Physically, Marvin Tillman is the anti-librarian.

With sloping shoulders and a handshake like grasping a baseball glove, Tillman’s past days boxing and playing semi-pro football—he is a former owner of the Bridgeport, Conn. Knights—make complete sense. But he is equally as experienced in library management, and Tillman stands at the helm of what might be the Duke library system’s most valuable asset—the Library Service Center.

Located off NC 147 about 10 minutes from campus, the LSC is a climate-controlled repository for some 3.5 million books, documents and archival materials belonging to the library systems of Duke and several other area institutions.

Since the LSC opened in 2001, it has expanded rapidly, now accounting for 45 percent of the Duke library system’s electronic document deliveries—between 300 and 400 deliveries a day—and processing around 400,000 items a year.

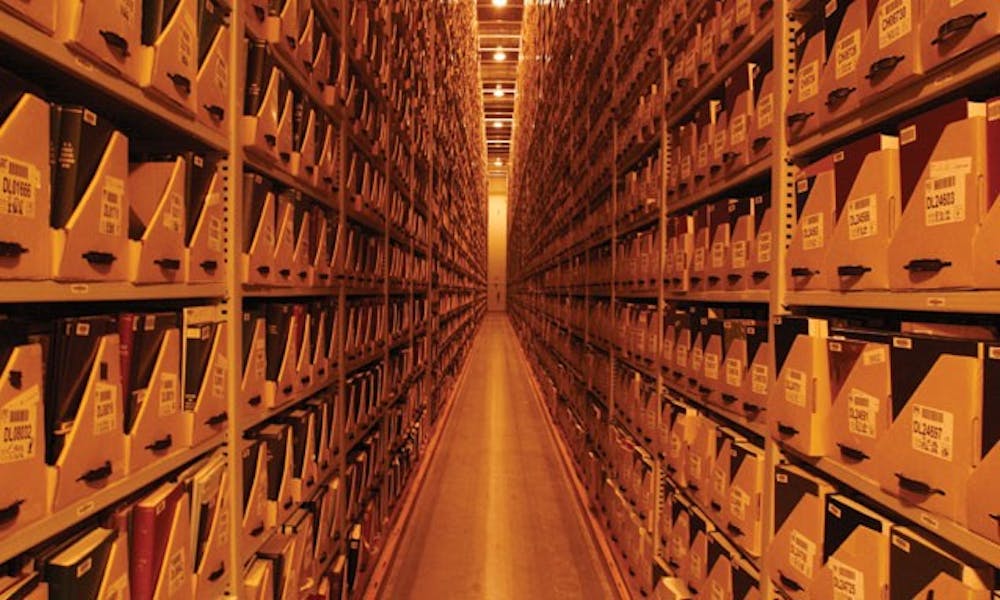

Still, as gargantuan and impressive as the Library Service Center’s holdings might be, they don’t compare in sheer spectacle to the actual warehouse where they are stored. When we entered through a massive steel door plastered with fliers and reminders, the sight was vertiginous, aisles and aisles of material extending far enough to seem almost endless. Spanning two modules—the second built in 2007, with a third potentially in the works—the storage area is 30 feet high and 200 feet long.

During a tour of the facility, Tillman joked that the LSC staffers “do more work before 10 a.m. than [other Duke Library workers] do all day,” and this isn’t hard to believe. Providing service not only to all of the various library branches on campus, the facility houses a substantial amount of material from other sources as well, including the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina State University, North Carolina Central University and the Durham County Library. UNC alone sends 35,000 items to the LSC in a typical month.

Although services are provided to the City of Durham free of charge, the other universities pay a fee to use the LSC, which helps to fund its considerable operating cost. The facility has its own trucks, which make runs to campus twice a day with requested materials, and the other institutions come by each week to pick up their own needs, which are color-coded by destination. Maybe most remarkably, the center also provides a rush delivery service to students that can ensure same-day delivery of material.

“I know how your brain works,” said Robbin Ernest, assistant head of the LSC. “You’re working at different deadlines. When you need something, you need it.”

Tillman added that early in the center’s life, concerns about delivery speed were tantamount among professors and students. But by now, they’ve been assuaged.

“We get stuff out faster than their own libraries,” Tillman said.

But what’s so effective about the LSC goes beyond space provided and documents delivered.

“The center is designed to preserve the material and add fifty years or more to the life of the book,” Tillman said. Books are thoroughly cleaned upon arrival and then maintained in a warehouse kept at 50 degrees Fahrenheit and 30 percent humidity. Such beneficial conditions make the center particularly attractive for storing fragile archival materials, such as writer Nicholson Baker’s extensive American Newspaper Repository, a 5,000-volume collection of 19th and 20th century newspapers that has been stored at the Center since 2004. And the advantages are as much about organization as they are atmosphere.

“[The books are] shelved by count, customer, tray and barcode,” Tillman said. “We never have to do an inventory, because nothing comes in without being scanned, and nothing goes out without being scanned.”

With both computerized and paper records, each book is tied to not only its barcode but also to the barcode of the tray it has been placed in with other similarly sized materials. Subsequently, each tray is electronically married to a certain shelf in the cavernous warehouse. In the run of operations, this means that multiple barcodes need to be scanned in order to remove or check in a book, installing a few levels of security into a task that is seemingly Sisyphean and unfailingly complex: the tracking of millions of physical items.

“Have you ever gone to the stacks in Perkins and not been able to find that material?” Ernest said. “We don’t have that problem.”

In addition to handling the physical copies, the Center digitizes the material as well, both for document delivery to Duke students and faculty and to try and trim stocks down to one copy of each book, in the interest of saving space

Duke isn’t alone in its use of such a location. More than 200 American universities now use 60 such facilities. But in the scope of Duke’s own library system, Tillman can’t speak strongly enough to the indispensable nature of the Library Service Center.

“We’ve got a diamond in the rough here,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.