There’s something deceptive about ePrint.

Its malignance is the most dangerous kind, lurking just beneath the surface; it gets under our skin more than we know. The scant minutes before class are passing at an increasing rate, and there is a paper jam, abstruse error messages, an ink shortage, trays that are conspicuously empty—and all of these unlikely contingencies miraculously result by virtue of the fact that you have an essay due.

Take this situation and add up all the times it transpires throughout one day to countless individuals, and suddenly the presumed convenience of ePrint reveals itself as nothing more than a thin varnish obscuring a malignant evil. Like the finitude of our mortality, we all at some point succumb to this ultimate realization: some days, ePrint’s sole purpose in the world is to torment us.

Venomous evil? This is just ePrint, you say. It’s not that bad. In fact, it’s pretty useful half the time. To such a sentiment, I can only assume that you haven’t truly experienced ePrint. In a guile of false mercy, you have been spared thus far. Its malicious heart still has yet to single you out; the machines of Bostock and Perkins have not yet risen in union against you. Come that inevitable day when all your printing needs are denied by systematic ePrint failure and you will finally understand why some people legitimately fear the notion that artificial intelligence will eventually enslave the human race.

But what makes ePrint so demonic, so virulent? Especially given the fact that in the 10 percent of the time when you receive your prints on your first try at the first printer you come across it actually is ridiculously convenient.

Perhaps its deception is a function of its ubiquity. ePrint is embedded in our daily academic lives to the point of near invisibility. No longer can essays be submitted, readings be read or really anything at all be printed without a Net ID and a swipe of a Duke card. ePrint no longer represents a technological amenity created to help us, in the same way cell phones no longer encapsulate a revolution in communication, nor weigh 10 pounds, nor are even just phones anymore. In a sense, we’ve absorbed them; the fancy or delight we once took in the way they “simplified” our lives have vanished. And at some point in this transformation we have come to expect them to work at 100 percent efficiency, 100 percent of the time. As the reader, however, if you are suddenly fearful you have unwittingly immersed yourself in an anti-technology polemic disguised as an ePrint article, relax. Although ePrint is annoying and perhaps exemplary of our reliance on technology, I not unlike most people approach technology with a cautionary ambivalence, an approach I believe Thoreau was alluding to when he wrote in Walden, “Men have become the tool of their tools... but, I admit, the iPad is pretty cool.”

What, then, are we to make of ePrint? Perhaps it would be prudent to look back and recount its rise and evolution at Duke (especially since this was the point of the essay to begin with). It began in 2003, most likely forming by way of the asexual reproduction of single-celled organisms and emerging from of the dark abyss of Perkins (Bostock didn’t even exist yet!), whose desolate study spaces were characterized by chaos and the environmentally un-friendly wasting of printer paper. The year 2007 brought its next advancement: the establishment of the allotment system. To this day, each student now receives $36 worth of printing per semester, which at one cent per double-sided page equals 3,600 pages (God help you if your classes actually require more). Finally, probably skipping over other milestones, in 2009 the ever-popular 15-minute print queue was created. In a service that seems to bespeak ePrint’s own inconsistency, students’ print jobs are now held in the system so they do not have to run back to their computers to reprint a document if the machine fails to work.

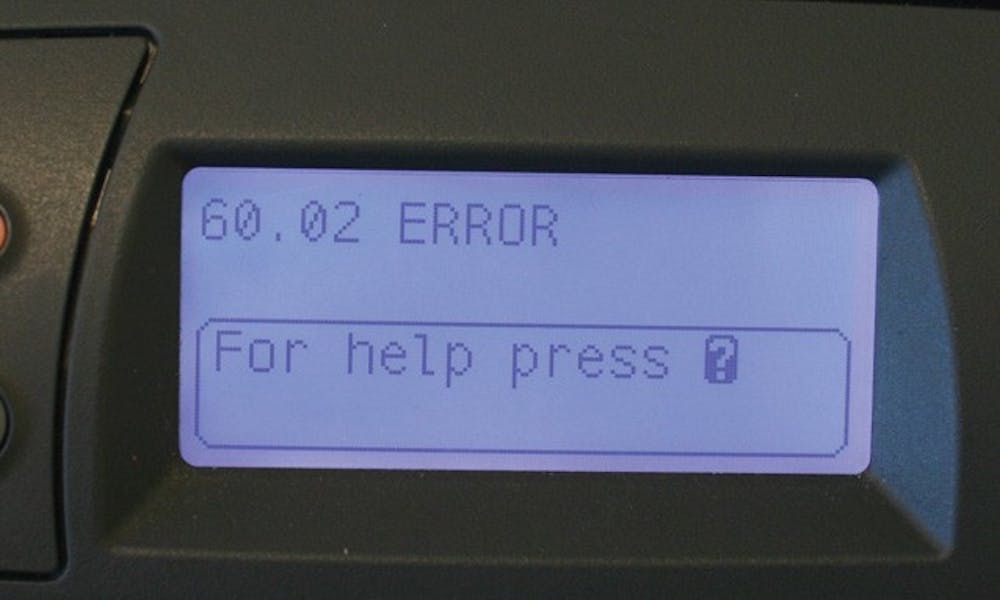

So there we have it, multiple innovations that we have taken for granted and carried on with our lives and the real issues that bring us to the library. As for where the future of ePrint lies, it is already taking form before us. Sleek new printers now greet us as we go to print our readings. Tantalizing in their ergonomic superiority over the older clunkers, we gravitate toward them. They seem poised: impersonal and ready to deliver. We cannot resist. Lured by their promise of faster, better, more streamlined printing, we swipe our Duke cards and, with index fingers waiting to complete the act, we incredulously glance at the minute message-screen:

ERROR---NEEDS SERVICE.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.