The cost of an undergraduate education has risen annually for at least the past 10 years, a trend administrators said is necessary as the University invests in better programs and initiatives.

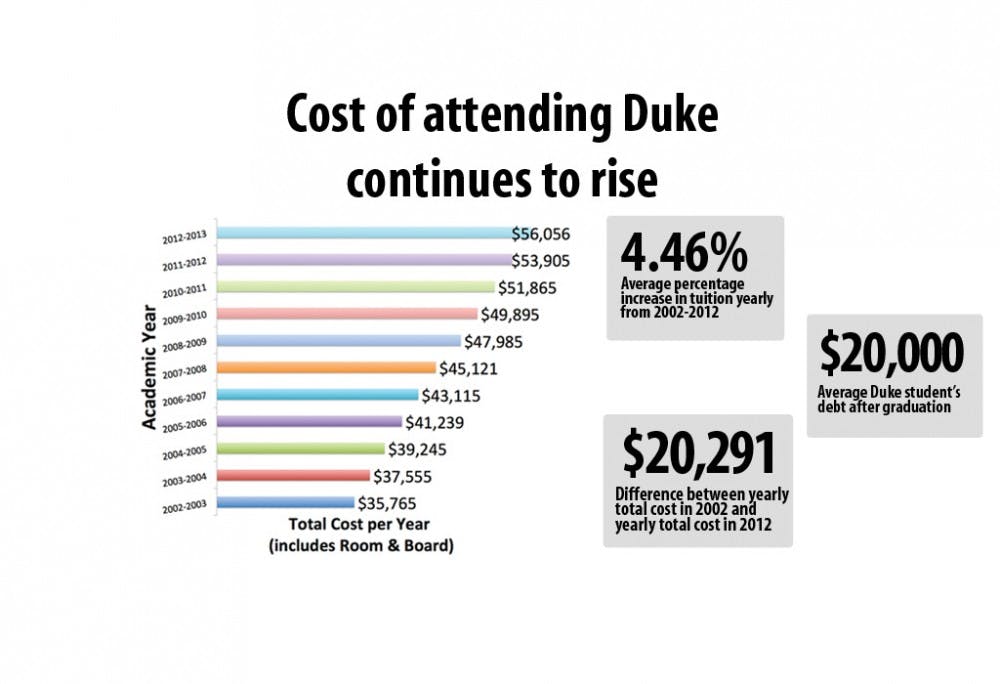

Undergraduate tuition has increased more than 50 percent in the last decade, from $27,844 in 2002-2003 to $42,308 in the coming academic year. When considering the total cost of attending Duke, the University’s price tag topped $50,000 for the first time in 2010-2011 and will reach $56,056 for the 2012-13 school year. As the price rises, the administration has prioritized funding for financial aid to keep pace with increases in student need.

The tuition increases reflect how the costs to operate a university of Duke’s caliber have increased, especially for energy, salaries and technological improvements, said Michael Schoenfeld, vice president of public relations and government affairs. This reflects a nationwide trend of college tuition increasing faster than inflation—even faster than inflation in the health care sector.

“You’re at Duke and you look around, and you see all the different pieces that have to come together to create a university like this,” he said. “[Tuition pays for] everything from faculty salaries to maintaining facilities to compliance with regulations to health insurance to maintaining grounds to building parking lots.”

The $50,000 mark is just one in a series of thresholds that higher education has passed in the last several decades, Schoenfeld noted.

“[In the 1980s], the total cost of Duke crossed the $10,000 barrier and at the time, that was a huge deal: ‘Oh my gosh, the cost of a private college is $10,000 a year,’” he said.

Even in sectors such as technology, where costs to the individual consumers typically decrease over time, the University incurs huge capital costs of up to hundreds of millions of dollars in its effort to implement upgrades across campus, Schoenfeld added.

Questionable costs

But these investments in infrastructure and facilities do not necessarily contribute to a better-quality education, said George Leef, director of research at the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy, a think tank based in North Carolina.

