On a sleepy Friday afternoon in the Nasher Museum of Art’s main gallery, two Duke students ambled casually through oil paintings and ink drawings along the first wall of “Picasso and the Allure of Language,” a leading-edge exhibition that displays a lifetime of Picasso works underscoring his relationship with the literary community. Looking at the captions before the artwork as if they were cheat-sheets, one of the pair glanced nervously at a cell phone, mumbling, “It’s 4:26. We should go.” And like that, they were gone. A moment later, my BlackBerry vibrated in my back pocket and I paused to attend to it, breaking my concentration on “Dog and Cock,” a pre-war oil Cubist painting of a dog straining for a dead bird lying on a table.

But the older patrons who roamed the gallery, likely Durham-area residents, seemed to experience the exhibition in a far different way than students. Engaged in each work, they drank in the exhibit slowly, tilting their heads and listening intently to audio guides.

The Picasso exhibition is remarkable in both its unconventional approach to Picasso—locating him at the epicenter of a literary and artistic movement in early 20th century Paris—and the works it exhibits, which are primarily from the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery and have never been displayed together. But the exhibition, still in its first month on view at Duke, has not yet seen the level of student interest that Picasso’s name alone should attract. Of 6,022 visitors to the exhibition between Aug. 21 and Sept. 8, 759 visitors—less than 13 percent—were students, including those who visit with a class, Wendy Livingston, manager of marketing and communications at the museum, wrote to me in an e-mail.

Students who have visited the exhibition said they were surprised at how few students they noticed, unsure of an explanation for it. Tickets for the exhibition are free for Duke students, one per valid I.D., Livingston said, and the museum is located at the median of the most frequently traveled commute at the University. “This exhibition is one of the largest that has ever been available at the Nasher, and a lot of classes have tried to incorporate this exhibition into the course work,” said senior Clare Murray, who is a volunteer tour guide at the Nasher and a student in a seminar on Picasso taught by Patricia Leighten, a professor of art, art history and visual studies, who collaborated on the exhibition. “But there isn’t as much student involvement as I would have expected with such a big name…. People are proud that Duke could get a Picasso exhibit, but that hasn’t really translated into students coming to the exhibit.”

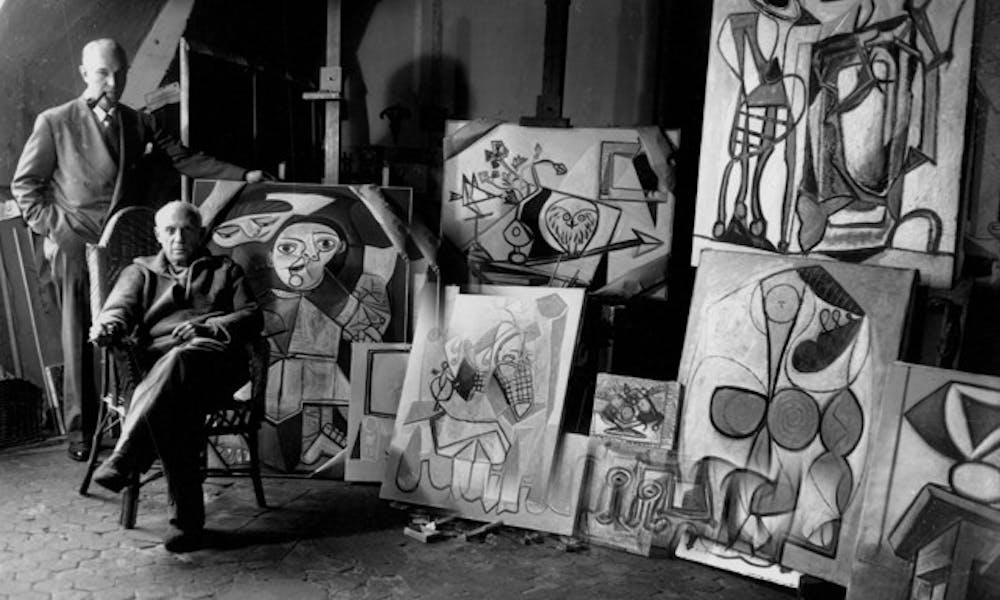

Grown from a scholarly collaboration between curators and art historians at Yale University and Duke, the Picasso exhibition presents a kind of retrospective that examines the legendary artist’s relationships with a clique of luminaries including Gertrude Stein, Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob and Georges Braque. Across the walls of the Nasher, a rich array of media—from ink drawings to illustrated and hand-written texts to oil canvases—chart Picasso’s stylistic evolution from 1900, with an emphasis on his experimental fascination with authors and the written word.

Exhibitions typically show Picasso as influential, but not himself influenced, a standalone giant of sorts, Leighten told me. “The view for a long time has been that he is a galvanic creative force who is only interested in his own feelings and emotions and personal experiences—as if political experiences aren’t also personal experiences…. He’s for his own creative purposes isolated, but then also a leader,” said Leighten, whose scholarly research has focused on Picasso and Cubism. “It’s never that simple. Picasso was always very engaged with his historical moment. This exhibit really puts him in the rich context that his art developed in.”

That Picasso should be seen in his historical and political context is an idea Leighten has advocated in her research, and one that she said has been somewhat controversial among Picasso scholars. But when Leighten first met Susan Fisher, with whom she collaborated in designing and analyzing the exhibition, the two discovered they shared that view of the artist. “We found we were speaking the same language. I emphasize the concept of the artist in relation with his or her society, and in history as a part of history. She was already completely sympathetic to that approach,” Leighten said.

