One morning this summer, Dan Aced stood on N. Buchanan Blvd., waiting for the bus he takes to work each day.

Shortly before the bus arrived, he spotted a man in a suit—a Duke administrator, he guessed—chatting with a man in a hard hat in front of 610 N. Buchanan, the block’s dilapidated white house. A bulldozer crawled down the street.

By the time Aced stepped off the bus at the end of the workday, the so-called “lacrosse house”—the site of the deeply misunderstood party that sparked headlines nationwide and shook Duke to its core—was gone.

From the moment Crystal Mangum wrongly accused three Duke lacrosse players of raping her there in March 2006 to the day charges were dropped the following spring, University administrators, law enforcement officials and countless pundits agonized over what exactly took place within the home’s splintering walls.

The infamous house fell to the ground less than two months after the Duke men’s lacrosse team won its first national championship, making 2010 a poignant year for the lacrosse case, said Phail Wynn, vice president for Durham and regional affairs.

“These things do bring closure to this chapter in Duke’s history,” he said. “We can move forward from here.”

By all accounts, the July 12 demolition was a cinch—residents and Duke administrators alike noted that the structure was already collapsing in on itself, after all.

Mike Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations, said the house was beyond repair and demolition was the most logical approach.

“[The events in that house] captured the attention of not just the city but the nation,” he said. “Obviously there are some people who will never get over any particular issue or incident, whether it’s lacrosse or any positive or negative matter…. For the vast majority of people driving past, that house was a decrepit structure that was falling apart.”

Yet K.C. Johnson, a professor of history at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York Graduate Center who has chronicled the case since it broke on the blog Durham in Wonderland, said leveling the house also gave the University the opportunity to deal with a “public relations problem.”

As a physical symbol of the case, the house was also a reminder of Duke’s own complex reaction to it. When the rape accusation was first presented, faculty, administration and students divided over how to respond, and groups came out strongly both for and against the players long before the verdict of innocent was handed down.

“The decision to tear down the last visible remembrance of the case fits the general Duke approach since 2007,” he said. “Duke had two choices: to ask hard questions or to sweep things under the rug…. Clearly Duke has chosen the latter option.”

A small crowd gathered to watch the house fall, but none stayed for the slow clean-up that followed, the Durham Herald-Sun reported.

The rubble is destined for a landfill, Richard Davis, superintendent with the O.C.

Mitchell construction company, told the Herald-Sun.

“Tearing it down was no problem,” he said. “Carrying it off is the problem.”

Indeed, some think the legacy of the house and what it stood for will be harder to shake.

“You can remove the physical infrastructure, but it’s so easy to access the digital record of what Duke did on the Internet,” Johnson said. “You can’t whitewash the past: it’s there and it’s readily accessible.”

***

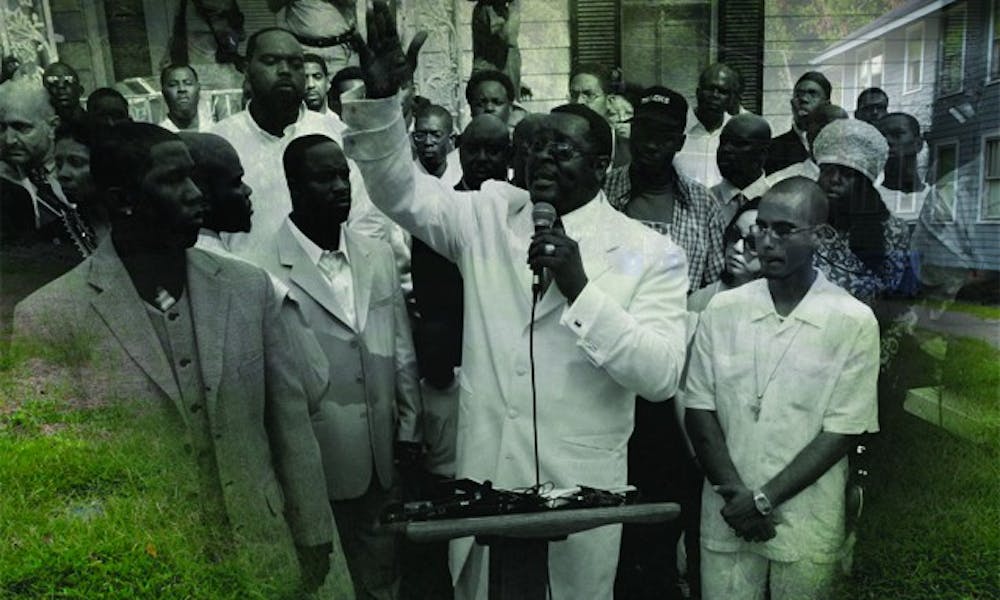

When the case erupted in 2006, the scene of the alleged crime was a focal point of the firestorm.

