Editor’s note: This is the first article of a three-part series focusing on the extent of transparency surrounding the Duke’s Board of Trustees. Today’s article takes a look at the Board’s decision under former President Terry Sanford to open Board meetings. Wednesday, The Chronicle turns the focus to the current relationship between the media and Trustees and explains why the Board decided to limit access. Thursday, The Chronicle details recent developments, including the outlook for access moving forward.

Days before the Board of Trustees’ spring 1971 meeting, then-President Terry Sanford announced that the governing body would continue to meet behind closed doors.

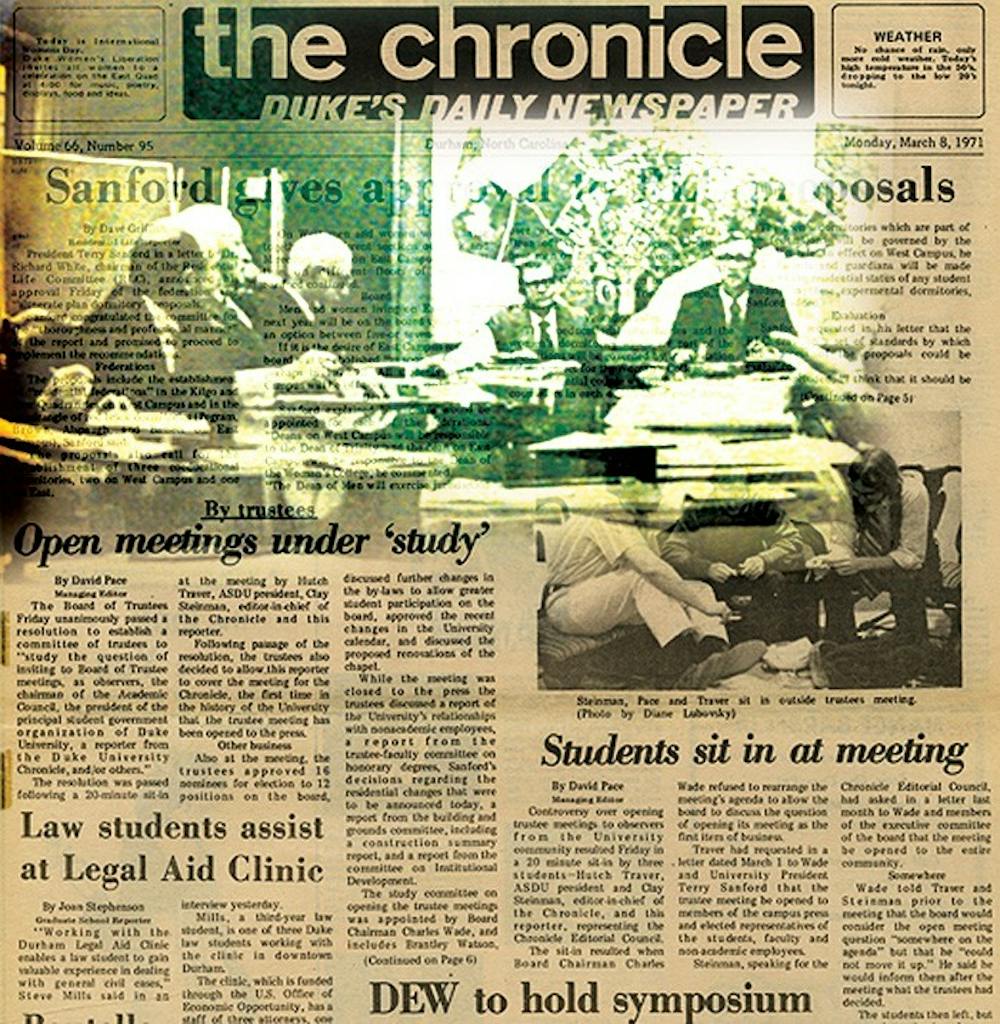

This decision could have been the end of a joint effort between the student government and The Chronicle to open the quarterly meetings that shape the University’s future. But two years after students demanded racial equality by entering Duke’s main administrative building, the student leaders were not so easily dismissed. Chronicle staff met to send Editor Clay Steinman, Trinity ’71, with the student body president to protest at the meeting after the Board refused to put the students’ request as the first item on the agenda. Then-Chronicle Managing Editor David Pace accompanied to report the sit-in.

