In his play Picasso’s Closet, distinguished Ariel Dorfman asks, “Can you continue to produce things of beauty as if people were not dying all around you?”

In conjunction with the Nasher’s current Picasso and the Allure of Language exhibit, Dorfman’s play examines this artistic dilemma.

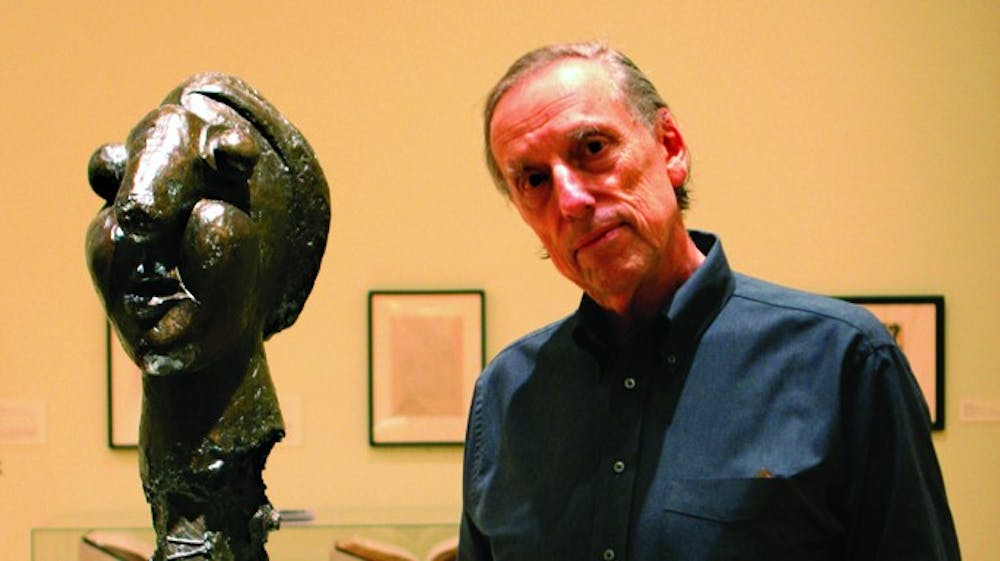

Picasso’s Closet made its debut in 2006 at Theater J in Washington, D.C. and will be performed at Duke as a staged reading directed by Jay O’Berski, a lecturing fellow in the theater studies department. The reading marks the first official event in the Duke University’s Center for International Studies’ year-long series, “Ariel Dorfman: 25 Years at Duke University.” Walter Hines Page Research Professor of Literature Dorfman has been a professor of literature and Latin American studies at Duke since 1989 and has written numerous plays, novels, films, essays, poems and articles during his tenure, including his award-winning play Death and a Maiden, made into a film by Roman Polanski.

Picasso’s Closet is set in 1940s Paris, where Nazis litter the streets and Vichy propaganda infiltrates the culture, yet an underground art world continues to thrive. Despite Hitler’s disgust for the modern art he deemed degenerate, revolutionary artist Pablo Picasso was left in peace during the German Occupation. Why? Executing the most famous painter in the world wasn’t exactly a power move. In Picasso’s Closet, however, Dorfman imagines a scenario in which the artist was not able to escape the hands of fascist fate and is instead hunted and killed by a Nazi officer. In this choice to kill off Picasso, Dorfman raises the question of whether the artist’s self-preservation in a time of genocide was not, in fact, a death in itself.

In 1973, Argentinia-born Dorfman was forced to leave his adopted home of Chile after the coup by Gen. Augusto Pinochet that led to the death of President Salvador Allende. Having been a close supporter of Allende, Dorfman fled Chile and spent his first year of political exile in Paris. Thus, Dorfman’s experience in exile was not far removed from that of Picasso, who chose to relocate to Paris permanently in 1936 during the Spanish Civil War.

In writing Picasso’s Closet, Dorfman considered himself a “collaborator” to his protagonist and allowed himself the freedom to “do to Picasso what he did to his women,” he said.

In this sense, Dorfman was able to reinterpret Picasso’s persona in the same way that Picasso manipulated relationships with his lovers and friends in his art. Most notable of these lovers in the play is Dora Maar, the muse of Picasso’s “Weeping Woman” series.

“At the Nasher, we don’t feel that visual art stands alone,” said Wendy Hower Livingston, manager of marketing and communications for the museum. “[In the exhibit,] art historians who have studied Picasso for decades can learn something new about the artist. And with Picasso’s Closet, Ariel examines a side of Picasso that not many people know.”

Although Dorfman’s Picasso is a notably darker take on the modern art legend, his reinvention of the artist is hardly a critique.

“The best homage you can do to a master is not to take him too seriously,” Dorfman said.

And who better to examine through a twisted lens than the father of cubism himself?

Picasso’s Closet will be performed Oct. 29-31 at the Nasher Museum of Art. Tickets are $5. For more information, visit nasher.duke.edu/picasso.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.