Professor James Boyle can fly.

Boyle is the William Neal Reynolds Professor of Law and a co-founder of the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain, which supports scholarship and research in the field of intellectual property Primarily, Boyle studies the ramifications of copyright law on the ideas, writings, films, music and other forms of creativity it governs.

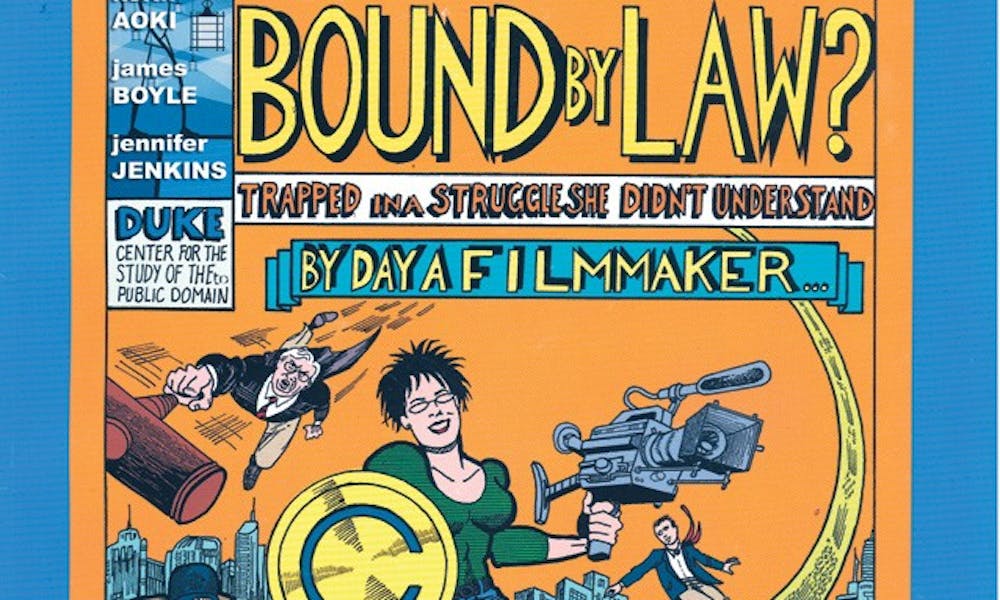

The comic book “Bound by Law?”—which he keeps in tow—features Boyle’s cartoon doppelganger descending from the sky, riding an orange surfboard labeled “Google.” The cover is a busy scene: the Law School prof is accompanied by a faux-Superman judge brandishing a gavel, a jowly Michael Moore in trademark baseball cap, and the book’s spiky-haired protagonist wielding her camera like an assault rifle. Its title and epithet “By night she fought for FAIR USE!” point toward the battle between private interest and public good that the authors have rendered as the latest episode of David and Goliath.

“Bound by Law?”, co-written alongside artist and UC-Davis law professor Keith Aoki and Center Director Jennifer Jenkins, is one weapon in the campaign that Boyle plays a major role in: to broaden the public domain they believe is now being suffocated by America’s extensive copyright laws. “Bound” seems to be Boyle’s own effort at advancing a collaborative artistry, an informational and entertaining piece that provides a moralistic, animated translation of a complex legal issue. “Bound” and Boyle’s latest work, a book entitled simply “The Public Domain,” were published both for sale in print and for free online—a gesture made in the spirit of the books’ arguments.

In “The Public Domain,” Boyle addresses the problems he sees with today’s intellectual property laws.

“I am not saying copyright is bad. I actually think copyright’s a pretty good system. The basic principle [that] you only own the expression, [but] the facts and ideas can be used by anyone—that’s a pretty good line to draw,” Boyle said. “It’s just that we’ve expanded it in every dimension: how long it is, how much it covers, how fine it goes…. All I’m arguing for is a balance between what’s protected and the public domain, and I’m saying, we’ve forgotten the balance.”

What might initially seem to be an abstract issue reserved for ivory-tower legal scholars actually has taken a major role in the life of anyone who consumes or produces American media. Copyright’s influence is a plastic surgeon sculpting the face of hip-hop. It’s the black screen you see every time a Youtube video is taken down, the wasted potential of the Internet not filled as it could be by countless books, movies and films.

And even those works that are accessible are still restricted in many ways. Thousands of adaptations, mash-ups and other methods of making old art new must remain mere concepts, impractical because reimagining often breaks the law.

In the early 20th century, the United States granted a 28-year copyright ownership term for a produced work to its author and publisher, with the option of a 28-year renewal. Although 93 percent of copyrights on books went unrenewed by their authors—their commercial viability usually exhausted after 28 years—media interests and their advocates extended copyright duration to life plus 50 years in 1976 and plus 70 years in 1998.

Boyle explains the thinking behind the policy change as a somewhat confused take on artistic expression.

“Property equals innovation, more property equals more innovation,” he said. “If copyright is at this level and we get this many songs, clearly if it’s at this level we’ll get this many songs! False.” Instead, what’s happened is that the only locatable versions of countless older works—books that have gone out of print, movies that have never been copied, music that hasn’t been digitized—are in the country’s great libraries. The original copies are in some cases literally crumbling into dust, but little can be done because the copyright owners have disappeared into history or anonymity. Without their permission, the works cannot be reproduced or reworked.

“Ultimately, [current laws] put a price tag on information,” said Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African American Studies and a nationally renowned pop culture critic. “Of course, the more obscure information is, the more value there is to it economically. So I think in that kind of environment, it makes it difficult for folks who don’t have monetary access to information or institutional access to information.”

Not only does intellectual property law impact works that have already been made, but it also influences how today’s artists create. Hip-hop is one of the best examples of this tension. At the inception of modern rap, acts like Public Enemy made their beats into what Boyle calls “dense wall[s] of sound, in some cases [using] thousands of samples.” Now, with broader intellectual property laws, utilizing even one sample can be prohibitively expensive and even sometimes impossible.

“You have artists who have been forced to be much more creative, both in terms of copyrighted material that they use and the amount of it they use, and also in trying to find other things that are outside the province of copyright law,” Neal said. “But by the same token, there are artists who do have the kind of institutional affiliation—major labels—that actually allows them to use copyrighted material out front and publicly, but also to do very creative things with it.”

Had these laws always been around, jazz, soul, Walt Disney’s fantasies and even Shakespeare’s style of writing—which all involve building upon other people’s works to create new ones—might not have been allowed to exist. Boyle pointed out that although the judicial system is inclined to protect jazz, to which judges may be more likely to listen, they don’t extend the same protections to rap.

“The question isn’t whether or not you should like today’s rap, the question is whether or not your generation should have the freedom that every other generation had: to use tiny fragments of the culture around them,” Boyle said. “To comment on it, to ornament it, to build on it.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.