On a winter night in Raleigh, a man wearing khakis, a red sweater vest, a tweed jacket and a tan cap steps up to the pulpit. “Brothers and sisters,” he addresses his congregation, “in the beginning was the word.” He pauses, the crowd hanging onto his every word . He continues: “And the word was with God, and the word was God.” His audience sits on plastic white chairs and wooden benches. The speaker is Allan Gurganus, one of several writers who have come to “testify” on behalf of the Quail Ridge Books and Music store for its 28th anniversary celebration.

The primary object of their praise is bookstore owner Nancy Olson, who opened the store with her husband in 1984 with little bookselling or retail experience with the exception of a nationwide tour of 24 bookstores.

As writer Jill McCorkle recalls when she takes the podium, she met Olson at a Southeast Booksellers Association convention when she was about “this green”—here she taps the forest-green wall behind her—where Olson asked McCorkle if she would like to read her pieces at the store. (“I’ve heard sometimes bookstores have writers come to read,” Olson had said).

In addition to sharing stories about Olson, speakers fawn over the store itself, calling it a “democratic space,” a “sanctuary” and “the heartbeat of the community.” After each writer speaks, Olson returns to center-stage and with a look of mock conceit, says, “wasn’t that wonderful,” before promoting the speaker’s upcoming book. She is wearing a purple shirt with white lettering that reads, “All’s Quail that Ends Quail,” over a white turtleneck that matches her short hair.

At the end of the night, guests mingle around punch and two cakes sculpted like open books. As indicated by the speeches, the event is more than a celebration. It is a call for the preservation of the store—and by extension—of all independent bookstores. It’s no secret that the independent bookstore business has been shrinking. As today’s readers increasingly make the switch to e-books, about 200 independents a year find themselves going out of business, according to the American Booksellers Association.

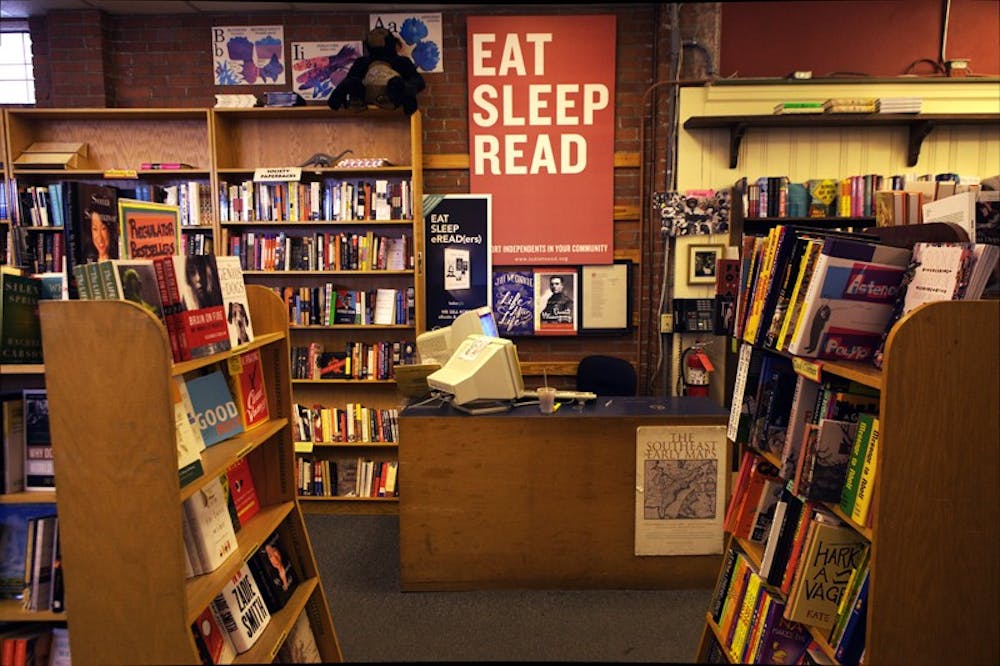

Bookstores in the Triangle region have managed to stay afloat, but they haven’t escaped this trend altogether. The Regulator Bookshop in Durham has consolidated books in the upstairs portion of the store (arranging the same inventory with more books spine out than face out) and rented out part of its basement to a clothing store. Chapel Hill’s Flyleaf Books has added a used books section and is selling more non-book items, like jewelry.