Supporters tacked posters to the house’s walls; protestors paced the sidewalk, banging pots and shouting for change; broadcast journalists reported from the lawn.

Four years later, long after the truth about what took place at the infamous address finally emerged, the television crews and the players they scrutinized had picked up and moved on. But the house at the center of it all was frozen in time until the date of its demolition.

The case still lives in the courts, which made it difficult to lay the house to rest. Administrators were forced to leave the property as it was that night because it was considered evidence in the ongoing civil suits spawned by the case.

This year, Duke notified attorneys representing members of the 2005-2006 men’s lacrosse team of its decision to tear down the house and gave them the opportunity to photograph the property, clearing the way for the construction crew, Schoenfeld said.

The face of neighborhood has changed drastically since the start of the case. Administrators purchased the so-called lacrosse house along with 11 other houses and three vacant lots off of East Campus in February 2006, hoping to revitalize the neighborhood.

Several houses on the block received face-lifts. Many current residents did not live in the neighborhood when the case broke. Yet the constancy of one house inevitably conjured up the past.

Years after its last occupants had packed their bags, the house’s sagging porch was brimming with junk mail, phone books and broken beer bottles. The door was padlocked, but the doorbell still rang. A black question mark was spray-painted on the back wall.

“How could you not think about the case when your eyes passed over the house?” said one woman who declined to be named due to the sensitive nature of the case, gesturing at the now vacant lot from her kitchen window.

The woman, who has lived in the neighborhood for just a year, said she was surprised when she laid eyes on the house that was the subject of so many headlines: it was so much smaller than she had imagined.

Elizabeth Wheeler moved into the neighborhood earlier this year, but the case was never far from her mind while the house was standing.

“The whole thing was just kind of strange,” she said. “It was just kind of creepy.”

With the house gone, the case has quickly receded from Wheeler’s mind. Now when she jogs on N. Buchanan Blvd. each morning, she sees a vacant lot and nothing more.

The case is of questionable relevance to Duke’s own students. Even the current senior class was still in high school when the scandal erupted. Senior Nick Altemose said the case has mainly been referenced jokingly his time at Duke.

“I think maybe this is just the final breath of an already dying story,” he said.

Yet a judge is still weighing several civil cases spawned by the incident. Players who were not indicted have filed suit against Duke, and although the University settled out of court with the three players who were wrongly accused, their suit against the city of Durham is still pending. The judge’s decision on the merit of the suits could bring new documents to light and force administrators to take the stand, Johnson said.

“There would be nothing like that in terms of the history of American higher education if the civil suits move forward,” Johnson said. “[The demolition of the house is] a temporary closure. Whether it sticks remains to be seen.”

***

The fate of the lot itself is still an open question.

Wynn said members of the Trinity Park Neighborhood Association hope another single-family home will be built on the property.

Schoenfeld said several builders have approached the University with interest, but he noted the lot’s small size and odd shape could complicate its sale for residential use.

The possibility of building a park or urban courtyard on the lot has also been discussed, Schoenfeld said.

“I think it’s wonderful what Duke has done, and I would love to see it turned into a park—a place where older members of the community can sit and enjoy nature,” resident Frank Crigler said.

Yet the same anonymous woman who said the physical presence of the house constantly reminded her of its history disapproved of the idea of a park, fearing it would memorialize the case.

“If a new home was built and a family moved in and started raising kids, that land would have new life,” she said.

A newcomer might not suspect that a house ever stood in the vacant lot off East Campus.

The home has been carefully disembodied, its front steps leveled and its basement filled so that only even ground remains.

In less than two months’ time, weeds and what looks like ivy have already begun to take root in the newly cleared soil, concealing any scars left by heavy machinery.

Yet the addresses on N. Buchanan Blvd. inexplicably skip from 608 to 702. A black stone that once formed a path to the front porch remains. And the soil where the house stood is redder and rockier, not yet settled.

A neighbor noted that she continues to give directions to her home in relation to the “lacrosse house.” More than four years later, it’s still a nearly fool-proof point of reference.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.