the board, giving students an hour to carry on the plot.

Humphreys won a spot, but she was too shy to speak in class. She spied him on campus one day but looked down to avoid him.

“Don’t be so stuck up,” Price hollered from across the quad in his booming baritone, finally putting Humphreys at ease.

“Class with him is really hard for me to explain—it was like magic,” said Humphreys, who later won the Hemingway Foundation/PEN award. “I think he knew that we were in awe of him, and he tried to make that easier.”

On the first day of his Spring 2008 course on John Milton’s poetry, Price—left paralyzed after a bout of cancer—rolled up to his desk, raised on a platform to set him above his students. Braden Hendricks, Trinity ’10, didn’t recall a cape, but he felt starstruck just the same.

Hendricks visited Price during his office hours because he felt class participation—a huge chunk of the grade—would be a problem for him. He was shocked to find himself opening up about his parents’ divorce.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“He would ask polite but probing questions, kindly curious with a hint of playfulness,” Hendricks said. “If you were brave enough, he let his guard down.”

Price was aware of the curious hold he had over students, noting that although he had been decorated with many prizes, he had never won a teaching award at Duke.

“There are two possible reasons. One is I’m no damn good at it, or there’s something about me which has students a little bit edgy,” he told Weldon. “I love that—far better to be that than to be somebody’s pet dog, somebody’s pet teacher.”

Price’s stay at Duke encompassed not only most of his life, but much of the University’s. In Price’s absence, Aers hopes Duke will take a new pledge to embody his values.

“It’s one thing for institutions to say we had this great man, but will you take his values seriously?” he asked. “Will you try and sustain what he stood for? Do you love what he stood for?”

The words’ echo

Humphreys emerged from Price’s courses with ears highly attuned to the sound of words. Although it did not come to her as naturally as it had to him, he endowed her with the sense.

“I think you could lift a sentence out of any Reynolds Price book and I’d recognize it,” she said. “It’s like a voice print—the rhythm and the sound of it is just Reynolds.”

Singer James Taylor never had Price for a teacher, but the two became fast friends in the 1980s, collaborating on a pair of songs: “Copperline” and “New Hymn,” a Price poem that Taylor set to music.

“[‘New Hymn’] was like a slow pitch right through the center to the strike zone for me, so easy to grab hold of and work with,” Taylor said. “I wish that happened more often.”

Price served as a sort of spiritual guide for Taylor, educating him outside the classroom.

“I was raised basically by atheists and had no access to any clear spirituality aside from what accompanies everything,” he said. “As a recovering addict, my program requires a spiritual practice. It’s been very difficult for me, and Reynolds was very helpful.... Those of us who knew him well, we carry him on.”

In the poem “Mid-term,” Price assesses his teaching by the numbers: of some 2,000 students, perhaps 200 looked at him with eyes wide in appreciation. A smaller number paid him an even greater tribute.

“Maybe another 40 or 50 have waked/ in the night years down the line and felt/ a dug-up lost line of verse in the shape/ my voice pressed on it once,” he wrote.

Like many teachers, Price advised his students that voracious reading was key to writing well. Some friends and students say the practice is now a way to stay close to him.

Actor Paul Fleschner, Trinity ’03, shares the reading list Price gave him with friends “almost as an evangelist.” He plans to read the diverse list in its entirety, though it will take years.

“I’m going to keep hearing his voice and the story that he loved to tell,” he added.

Taylor too expects to take comfort in the words Price left behind. But he knows it could never be quite enough—Price has left a void that almost defies description.

“It’s an awful lot that he has given us to have access to his spirit, but I miss him as a friend,” he said. “I just miss him like the devil.”