“We didn’t go into this assuming that Sanford would break down,” Steinman said in a recent interview. “We had no idea what was going to happen. I mean, I was scared s—less.”

The Board has the ultimate authority to make major decisions for the University, ranging from hiring a president to setting tuition to approving new construction. At a private institution like Duke, Trustees are not required by law to meet in public or produce internal documents as they might at a public university.

The Trustees filed into the boardroom to start their meeting, but the three students refused to leave until Board members agreed to discuss media access and transparency.

“We did not come here to disrupt your meeting,” said then-Student Body President Hutch Traver, Trinity ’71. “The Trustees are the governing body of the University, and, as members of the University community, we have a right to observe your meeting.”

In general, the Trustees were “very cordial” to the students, Pace, Pratt ’71, wrote in the next Monday’s Chronicle. Some Board members voiced their opposition, however. One turned to Traver and reminded him, “The Trustees still run this University, boy.” Sanford grabbed Traver’s arm and told the three students to come to his office. Freeing himself, Traver told the reportedly shaken president, “You better watch out—you’re about to blow your liberal cool.”

Sanford, who was governor of North Carolina from 1961 to 1965, restored order. After talking with the Trustees, Sanford allowed Pace to be the first reporter to ever cover a Board meeting, and the body passed a resolution to study the possibility of increasing transparency.

A few months later, the Trustees voted unanimously to open Board meetings to invited faculty, students and reporters.

“There were things happening [in those meetings] that were directly affecting the lives of students in the community,” Pace said. “We felt like we had a right to be there and observe the decision-making process that led to these things and report on it.”

An open era

When Sanford began his presidency, the University was ready to incorporate more voices into its policymaking. Duke had just completed a review of the school’s decision-making processes, and one of its recommendations was to increase student input, a reflection of campus concerns at the time. Sanford brought a willing attitude, said Allison Haltom, Woman’s College ’72, who served as university secretary under Sanford’s three successors. She credited the “very open atmosphere with respect to the press” to his experience with North Carolina’s open government laws.

In a December interview, current President Richard Brodhead said it is worth remembering the historical moment in which these events took place. Sanford was a true politician, he noted, familiar with the sort of conflicts that characterized the 1960s.

“What do you think Terry Sanford had seen in his day? Conflict and peacemaking,” Brodhead said.

For the remainder of Sanford’s presidency, Trustees made decisions with University representatives in the room. In the years since, administrators have gradually restricted how much of the process is open to the public. Today, no one without a binding confidentiality agreement is allowed in the room at all.

Despite Steinman’s trepidation, the sit-in worked. Student reporters were present to document the historic meeting in which the Board combined the separate colleges for men and women. Ralph Karpinos, who had succeeded Steinman as editor, covered the meeting with a photographer.

“That was pretty monumental,” Karpinos, Trinity ’72, said in a recent interview.

Although Board meetings were open, some continued to criticize lingering secrecy. The Trustees reserved the right to break into private sessions to discuss confidential matters, such as faculty salaries and honorary degree recipients. Pace said at the time that the Board only allowed the media to hear what the Trustees wanted to make public and continued to make important decisions in private.

The change under Sanford nonetheless allowed the Duke community to have conversations about major issues before the Trustees made their final decisions. Steinman, who has worked in higher education for 35 years, said he still considers Sanford to be a model for how an administrator should interact with the community.

“I can’t tell you how much the school changed from when I got there in ’67 to what it was like in ’71,” Steinman said. “The times were different.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.