“All the independents are trying to figure out what they can do, focus more on events, focus more on what makes them a community space,” says Land Arnold, a co-owner of Flyleaf.

Over at Flyleaf, the books lining the shelves are flagged with dozens of recommendations handwritten by the staff. Some employees have gained loyal followers, Arnold says. In the age of the e-book, bookstore owners like Arnold are reminding customers of what they can offer that chains and websites can’t.

As Quail Ridge store manager Sarah Goddin puts it, “It’s not so much the book itself. It is the sense of community and having a place you can discover things and interact with other people.”

When compared to money spent online or at chains, a higher percentage of money spent at local stores stays in the community. The Regulator boasts a 45 percent return of revenue to Durham, in contrast with a 13 percent return for chains and a 0 percent return for online purchases, according to the store’s website.

The main reason for this difference is that unlike chains, local businesses buy many supplies and services from local businesses, according to a 2009 study conducted by Civic Economics. Economists at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance have also suggested that money spent at local businesses circulates more quickly, and as a result a greater number of people profit. Also, because independent stores tend to have lower profits than chains, the majority of their revenue goes toward paying for salaries and supplies (which are often bought locally).

This is a less romantic, but justifiable, reason to frequent the independents, which tend to be loved for their idiosyncrasies, like the nook with the typewriter at Shakespeare and Co. in Paris or the 18 Miles of Books at the Strand in New York. Yet the nature of independent bookstores is good for more than just added quirk. They give each store manager a freedom in choosing titles that chains don’t have—a trait that Quail Ridge displays in its office. On the door is a bumper sticker that reads, “A PBS mind in a Fox News world.” On the wall, hanging beside family pictures and various posters, including one for “Cold Mountain,” there is a poster that reads, “Books: They have been beaten and burned, drowned, tortured, imprisoned, suppressed, executed, exiled . . .”

It is here that Goddin, a petite woman wearing a pale blue sweater, recounts the story of one controversial novel. When Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses” was first released, stores selling the book in London and California were bombed. Various American bookstore chains, including Walden Books and B. Dalton, decided not to sell the novel, citing the need to protect their employees. No Walden Books manager would have been able to sell the novel even if she had wanted to. Many independent bookstore owners, on the other hand, made the risky decision to do just that. In his memoir “Joseph Anton,” released this September, Rushdie publicly thanked independent bookstores.

In response to recent profit-cutting trends, independents are considering significant changes to their business models, including the introduction of on-demand printing by way of Espresso Book Machines, which can be used to print personalized versions of books in print, self-published titles and works with expired copyrights.

But EBMs don’t come cheap. In addition to the machine’s cost, the amount of space it would require and the time needed to train employees are deterrents to purchasing one, says Tom Campbell, co-owner of The Regulator. Arnold seconds this sentiment. “We can’t attempt things at this moment that won’t be at least in the short future profitable.”

Goddin has observed the process of N.C. State’s EBM, but says that she’s not yet convinced it would be enough of a hit with the general public to justify installing one in the store. However daunting it might be for an individual store to install an EBM, it could “be a neat thing for local area stores [including Flyleaf and Quail Ridge Books] to maybe go together on,” Campbell notes.

Still, the machine is a print-based solution to a largely Internet-driven problem.

