The following is the second story in a two-part series that examines the relationship between Duke athletics and Title IX since 1972. Part one reflected on the history of the University’s compliance with Title IX, and part two analyzes how Title IX currently affects the athletic department.

Last year, Duke female freshmen received an email from Julia Domina, then an assistant coach with the rowing program, gauging interest in joining the team.

The rowing team, which was started in 1999 as a part of Duke’s effort to comply with Title IX, boasted 62 female athletes from Oct. 16, 2010-Oct. 15, 2011, the period of the most recently available public data. It is the largest of any female sport, second among all Duke programs only to football and its 109 student-athletes.

Title IX, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, aims to create gender equality on the playing field among its goals.

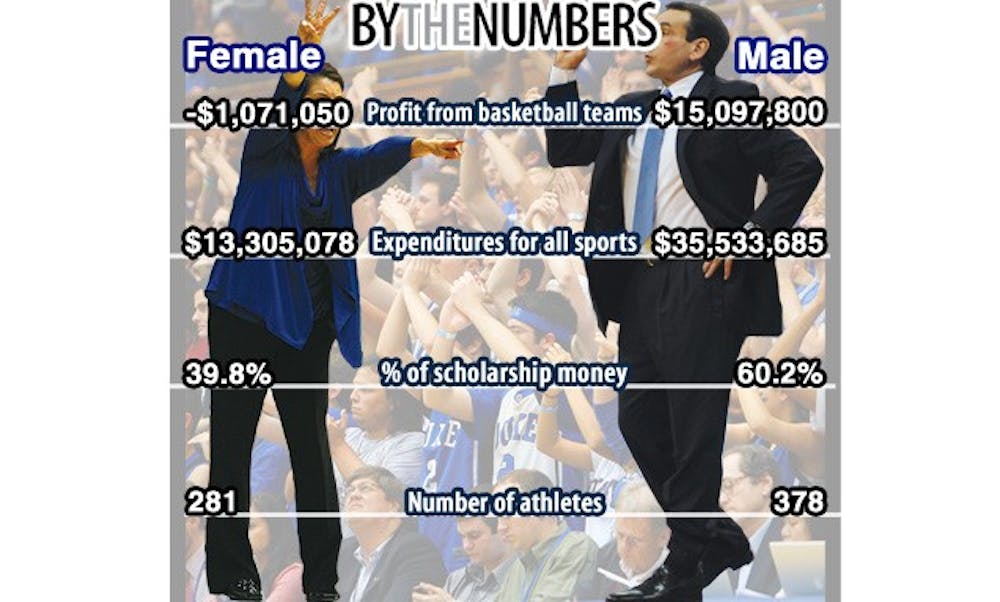

Duke athletics’ financial statements are submitted annually by the University’s compliance coordinator, Deputy Director of Athletics Chris Kennedy, to the Office of Postsecondary Education of the Department of Education. According to the University’s 2010-11 data, the athletic department spent $35,533,685 on men’s teams and $13,305,078 on women’s teams. Over that period, there were 378 male athletes and 281 female athletes.

But, a look at the financial data does not properly reveal the legislation’s influence because a holistic assessment of gender-equality is considered more important than a numbers-based one.

“[We ask] what is it like to be a women’s lacrosse player,” Kennedy said. “Not only compared to men’s lacrosse players, but all other student athletes. And is that experience comparable quantitatively and qualitatively?”

These are financial decisions but also comprehensive examinations of equipment, field time, travel expenses and quality of life for the student-athletes.

Of Duke’s 26 sports, only men’s basketball and football are profitable, earning $15,097,800 and $3,405,764, respectively, in 2010-11. Football and men’s basketball are two of the three “revenue” sports, which according to OPE’s website are ones “in which market forces play a major role in determining compensation levels [for coaches].”

The third “revenue” sport is women’s basketball, which lost $1,071,050 in that span.

According to Duke’s reported numbers—which list the average salary of all women’s head coaches at $150,971 and the average salary of women’s head coaches excluding women’s basketball at $93,069—head coach Joanne P. McCallie earned $729,991 in the last reported year.

