Caricature as a means of political commentary is nothing new—although in the 17th century, the most culturally relevant way to assail someone’s leadership ability was to depict him as a personified pear. The Nasher’s newest exhibition, Lines of Attack: Conflicts in Caricature, presents an interesting collection of historical prints alongside their more modern incarnations. The older artwork shows responses to French monarch Louis-Philippe’s reign from 1830 to 1848, while newer works in the field lance critiques at the recent presidencies of Clinton, Bush, and—refreshingly, yet fleetingly—Obama.

The effect of showing the two eras of commentary side-by-side is an understanding of enduring political critique. From the midst of the variation emerges intriguing patterns of criticism: the use of metaphor and references to famous artworks, emphasized by the exhibition’s intentional organization.

The investigation of metaphor provides one of the strongest platforms for the appreciation of the historical works, which may have otherwise receded into the background when viewed next to hyper-vivid and more immediately comprehensible contemporary pieces. Where modern discourse paints inadequate leaders as primates or infants, Daumier’s works from the 1830s cast the much-lampooned Louis-Philippe as a giant pear.

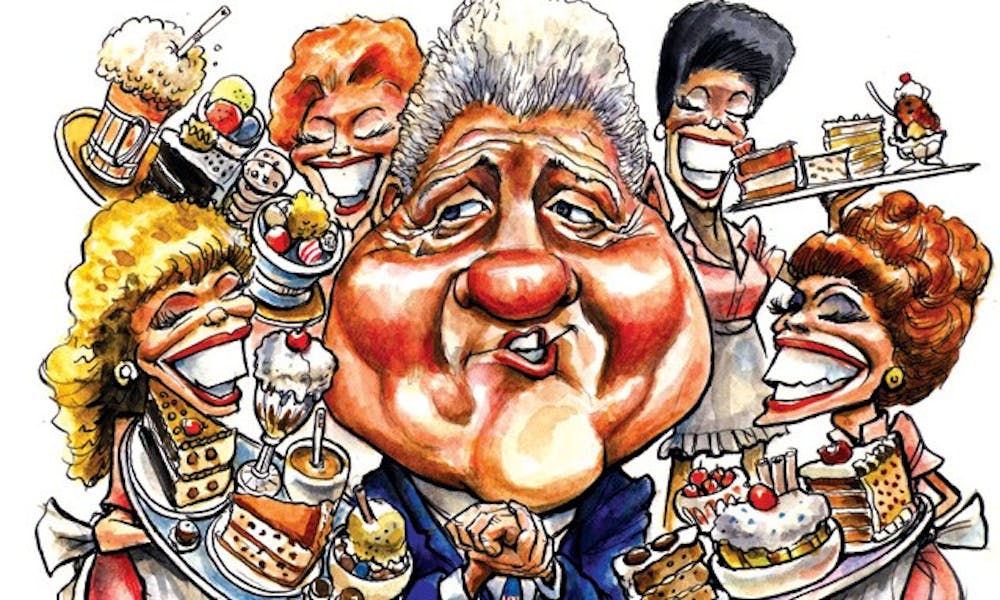

One work shows an immense and corpulent fruit, festooned in royal garb, using an ermine-lined cloak to obscure the bribery and violence that are the subject of the critique. The repeated association of Louis-Philippe with the pear works to highlight the still-notable process by which effctive caricature reduces political figures to symbols of their failures, such that any depiction of politicians becomes rife with subtext. Displayed beside the historical works, images of a pant-less Clinton and an infantile Bush acquire new meaning.

Contemporary caricature obtains fresh validity in the gallery context, as commissioned magazine covers gain surprising complexity when seen in person. For example, Lynn Randolph’s “The Coronation of Saint George” is a large-format oil painting, depicting a sanctified Bush in an artfully draped American flag. His Cabinet members flutter around his head on demon wings, while images of Abu Ghraib and flag-covered coffins frame the central figure. The painting is accompanied by its published counterpart, which served as the cover of The Nation, and the effective difference between the page-sized version and the original work is striking.

Similarly rewarding in their original format are the works of Liz Lomax, who sculpts her figures out of Sculpey clay before photographing and digitally altering them to produce high-resolution prints. Like Randolph’s work, Lomax’s gains immeasurable vitality in the gallery, where her sculptures provide a compelling example of new media techniques. It is in this sense that Lines of Attack forms its most interesting takeaway effect; the exhibition succeeds at instilling an increased respect of the craftsmanship behind the printed images that assail and shape our everyday conceptions of political figures.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.