When W.S. Merwin walked into room 328 of the Allen Building to teach a master class Thursday afternoon, he found each one of his pupils sitting before an illuminated screen, poised to take notes.

The national poet laureate responded in kind, retrieving a worn green notebook bound with a rubber band from his breast pocket.

“This is my work,” he said.

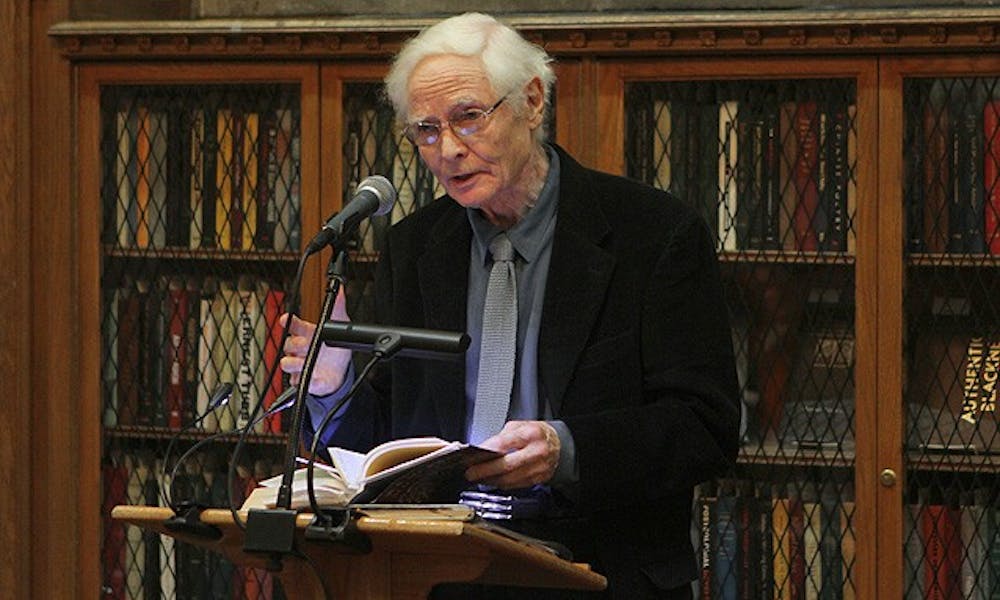

When Merwin gave a reading before a packed Gothic Reading Room Thursday evening, the poems were dressed up, bound in sleek volumes and printed on glossy paper. But it was in the worn green notebook that they found their form and in daily life that they were inspired, the poet explained.

“It may have been a phrase that seemed completely familiar, nothing out of the ordinary... and then suddenly you realize that the train is moving and you’re on it,” he said.

When Merwin, the William Blackburn Visiting Poet at Duke, was named the national poet laureate in July, it was the latest in a long list of accolades. The poet has twice been honored with the Pulitzer Prize, along with the National Book Award, the Tanning Prize, the Bollingen Prize and the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, among others.

“I remember feeling that you were the exemplar of the kind of formal elegance that I aspired to but could not reach,” Professor Emeritus of English James Applewhite, a distinguished poet himself, told Merwin when introducing him in the Gothic Reading Room. “[Merwin’s poems] win us, by delight in their craft and precise representations, to love them. They help us make our souls. Help me welcome the maker of the most essential connective poetry of our time.”

Merwin noted that he had deep reservations about being designated as the nation’s poet, explaining that it “seemed so un-me.” He ultimately decided to accept the post when he realized it was an opportunity to promote the world view that all life is interconnected.

Characterized by some critics as a member of the “ecopoetry” movement, Merwin said he never begins a poem with a desire to advocate for the environment. Such a process, he explained, would result in the composition of propaganda.

Yet a love for the natural world ultimately shines through in the pieces, Applewhite said.

“[The poems] bring us a sense of belonging, from beyond conscious knowledge, restoring us to our primal selves, before thought and feeling were pulled apart,” he said. “They do this by locating us in fields, beside rivers, in long-time inhabited places, which represent locally the wider universe that has evolved with us. This poetry is the felt meaning of residence on Earth. It gives us back the dignity of living in a world to which we have a natal relation.”

Thursday’s reading, bookended by poems about animals, offered the audience a condensed chronology of the poet’s decades-long body of work.

Reflecting with a small group of students in the master class, Merwin noted that many of the relics of his childhood have been destroyed. The church he attended as a boy burned down. The house he grew up in was purchased by a developer who dismantled its porch and “put asbestos shingles on it.”

It is a process of loss that everyone must endure, he said.

“Now it seems to be happening faster than ever,” he added. “You go back in a few years and the whole thing is completely gone.”

Life in a small French village that had been the same way for centuries thrilled Merwin when he was in his early 20s.

“The past was right there,” he said. “I grew up in a place where no one even knew who their grandparents were.... I was hooked.”

Merwin’s poetry can have this power for readers.

“Human time, in his evocations, encloses permanencies in its transiency,” Applewhite said. “Memory is a strange, dream-like part of the spirit-self which knows of times beyond the brief flash of consciousness.”

When speaking with students and before the audience of the Gothic Reading Room, the poet’s inquisitive spirit was made plain. He asked many questions he said could not be answered.

“Where is the poem? Is it on the page? What happens if you lose the piece of paper?” Merwin said. “These are questions that you want to keep coming back to.”

Merwin noted that poems written for children are among his favorites, a fact that begets more questions.

“Does this mean that the part of us that loves poems is a child?” he asked. “Maybe it does. Wouldn’t that be wonderful.”

Merwin questioned young writers who attended the master class about their reliance on technology, noting that he is deeply concerned about its implications for poetry. With laptops on hand, some young writers feel no need to use the notebook Merwin keeps in his breast pocket.

“To me it sounds different, what is written that way,” he said. “There is potentially a lot of loss to going that way.... I can’t believe poetry can survive without ever really hearing it at any point in the composition.”

Although Merwin remains loyal to pen and paper, Applewhite said he sees an evolution in the poet’s work over time.

“He’s always been, though, a marvelous poet. His first blank verse stuff was good in its kind, but it was much more academic and traditional, and this is really innovative and fresh,” Applewhite said. “He’s 82 years old and he’s writing very fresh stuff.”

The poet closed the reading by sharing poems he has composed following the publication of his latest volume, “Shadow of Sirius,” which won the Pulitzer Prize. The last verses of “A Coming of Age” suggest a certain maturity: “It will not be enough. It will be enough.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.