The mayor of Kunshan, China is the proud owner of a signed Duke basketball.

Soon, though, his city—which is located near the metropolis of Shanghai—will receive much more of Duke than a piece of its memorabilia.

A five-building Duke campus is set to open in the region by January 2012, when it will host some of the Fuqua School of Business’ programming. And Kunshan is not the only region partnering with Fuqua, which has connections with London, Dubai, New Delhi and St. Petersburg, and has plans to establish programs in other areas as well.

Because of Duke’s growing international presence, the University created a new Office of Global Strategy and Programs April 16.

“We have been doing global programs since 1995, so having a brand for global business education is not new,” said Fuqua Dean Blair Sheppard. “What’s new is having a physical presence that supports the activity.”

Although the business school is the driving force behind much of Duke’s internationalization efforts, it is not the only area at Duke that is looking to conduct programs abroad. A June delegation sent to the Kunshan site included the deans of many graduate programs as well as Steve Nowicki, dean and vice provost for undergraduate education.

Outside of Kunshan, the University has ties in Singapore, with the Duke-National University of Singapore Graduate Medical School, completed February 2009.

As the University becomes increasingly global, it is using its locations across the world partially to enhance its international presence.

“At the Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, you drive up the hill and the first thing you see is Duke,” Sheppard said. “The more people we have wearing Duke T-shirts in Shanghai, the more people we have wearing Duke bags... it’s a funny thing, it helps brand our brand. And that’s our goal.”

Venturing abroad

The University’s presence abroad dates back to the 1990s, when the office of the vice provost for international affairs position was created in 1994. In the 2006 “Making a Difference” strategic plan, administrators cited challenging international events, including the attacks of Sept. 11 and invasion of Afghanistan, as reasons why the University “must forge international partnerships to enhance education and research.”

And as Duke establishes more programs abroad, more international students are coming to study at the University. The number of international students in the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences alone has increased by at least 12 percent in the past five years.

In an increasingly global world—and with more international students studying at Duke’s Durham campus—making connections with foreign countries is important, said Sanford School of Public Policy Dean Bruce Kuniholm, who formerly served as vice provost for academic and international affairs.

Sanford already has several international programs, including the new Global Semester Abroad projected to start next Spring, in which participants will spend half of a semester in China and the other half in India. Additionally, the Duke Center for International Development, which is part of Sanford, currently trains foreign officials in Durham through its Executive Education programs

But Kuniholm, who was a member of the early June delegation that visited the site in Kunshan, said Sanford has plans to set up more international programs, possibly partnering with Fuqua.

“We have an obligation to internationalize our faculty, student body and curriculum so that our students are better suited,” Kuniholm said. “Bringing those people here not only helps their development, but it helps our students. We are not an island.”

Establishing programs abroad also allows countries to share their education practices, especially since the Western liberal arts tradition is foreign in some regions, Nowicki said. By contrast, many other countries, including China, focus on placing students on track for specific professions.

“They need to understand what we are doing in our liberal approach, and we need to understand what they are doing in their more professionally-tracked approach, and we need to understand what are the points of intersection that would benefit our students,” Nowicki said.

In total, Duke has established partnerships and exchanged agreements, including research agreements and departmental partnerships, with more than 300 institutions across the world, according to the Duke International website.

