In honor of Duke’s Centennial, The Chronicle is highlighting pivotal figures and events throughout the University’s history. Here we take a look at Joseph Maytubby, Trinity College’s first Native American graduate:

Although Duke’s Native American Studies Initiative is just beginning to gain its footing after being established last year, the University’s connection to Native American students traces back to long before it was officially chartered.

Trinity College enrolled its first Indigenous students in the 1880s, but they remained separated from the rest of the student body and did not receive standard Trinity degrees.

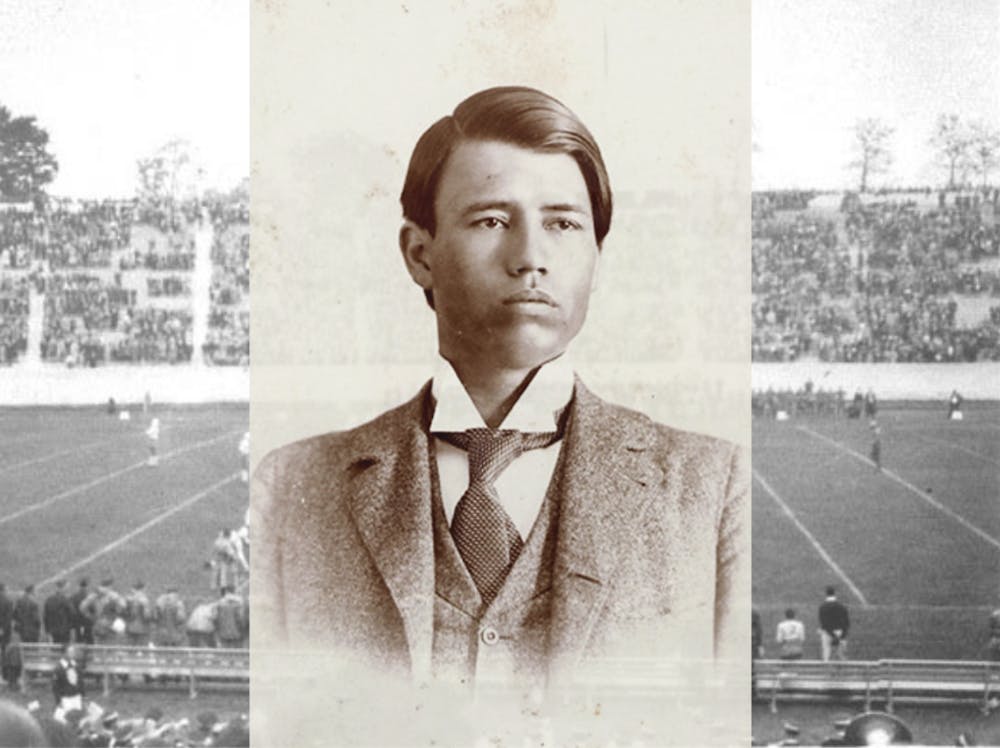

The school’s first official graduate, Joseph Maytubby, joined as part of the Trinity’s first Durham-based class. He went on to become one of the institution’s most celebrated students, renowned for his leadership in the classroom and on the field.

Maytubby was born in the late 19th century in the village of Goodland, then located in the Choctaw Nation but today near the town of Hugo, Oklahoma. He was not Choctaw himself, but rather a member of the Chickasaw Nation born to a Chickasaw father and white mother.

Sources disagree on his birth date, but it was likely between the years of 1868 and 1870. According to historian Joseph Thoburn, Maytubby’s parents died when he was still a young child, which contributed to gaps in the record of his early life.

He attended Chickasaw Nation schools including the Wapanucka Institute, also referred to as the Rock Academy. The school, named Wapanucka Female Manual Labor School, opened in 1852 but soon closed in 1860, serving as a Confederate hospital and prison during the Civil War. It reopened as a school for male and female students soon after the war ended.

At the time Maytubby was in attendance, the Wapanucka Institute was operated by Trinity College alumnus James Scarborough. In 1889, Scarborough wrote to Trinity President John Crowell advocating for some of his Chickasaw students to be accepted into the college.

