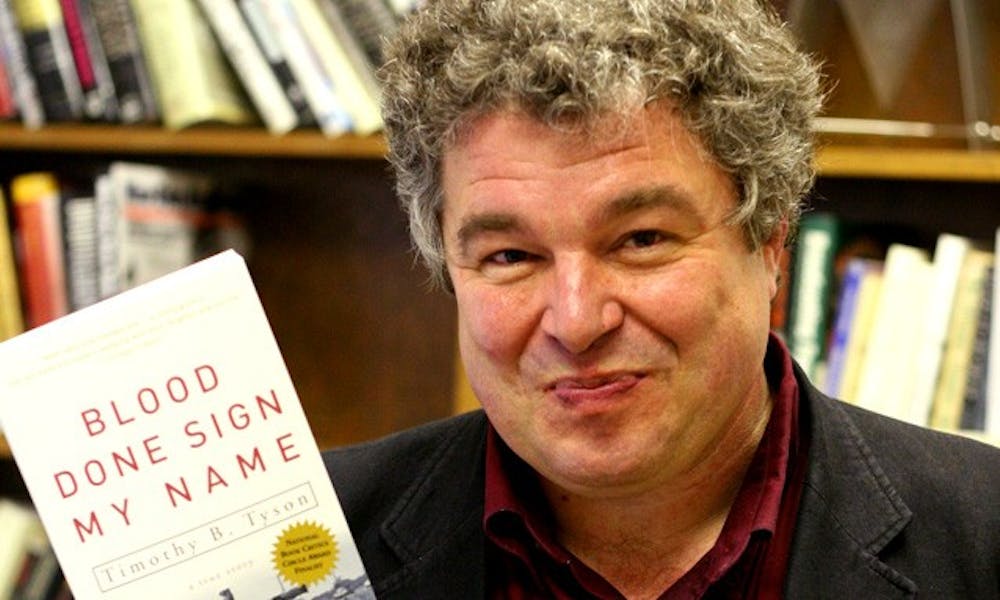

Over the past two decades, Tim Tyson has watched his freshman year civil rights paper evolve into a major motion picture.

The narrative roots of Blood Done Sign My Name, a 2004 book whose film adaptation opened Friday, can be traced back to conversations that took place at the family dinner table when Tyson was a young boy. Tyson, a senior research scholar at the Center for Documentary Studies and visiting professor of American christianity and southern culture at the Divinity School, moved to Oxford, N.C. in 1970 when his father Vernon became the new preacher of the town’s Methodist church.

The white Vernon surprised the deeply segregated town, preaching colorblind love and acceptance. After the murder of black Vietnam War veteran Henry Marrow and the prejudiced acquittal of the three white perpetrators, a grassroots civil rights movement took the town by storm, unfolding before the then 11-year old Tyson’s eyes.

Tyson first tackled the Marrow story in an assignment while attending the Univeristy of North Carolina at Greensboro in 1982. He built upon his original research eight years later in his master’s thesis while working toward a Ph.D at Duke.

“Though it adhered to all the professional norms and displayed a young, fumbling but perhaps promising historian at work, it also was a species of lie,” Tyson said. “You could read the whole thing and not know that I lived there and knew a lot of these people.”

Understanding his own lack of objectivity, Tyson “wisely moved to other subjects” and set his master’s thesis aside. While teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Madison from 1994 to 2004, Tyson advanced to the forefront of African-American studies, winning numerous national teaching awards. But as he was working on another history book in 2001, Tyson could not suppress his personal memoir any longer.

“This story just came spitting out of me,” Tyson said. “There was a kind of convulsive quality to it.”

Tyson wrote about 115 pages in the first month, shedding his previous, more “professional” historian tone for the “new and different” first-person. The Crown Publishing Group published the memoir in May of 2004 to great critical acclaim, and Tyson returned to Durham that year as a John Hope Franklin Senior Fellow at the National Humanities Center.

After yet another transformation, this time featuring a play adaptation by writer-actor Mike Wiley, the story seemed destined to reach the film medium. And when writer-director Jeb Stuart, also a North Carolina native with a preacher father, came across Tyson’s memoir, he was immediately drawn to it.

“It was a very North Carolinian story, which appealed to me,” Stuart said. “Tim’s book had a terrific voice to it.”

Stuart, who penned the screenplays for Die Hard and The Fugitive, was first recommended the book by close friend and Board of Trustees member Robert Steel, Trinity ’73. Steel knew Stuart was looking for a “more intimate story” to be his first feature in a decade, and Stuart found the narrative’s unique placement within the civil rights movement especially refreshing.

“There was a different tone to it: King was dead, Malcolm X was dead,” Stuart said. “A lot of African-Americans came back from Vietnam, where they had fought hand in hand with whites, [as] second-class citizens.”

But when Stuart contacted Tyson about making the film, the historian was wary. A Hollywood producer had approached Tyson during his Duke days in the mid-’90s, inquiring for the rights to Tyson’s dissertation on local NAACP branch president Robert F. Williams. When the producer asked for Tyson to create a more heroic white figure, Tyson backed out.

In a recent Wall Street Journal guest blog essay titled “Why Historians Hate Hollywood,” Tyson related his general mistrust of the way the film industry usually depicts civil rights movements.

“In typical Hollywood movies, we get very clearly marked villains and a very uncomplicated white South,” Tyson said.

Unlike the many agents of bankable Hollywood stars who wanted Tyson to make the script more conventional, Stuart respected the original vision.

“Jeb and I saw eye to eye,” Tyson said.

Stuart and his team began location scouting in 2008, eventually settling on the small town of Shelby, N.C., for the bulk of the filming. Oxford, Stuart recalled, was unable to accommodate the film’s sizeable cast and crew, particularly during the march and protest scenes.

“It felt a little like Lawrence of Arabia,” Stuart said.

Tyson stayed on set for nearly every day of the film’s creation, watching childhood memories re-created before his eyes. Tyson’s father, portrayed in the film by NYPD Blue vet Rick Schroder, visited the set and was profoundly affected by this surreal experience.

“I looked over and my father was weeping,” Tyson said. “You’ve got this sense of your life being marked.”

One of the on-set highlights for both Tyson and Stuart was the incorporation of John Hope Franklin into the film. Franklin, who passed away in March 2009, makes a brief cameo during the Raleigh protest scene. During Franklin’s visit, Tyson ordered cases of his autobiography Mirror to America, and Franklin signed copies for the whole crew.

“That meant so much to me,” Tyson said. “He was an important mentor.”

While there, Franklin also talked to actor Nate Parker, who portrays the activist Ben Chavis. Franklin told Parker how he had debated against Henry Lowe, Parker’s real life character from 2007’s The Great Debaters, becoming so close with him that Franklin was a pallbearer at his funeral.

“That meant the world to Nate,” Stuart said, “to capture a little piece of history like that in a living person. That was the magic of John Hope Franklin.”

Tyson attended the film’s Los Angeles premier on Feb. 10 at the Pan African Film and Arts Festival with his father and sister.

“[Blood] is a more human, accurate history,” Tyson said of the final product. “I’m real proud of it.”

Despite “great victories” that have been won since the events of the film, Tyson sees racial issues that still need to be addressed in contemporary North Carolina.

“The way people change the world is messy and complicated,” Tyson said. “It’s not about individual heroism, it’s about how communities respond.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.