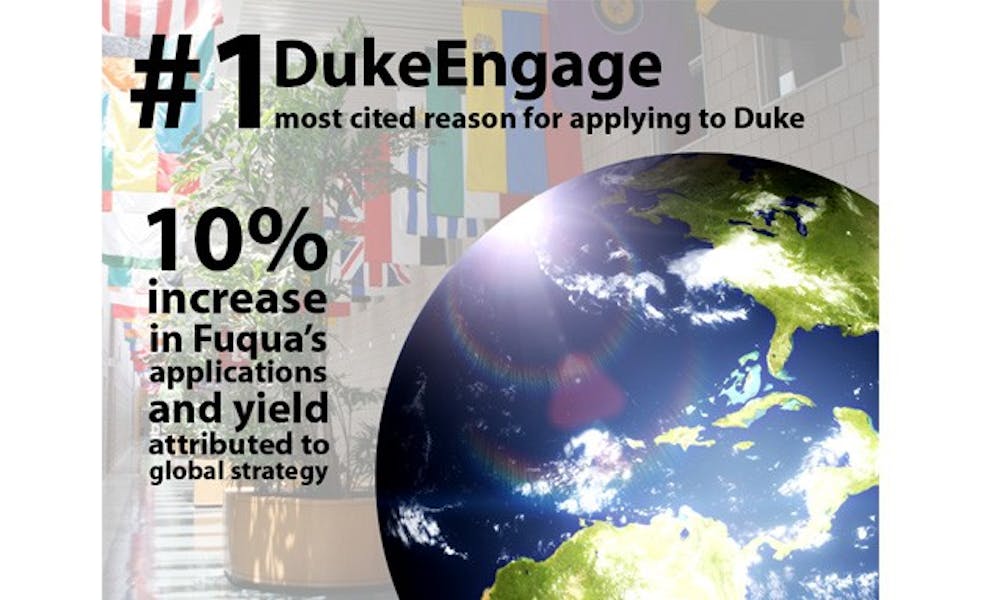

And venturing abroad may be attracting more applicants. Undergraduate admissions materials often emphasize study abroad programs and DukeEngage international projects—among domestic applicants, DukeEngage is cited more than anything else as why students choose to enroll at Duke, according to Director of DukeEngage Eric Mlyn. And Sheppard said Fuqua has seen an increase in applications since emphasizing global education. The school has seen a 10 percent increase in its applications in the past year, and its yield also increased 10 percent, he said.

“If you dig and ask people why, they say that it’s because of your global strategy,” Sheppard said.

A better “brand”

Going global is not unique to Duke, however. Many other universities have engaged in what some call an “educational gold rush”—New York University recently established a full undergraduate program in Abu Dhabi in the Persian Gulf, and many other universities have created international programs that differ from studying abroad.

But Sheppard said Fuqua—whose website claims that its Cross Continent MBA Program is one of a kind—has a different approach to establishing global networks. Many schools are driven to use global programs as revenue generators, but Sheppard said he is wary of building up the Duke brand so much that the school loses its unique size.

“We probably should be a little bigger, but not much,” he said, adding that Fuqua does not need to expand by much to be competitive with other top-tier business schools. “If you go a lot bigger you lose a sense of what makes the place special. NYU doesn’t have the same kind of campus-based, community-based type of education. They could get as big as they want.”

Sheppard emphasized that the business school is careful not to extend itself in certain locations merely to turn a profit. Instead, the school seeks out locations that are some of “the world’s most important economic regions,” according to the Cross Continent MBA program’s website.

“The problem is as soon as you start doing it for market-based reasons you end up making decisions that you don’t want to,” he said.

That was the case with the University’s first international campus founded in 1999—the Fuqua School of Business Europe in Frankfurt, Germany, Sheppard said. Many of the site’s offices were cut due to declining interest among European students, The Chronicle reported in 2002. The site was later closed because of overexpansion, enrollment and financial issues.

“That was a case where we actually followed a financial offer. We learned, if you take a step back and say where is the optimal place to be in western Europe, you wouldn’t have said Frankfurt,” Sheppard said. “The first thing we learned is don’t follow money, go to the right place.”

Duke is careful to establish itself only in regions where it has an academic interest, said Gregory Jones, vice president and vice provost for global strategy and programs.

“We might get an overture from a wealthy country that’s financially quite positive, but if we don’t have the faculty or it’s not the right culture... it would be very mistaken for us to just look at the financial resources,” Jones said.

The University must also ensure that its international programs do not waste money. Most funding for these programs comes from external resources, such as the foreign governments themselves. The Kunshan government, for instance, is providing 200 acres of land and footing the bill for the five-building campus.

But the situation is different in other corners of the world—the Indian parliament is currently considering a bill that would require universities to invest at least $11 million before establishing a university in the country, which could be a possible deterrent for Duke, Jones said. Investing in locales without strong financial systems—such as sub-Saharan Africa—may prove difficult, he added.

As the University attempts to trim its administrative budget at home, however, Jones admitted that devising a global strategy seems strange.

Although the possibility of using foreign programs to turn a profit exists—and many universities are venturing abroad for this reason —administrators are quick to acknowledge that Duke’s focus is different.

“There are some institutions that are going largely to plant their own flag and do what they do in the U.S. now in another context,” Jones said. “Our approach has been to develop deep relationships and to spend a lot of time listening to what our partners hope and want to develop.”

Although most of the University’s global ventures are partnerships, Duke’s name receives substantial publicity because of its investments across the board. Mlyn said DukeEngage programs help spread the Duke name, adding that its projects have been featured in local newspapers in countries such as Turkey and Vietnam.

“Utilization of international partnerships as a strategy places Duke in a competitive advantage in recruiting the best talent, and also to build a bond with lifelong learners that makes Duke a ubiquitous entity in their lives,” according to an article about Duke’s brand published earlier this year by Henry Alphin, a Drexel University graduate student.

As is clear from the Duke logos plastered on the burgeoning international programs and Duke Athletics memorabilia around the world—even in the Kunshan mayor’s office—Duke is venturing outside of Durham. But it still has its original reputation to uphold.

“It’s clearly reputational for us. We can’t afford to compromise it—if we do things of low quality, it will hurt the overall reputation of the University,” Jones said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.