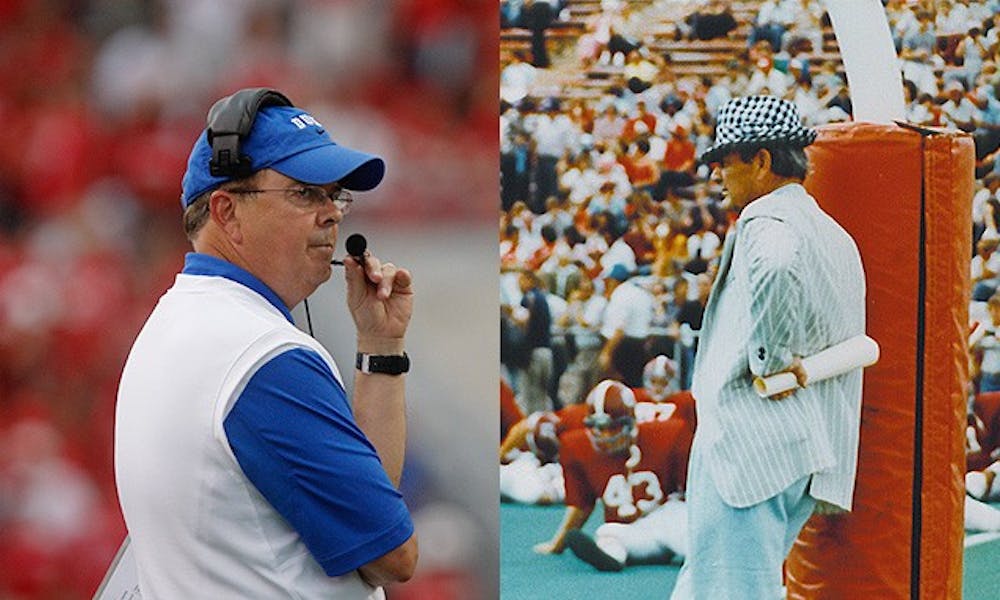

Editor’s note: This is Part 1 of a two-part series focusing on the connection between Duke and Alabama. Today, Laura Keeley writes about Cutcliffe and Wallace Wade’s history with the Crimson Tide. Tomorrow, she focuses on how the game was brought to Durham.

David Cutcliffe made an important life decision when he was five years old.

He was an Alabama football man.

“I was unusual at a very young age,” Cutcliffe said as he overlooked Wallace Wade Stadium from his wood-paneled office on the fourth floor of the Yoh Football Center. “I had no reason to be an Alabama fan. Nobody in my family had been to college. I don’t think I knew anybody that had been to college. I just, at five or six years old, was drawn to coach Bryant though his television show.”

Cutcliffe would have the chance to learn from his idol firsthand when he decided against playing college football at a smaller university and instead followed his TV hour to Tuscaloosa, an hour down the road. He enrolled at the University of Alabama in 1972 and became a student assistant to the legendary coach Paul “Bear” Bryant and his staff.

Now this week, thanks to a stroke of serendipity, he has the chance to take the field against his alma mater Saturday, like he did during his years of coaching at the University of Tennessee and Ole Miss. This game, originally proposed by Alabama five years ago, is the culmination of the promise of a home-and-home series to honor another Crimson Tide coaching legend who, after winning three national championships, shocked the football world by spurning Alabama to come to Duke—Wallace Wade, whose bronzed likeness now sits by Cutcliffe’s window at Yoh.

A Boy in Birmingham

Just as church bells have long called the faithful to worship, the Chimes at Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa called a young Cutcliffe.

“We’d go to church, and then I’d be out playing, like all kids in that era, and my mother would holler about five minutes till 4, and I’d come sprinting because I wanted to hear Denny Chimes,” Cutcliffe said. “The Chimes at Denny Stadium were right there on the quad, and that’s how the coach Bryant show started was ‘bong, bong.’ And I wanted to hear that, I didn’t want to miss it.”