The increased financial commitment and competition in women’s basketball was shown when Gail Goestenkors left Duke after the 2007 season, after Texas tempted the coach who had been with the Blue Devils since 1992 with a reported $800,000 annual offer.

Since then, Duke has made strides to retain McCallie, signing her to an extension through the 2016-17 season in Fall 2010.

The athletic department, though, primarily pays attention to the bottom line across all 26 sports. Kennedy, who has been at Duke since 1977, has seen the dramatic effect of the University’s increased investment in women’s sports.

“If you could bring back the 1980 women’s basketball team, as they were then, and put them on the court with our team now, they wouldn’t be able to get the ball across halfcourt,” he said. “The idea that a women’s basketball coach would be making close to a million dollars would have seemed just as likely as flying to Mars by flapping your arms.”

Mitch Moser, the athletic department’s chief financial officer, said that the decision on how to spend money across programs is broadly a consideration of how to best benefit every student-athlete.

“What I try to do from a financial standpoint, and what we as an institution try to do, is to allocate the resources to each and every program so they can be as absolutely successful as they can be,” he said.

Losing money in women’s basketball is not atypical—at least eight ACC schools lose more than Duke—with Virginia hemorrhaging $4,326,443 in their most recent reporting year.

But, reporting methodology is not consistent across every school, or even within an institution. Even at Duke, calculating the data is part of an evolving process that seeks to most accurately pinpoint revenue streams that are non-sport specific.

Income from concessions, sponsorships, merchandise and donations were not previously assigned to specific sports’ revenue calculations, leaving even the men’s basketball team in the red in previous years. But, many Iron Duke donations are used to gain entry to men’s basketball games at Cameron Indoor Stadium, a factor now included in the math.

A major element of the balance sheet is the University’s subsidy of the athletic department, approximately $14.6 million in the 2009-10 fiscal year. That money, according to Kennedy, is specifically earmarked for scholarships to the student-athletes.

In the OPE numbers, $8,761,913 was given to the male athletes in scholarship money while $5,789,419 was given to women, 60.2 percent and 39.8 percent, respectively. Although that is out of proportion with the 57.4 percent and 42.3 percent of male and female athletes at Duke, it fights a difficult balance between NCAA scholarship allotments and how many scholarships a coach chooses to allocate.

Football is given the most scholarships of any sport with 85, and there have been instances in the past, such as with Goestenkors, where a coach does not use all of those available to her. In those cases, the department must find other areas in which gender-equality can be achieved as a part of the school’s all-inclusive vision of complying with Title IX.

“Every sport is unique,” Moser said. “They’re different in scope, they’re different in number of student athletes, they’re different in where they travel, they’re different in how many contests [and] they’re different in the type of equipment they get.”

Other financial decisions weigh the monetary factors and the lifestyle of being a student-athlete. The women’s basketball team often flies to games, as they did for last weekend’s contest in College Park, Md. Those expenses are balanced with missing class time and the quick turnaround between games.

Despite the fiscal losses that come with these investments in female athletics, such commitments have transformed the gender landscape.

“There was a societal stigma with women participating in athletics, which has dissipated,” Kennedy said. “But you can’t deny one of the driving forces has been complying with Title IX and the allocation of resources to the women’s side that weren’t there before.”

As the athletic department moves forward, it must continue juggling its financial decisions and Title IX compliance with always-changing NCAA regulations. A recent proposal to give scholarship student-athletes an additional $2,500 stipend would factor into that, with Kennedy saying that type of additional expense would be the equivalent to adding another non-revenue sports program.

For now, though, Kennedy and the other financial officers must remain vigilant to always examine how gender-equality in athletics can be improved.

“It’s one of the things that makes me nervous all the time, mostly because I think that what we do is part of the larger mission of the university,” Kennedy said. “Our job is to educate, and different departments use different tools for that education. And, our job is to make that educational experience as rich and fulfilling as we can possibly make it, and it’s fortunate that it helps you in terms of Title IX.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.