The collection of works displayed in the exhibition traveled to Duke from the Yale University Art Gallery and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, with the exception of two Picasso sculptures on loan from the Raymond and Patsy Nasher Collection.

“There are many important works in this collection, and it does represent every single period of Picasso’s career,” Leighten told me. “The idea that one university would have a collection that comprehensive is astonishing.” All of the works have been accumulated at Yale through alumni donations—notably from renowned collectors Walter Bareiss and John Hay Whitney—or, less frequently, through acquisitions, said Fisher, Horace W. Goldsmith Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Yale University Art Gallery and organizer of the exhibition. Important rarities among the exhibition include a 1905 print called “Salomé” and a small 1912 cubist canvas called “Shells on a Piano,” as well as a collaged study for “Les demoiselles d’Avignon,” one of Picasso’s most famous paintings that is now on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Really, the driver for this exhibition was Jock Reynolds, the Henry J. Heinz II Director of the Yale University Art Gallery, who sits on the board at the Nasher Museum and initially suggested the collaboration between Yale and Duke following the Nasher’s opening in 2005. Leighten was then brought on as a collaborator for the exhibition at an early phase, contributing essays to the exhibition catalogue and working with Fisher in planning and crafting analysis on the exhibition. This collaboration of art historians and curators from Yale and Duke was foundational to the exhibition, both Leighten and Fisher said. “For me, it’s just been a really incredible experience to collaborate with another university,” Fisher said. “It would have been a totally different exhibition if I had only done this at Yale.”

In adapting the exhibition to the Nasher, Leighten said Sarah Schroth, Nancy Hanks Senior Curator, preserved many of the same design features Fisher had implemented at the Yale exhibition—including the color scheme and four-part segmentation—but noted one important difference between the two installations: the show looks better at Duke.

“Somehow, everyone seems to agree that it looks better at the Nasher—even Jock Reynolds,” Leighten said. “[The Yale University Art Gallery] is a brutalist building, so its color is gray, whereas ours is much more creamy and our lighting is beautiful, so the works are illuminated in a way that’s just warmer and more welcoming.”

At an Aug. 27 panel for the exhibition hosted by Leighten and Fisher, it was difficult to spot students in the crowd, although the theater was nearly full. Elderly women in floral cardigans populated the seating with their husbands, whose heads sometimes bowed over their chests in brief, accidental repose.

“At first I thought kids weren’t interested in art, or were intimidated by the space, or that they couldn’t necessarily connect to art,” said senior Sophia Davis, co-president of the Nasher Student Advisory Board, a group that plans student-oriented social events at the museum. “We think that students should be more involved. I’ve talked to my friends that don’t go all the time and they’ve said things like, ‘I don’t have time to go,’ or ‘I would love to, but haven’t gotten around to it.’... And that’s one of the other big philosophies of the NSAB—to get students in the door, and have them see that the Nasher is a space students can actually relax in.”

Davis said NSAB is planning a party in October in which the theme will be based on the exhibition. But NSAB’s efforts focus more on encouraging students to enjoy the Nasher in a social context; raising awareness about ongoing exhibitions is a secondary goal. “The NSAB has succeeded in getting people into the Nasher doors and getting them involved in the space, but I have noticed that through personal experience with friends, they think more of the restaurant and the social area than a museum for artwork,” Murray told me.

For students majoring in art history, or participating in the Picasso seminar Leighten leads, awareness of the exhibition is not an issue. But for others, the exhibition may need to be accompanied with heavy, student-targeted marketing to penetrate their agendas.

“The people I’ve talked to about the exhibition are either art history majors and already know that it’s there, or they don’t know about art and don’t know that it’s there,” said senior Ellie Lipsky, who is also enrolled in the Picasso seminar.

“It’s because it’s not part of [students’] normal schedules, that it’s just one of the other hundred things Duke offers that they don’t take advantage of,” Murray said.

Livingston said the museum has already raised awareness of the exhibit in distributing Picasso event postcards to the Bryan Center and academic departments around campus, and has displayed five large Picasso banners on the street and building itself. Upcoming marketing includes newspaper and magazine ads and Picasso-related Facebook events, Livingston noted. “The museum is working to attract Duke students to the exhibition,” she said.

And the exhibition should hold appeal for today’s student, once they get through the museum’s doors. That the body of work is modern art means each work is open to interpretation, manipulation and revision—the student has a chance for intellectual engagement, even without any pre-existing knowledge of the artist. There is a distilled bohemian spirit that runs through the exhibit, too, smacking of youth and experimentation.

Among art history students at Duke and at Yale, Leighten and Fisher said the responses to the exhibition had been immediate and enthusiastic.

“The students that I know at Yale all seemed very excited that it was this new take on Picasso, a different look at him,” Fisher said. “They thought Picasso was cool, I think he seemed very relevant to them. The relationship of text and image, the complications between the two, and the way that he blurs lines between writing and drawing and painting intrigued them.”

After all, the idea itself for the exhibition sprung from students’ mouths—Fisher said a group of students in her seminar at Yale, credited in the exhibition’s catalogue, were the first to fixate on Picasso’s relationship with the literary community in the early 20th century. “I taught an undergraduate seminar in 2006, and it was at the same time that I was going through the Picasso materials,” Fisher said. “I was struck by how a number of them actually discussed language in their papers. It seemed to be a topic that people were interested in. I was thinking about it, and the students were, as well.”

It is apparent that “Picasso and the Allure of Language” has met with the early success it deserves in attracting locals and those students most interested in Picasso’s work to the show. But what remains to be seen is whether the show’s language is alluring enough to draw, Siren-like, even the most art-apathetic of students to the Nasher’s grounds.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.