“I have seen the superintendent of the [Chickasaw] Nation in regard to sending students to Trinity, as the nation pays the college expenses when her young men go,” he wrote. “… We have some very fine students here but more who are now ready for Trinity.”

Trinity College had enrolled its first Native American students in 1882, 20 boys from the eastern band of the Cherokee Nation in North Carolina. The college’s decision was largely assumed to be financially motivated, as it had faced a series of funding shortages but received payment from the federal government to educate Native American students.

The “Cherokee Industrial School,” which was operated by Trinity but kept separate from its other students, was later criticized for westernizing its Native American students, forcing them to stop speaking their native language as part of the assimilation process. It was named in a 2022 investigative report by the Department of the Interior that identified over 400 such boarding schools across the nation.

The school was only in operation for a few years, as then-President Braxton Craven — who enrolled the Cherokee students — died later that year. Trinity’s trustees transferred responsibility for their “care and training” to Craven’s son and shifted around the administration multiple times before the school was abandoned altogether a few years later.

Soon after in 1892, Maytubby enrolled as a student at Trinity. It was the first year the school operated in Durham, as it had previously been located in Randolph County, North Carolina.

Maytubby was a model student and a gifted public speaker. He was widely recognized for his strong oratory skills, receiving the top prize in a Freshman Declamation contest and a sophomore speaking contest. His achievements were reported in newspapers as far away as California and Montana, though many of the articles featured Native American stereotypes.

Maytubby served as president of the Hesperian Literary Society and managed a section of the Trinity Archive literary magazine. He was elected president of the junior class in October 1894.

Outside of his studies, Maytubby also played on Trinity’s fledgling football team, which was started in 1888 by President John Crowell. The left halfback scored the only touchdown in the Blue and Whites’ 6-4 win over rival North Carolina in October 1893 and was frequently praised for his performance throughout the rest of the season.

In November 1894, Maytubby was elected captain of the 1895 football team by his teammates — but just one month later, new President John Kilgo banned intercollegiate football at the school.

Despite reports as close to the season’s start as September that “Captain Maytubby [was] getting his material in shape and [said] he [would] have a good lightweight team,” Kilgo moved to end the program before the 1985 squad could play any games, labeling the sport as “too dangerous” at the time. However, in an interview with the Raleigh News and Observer, he argued that “these games tend to disorganize intercollegiate sympathies,” “engender feelings of rivalry and strife among students of the various colleges,” “cause an unnecessary expenditure of money” and “take time from the studies.”

Trinity’s players would not be seen on the gridiron again until 1920.

In 1896, Maytubby was among 24 students in Trinity’s first graduating class from its Durham campus. In addition to receiving a Bachelor of Philosophy degree, he was honored with the Wiley Gray Medal for best commencement speech in his class.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Despite having only five games under his belt before the demise of Trinity’s football program, Maytubby’s prowess on the field made him a prime target for recruiters at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and beyond. Following his graduation from Trinity, the college’s first Native American graduate enrolled in the University of Texas’ department of law in the fall of 1896 to play for the Longhorns.

Maytubby did well as a halfback and fullback in the nascent program’s first game of the year, then only in its fourth-ever season. His performance was lauded later on in the year as “steady and brilliant,” and he succeeded in defining himself as one of the roster’s “distinctive stars.”

Though he played only one season at Texas, Maytubby would be remembered as “one of the best football players [the program] ever had.”

It is unclear whether he ever received a law degree from the university, but by 1897, Maytubby had returned to his home state of Oklahoma and was practicing law in the town of Tishomingo, capital of the Chickasaw Nation.

His career from then on was anything but static.

Back home in the Chickasaw Nation, Maytubby served as superintendent of schools for a year, then moving in 1899 to the position of auditor of public accounts. In 1901, the city of Tishomingo was officially incorporated, and he was elected its inaugural mayor.

He retired from practicing law in 1905, working from then on as a farmer, horse rancher and cotton gin operator.

Maytubby married Abigail Theodosia Kemp in 1903. They had two children together, though one died as an infant and the other later died in a car accident as a young adult while both parents were still alive.

He died Aug. 18, 1957, at around age 89, and his funeral service was held at the Clarita Methodist Church, where he had been a member for 40 years.

Zoe Kolenovsky is a Trinity junior and news editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.