“The more money you spend, on faculty, on library facilities, on a range of things, the more prestigious your institution looks,” Leef said. “What we get is this arms race on spending on things that don’t have anything to do with educating students but make the institution look more prestigious.... It’s not making undergraduate education any better, just more expensive.”

Other critics of the cost spiral in higher education, including former Secretary of Education William Bennett, have pointed to the increased availability of federal financial aid as a direct cause of rising tuition costs at universities.

In recent years, however, Duke has become less dependent on federal sources of financial aid and relied more on its own forms of grant aid through private donors, said James Roberts, executive vice provost for finance and administration.

“Most of our financial aid is financed by Duke, so it’s not like we’re riding a huge source of federal funding,” Roberts said. “We appreciate it, but it is a relatively small percentage and a much smaller percentage than it was a decade or two ago. So it’s really not a plausible argument to suggest we’re raising tuition because of that federal financial aid.”

Approximately 80 percent of financial aid dollars come from University funds, noted Alison Rabil, assistant vice provost and director of financial aid.

The typical annual increase in tuition, hovering at about 4 to 5 percent in the last 10 years, is usually offset by the University’s grant aid system, which increases by at least the same amount to make up for the extra cost of tuition to individual students who are already receiving grant aid, Rabil said.

“At one level, you could see it as Duke paying itself back, but the way that we account for things it is definitely a real cost as well,” Schoenfeld said.

Maintaining financial aid

One of the principle goals of the Board of Trustees in setting tuition rates is to keep the amount of funds available for the University’s private financial aid greater than the increase in tuition, Schoenfeld said.

Roberts noted that a cap is never placed in advance on how much financial aid will be awarded to students given its need-blind admissions policy and commitment to meet each student’s demonstrated financial aid fully.

“[Financial aid] is a priority for the school,” Rabil said. “Lots of budgets got cut for the past few years, but the financial aid budget didn’t get cut. We’ve tried to make sure that as the economy got worse, families were still able to afford an education at Duke.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

At the University, 55 percent of undergraduates receive some form of financial aid, including need-based, athletic and merit aid, Rabil said. Of those students, 93 percent receive need-based aid,

The University has made a concerted effort to reduce the number of loans in students’ financial aid packages. In the 2002-2003 school year, the University spent $37 million on student financial aid.

For the 2011-2012 academic year, the University expects to spend a total of $120.5 million of institutional funds for undergraduate financial aid, according to a Duke news release Feb. 24.

The biggest effect on families paying for their children’s education at Duke has not been the tuition increase but instead the bad economy, Rabil noted.

“Did a family member lose their job? If a family member lost their job, their financial aid will go up significantly not only to cover the cost of tuition but also to make up for that job loss,” she said.

The average student who does take on loans graduates with about $20,000 in debt, Schoenfeld said.

“While that is significant for sure, when you think about the value of the investment, it’s just important to put that in perspective, that it is an investment in education that will last a lifetime,” he said. “Some people don’t think twice about paying that for a car.”

Although a larger amount of grant aid comes from the Duke University Endowment, a significant percentage still comes out of the general operating budget, Schoenfeld said. Adding funds for financial aid to the endowment is a top priority for Duke’s future fundraising, he added, since doing so will free up funds in the general operating budget for other University initiatives.

Although tuition has increased by roughly the same percentage each year for the past 10 years, each year’s increase is not assumed to be the same in advance, Schoenfeld noted.

The Office of the Provost gathers recommendations from the deans of each school and presents a tuition recommendation to the Business and Finance Committee of the Board of Trustees each year, which is then put to vote and usually passed by the Board. The provost’s office meets with students from the Graduate and Professional Students Council and Duke Student Government to get feedback on the recommendation beforehand, Roberts noted.

Even with the growth of tuition over the years, students who pay full price are still receiving a subsidy because a full tuition payment covers about two-thirds of the cost of Duke undergraduate education, Schoenfeld noted. The cost of education for all students is partially covered through the University’s endowment.