Recently, independents have started stepping up their online presence. Quail Ridge encouraged customers to tweet reasons they value the store, and awarded a $25-gift card to one of those tweeters at its 28th anniversary celebration. The store also has an Affiliate Program through which store supporters can link their websites to the bookstore’s website free of charge, and then receive a commission for each sale made. Currently the program only has 15 to 20 members, Goddin estimates. She slips in the fact that Amazon had a similar affiliates program, but when the North Carolina Legislature announced its plans to charge a sales tax to Amazon for North Carolina affiliates, the company dismissed them. Flyleaf, which has a similar program, “[doesn’t] get much traction from that really,” Arnold says. Even if more focus is put on online sales of physical books, it’s the online sales of e-books that really make a difference.

A Harris Interactive poll conducted in March 2012 indicated that almost a third of American adults use an e-reader or a tablet. This percentage has nearly doubled since 2011, while print sales have declined. E-books became the primary format for adult fiction in 2011.

Well aware of these trends, independents are carving out their own share of the e-book market. The American Booksellers Association, which seeks to promote the interests of independently-owned bookstores across the country, recently made a deal with Kobo, a Toronto-based e-book company. Quail Ridge, Flyleaf and The Regulator each began selling the e-reader, which comprises about 3 percent of e-reader sales in the United States, in stores this fall. After buying the Kobo, customers can purchase e-books through the independent bookstore.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

In the Quail Ridge office, Goddin motions to a tote bag at her feet which contains a “Kobo Kit”—according to a handwritten label—that staff use to learn the Kobo system. The e-readers are on display at the cashier station. “I have been sort of anti-e-books, but I have to admit I took the Kobo Glo home, and I really liked it, so I have to eat my words,” Goddin says. Since the store started selling the devices in November, Quail Ridge has sold about 30.

“I think we’re going to be very competitive in selling e-books, and people can get out of the Amazon jail,” Campbell notes.

By “Amazon jail,” Campbell means that Kindle users don’t technically own their books. In 2009, the George Orwell novels “1984” and “Animal Farm” were—ironically—deleted from Kindles by Amazon, which reasoned it had initially purchased the works from an unlicensed vendor.

From their vantage point in the midst of these literary trends, independent booksellers don’t seem convinced that the grip of electronics will last. Arnold says Flyleaf, now in its third year of operation, hasn’t been around long enough to accurately judge the effect of e-books on sales.

“I can see people talking about it constantly, but all the stats show that people who do buy e-books and e-readers also buy physical books still,” Arnold says. “It’s not the category killer that the iPod was to music sales.” He goes on to say that “the dirty secret of the e-book is that it’s not a sustainable model for anyone,” as publishing houses also suffer financially from selling e-books, and that shopping for books online does not provide the same opportunities for “serendipitous discovery” that can be found in a bookstore.

“I think with e-books there is a question, and it hasn’t been fully tested yet, whether [when] you’re reading, and you’re trying to really learn something, are you going to learn as well reading on a screen as you will reading a book?” Campbell says. “We obviously prefer real books, but for people that are reading digitally, we want them to be able to be our customers as well.”

Just as independent bookstores in the Triangle have started to sell e-readers, it seems tablets may be edging them out as the preferred method for e-reading. Arnold attributes Flyleaf’s “underwhelming” Kobo sales to the growing popularity of tablets.

“In fact, half as many e-readers were sold in 2012 as 2011. And this is all e-readers, not just Kobos,” Arnold wrote in an e-mail. “I bought one… and have yet to use it.”

Book Industry Study Group survey revealed that 17 percent of people who do their reading online—and 38 percent of people who buy e-books weekly—use a tablet, and 9.2 percent use a smartphone. Both percentages represent increases from the previous year. These numbers are reflected in a growing number of tablet models. In addition to the iPad and Google Nexus, users will soon be able to choose from Toshiba, Samsung, Lenovo, Dell, HP, Fujitsu, Asus and Acer devices.

Quail Ridge recently began selling the tablet form of the Kobo e-reader, the Kobo Arc. But whether independents will succeed at uniting their traditional model with emerging technologies remains unknown. “I’m not sure they will see their local bookstore as a place to buy [tablets]. We’ll see!” Goddin wrote in an e-mail.

Only time—and readers like you—will tell. By the way, in what format are you reading this article? Independent booksellers might like to know.