Three years after two offenders on probation were implicated in the deaths of Duke’s Abhijit Mahato and UNC’s Eve Carson, North Carolina has striven to revamp its probations enforcement system, though state officials say there is still progress to be made.

Two of the three accused of the murders were on probation at the time of the incidents, shocking the University and local communities and illuminating problems within the state’s probation system. Laurence Lovette, who was allegedly involved in both cases, is facing ongoing charges, and Demario Atwater will serve a life sentence for the murder of Carson, who was UNC student body president at the time of her death.

Some lawmakers alleged that the men had been under inadequate state supervision, which then Director of Community Corrections Robert Lee Guy called “a dark cloud” over his agency. Lovette’s probation officer had been assigned 126 other cases with little training and 10 different probation officers had handled Atwater’s case before he was charged in Carson’s murder, the Associated Press reported.

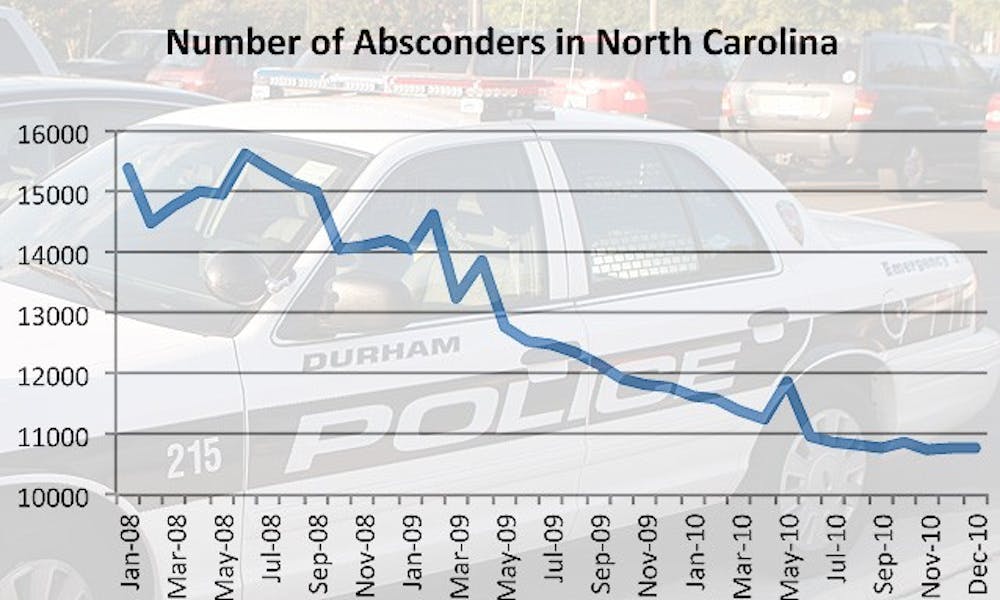

Changes since 2008 to the N.C. Division of Community Corrections, which is responsible for probations enforcement, have resulted in significant progress, said Pamela Walker, public information officer for the agency. According to data provided by the division, the average number of probation absconders per month in North Carolina have steadily declined from 15,642 in June 2008 to 10,782 in December 2010. An absconder is an offender that the assigned probation officer is unable to make their scheduled contact with.

“The entire process has been reworked,” Director of Community Corrections Tim Moose said. “What we’re doing fits right into our goals for criminal justice.”

Walker and Moose said they were unable to provide data regarding the number of offenders who received felony or misdemeanor charges while on probation because they said it would be very time consuming.

Evidence-based practices

Moose and Walker point to what they consider “a culture change” in the way the organization handles each individual offender.

Before, offenders were supervised based on their court sentences, Moose said, whereas now the division also takes into account individuals’ personal backgrounds and propensities to commit future offense—a process he called “evidence-based practices.”

“We now have an offender assessment,” Moose said. “It looks at an offender’s arrest history, family situation, employment, drug or alcohol use, antisocial tendencies and uses that information to determine the risk of a repeat offense.”

Based on this new approach to handling cases, for example, Moose said that Lovette would have likely been better supervised because he would have received an offender assessment within 60 days of sentencing to determine the risk that he would commit more offenses.

Citing findings from the National Institute of Corrections, an agency within the Federal Bureau of Prisons, Walker said that though high-risk individuals are likely to become repeat offenders, low-risk individuals under excessive supervision are more likely to commit additional offenses. This information is incorporated in the training classes for probation officers so that they can better supervise their assigned offenders, she said.

Stricter policies for offenders and the use of new technology is also aiding monitoring.

All offenders are now subject to warrantless searches and routine drug screenings, a practice previously reserved for high-risk offenders, Moose said.

The use of database software—called the Criminal Justice Law Enforcement Automated Data Services—pools information from different law enforcement agencies and started to be implemented statewide in early 2010. Almost all North Carolina counties are now part of the N.C. Warrant Repository, Moose said, which allows local law enforcement to pull up arrest warrants even during routine traffic stops.

Continued diligence

The efforts to reform the Division of Community Corrections are “definitely ongoing,” Moose said.

Since 2008, for example, the organization has seen a marked decrease in unfilled probation enforcement positions. The number of vacancies per month statewide dropped from 119 in July 2008 to just 31 in January 2011. As of last month, there were no vacancies in Durham County.

“There has been a big emphasis on filling officer vacancies,” Walker said.

Local law enforcement officials—including Steve Mihaich, deputy chief of the Durham Police Department—have responded positively to the changes. Mihaich noted that DPD has a “good working relationship” with Community Corrections division, though he acknowledged that the organization cannot possibly prevent all offenders from committing serious crimes.

Duke Police Chief John Dailey said he expects Duke University Police Department to soon begin use of CJLEADS, which will to further strengthen the collaborative efforts between his force and Community Corrections.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.