Cutcliffe would sit at the edge of a bed in his family’s Birmingham, Ala. home, glued to the small black-and-white TV from 4 to 5 p.m. for The “Bear” Bryant Show. At 5, he would go back outside, never even considering watching the program that followed—The Auburn Football Review with coach Ralph “Shug” Jordan.

“And it’s so funny, it didn’t matter who Auburn had played, no disrespect to anybody, I was just a kid,” Cutcliffe said with a chuckle. “I’d go back out in the pasture that was down the road.”

With echoes of the famous Roll Tide fight song sounding in his head, Cutcliffe would make that pasture the site of his own personal Alabama football game, starring himself as the quarterback. He would drop back to throw to his receivers, a collection of tree limbs and pine cones that each had an assigned yardage and point value.

“I’d drop back, man was I accurate,” he said. “So I’d play this game that may have been played in Tuscaloosa or may have been played in Legion Field in Birmingham.”

These backyard contests, along with weekly radio Alabama game broadcasts and The “Bear” Bryant Show, sustained the young Cutcliffe’s Crimson Tide passion. Even if his family was never able to take him to see the team in person.

Cutcliffe’s devotion remained unflappable even as his older brother Paige signed with the University of Florida as a defensive lineman in 1963, when David was 12. David, who also played football, was a decent player by his own recount, but he wasn’t quite Alabama-caliber.

That wasn’t about to keep him from being a part of Alabama, his team, which had started its march to national glory 49 years before under Wallace Wade. Both, though, wouldn’t stay in Tuscaloosa long.

Undefeated, Untied, Unscored On

The year was 1930. Long before Cutcliffe was playing his simulated game with tree limbs and pine cones in his Birmingham pasture, Wallace Wade was busy lifting Alabama football onto the national stage with three Southern Conference titles and two national championships during his seven-year tenure.

At the same time, Duke President William P. Few was looking for a football coach and director of athletics to integrate college sports into the university’s culture without sacrificing its emphasis on academics. So Few wrote Wade a letter, asking for his recommendation for the job, according to an article by former University archivist William E. King.

Wade recommended two men and also mentioned that, if Duke was willing to wait one year for his contract at Alabama to expire, he would be interested in the position. Few did wait, and Wade shocked the college football world in 1931 when he accepted the job at Duke after leading Alabama to another undefeated season with a Rose Bowl victory and his third national championship.

Soon Wade was able to engineer Duke’s own rise to national prominence. In 16 years as coach, Wade had a record of 110 wins, 36 losses and 7 ties with six conference championships. His 1938 “Iron Duke” team was undefeated, untied and unscored upon until a gut-wrenching 7-3 loss in Duke’s first Rose Bowl game in which Southern California scored in the last minute of play. Wade also led Duke to the Rose Bowl in 1942, which was hosted in Durham because of the attack at Pearl Harbor, the only time the game has ever been played away from California.

In addition to sitting inside Cutcliffe’s office, Wade’s likeness also stands his own stadium in Durham and at Bryant-Denny Stadium, where both he and Cutcliffe got their start.

In the Shadow of a Legend

Cutcliffe found his path inside the program that Wallace Wade built through the role of student assistant. He started by working with assistant coach Jack Rutledge at the dorms and used the access that came with the position to study the habits of coach Bear Bryant.

He took diligent notes on Bryant’s management style and watched how he led his staff and squad. Cutcliffe still fashions his own team’s practices and weekly preparation off of lessons he learned under Bryant.

“I thought he was the master of management and the master of leadership,” Cutcliffe said of his celebrated coach. “Always having a plan, trying to leave as little to chance as you can.”

When asked to pick a favorite game from his time at Alabama, Cutcliffe struggled to pick only one. After narrowing it down to victories against Auburn and Tennessee, the school he would later make his name at, he focused in on one particular victory, a come-from-behind win at Legion Field in Birmingham during the 1973 national championship season.

“Wilbur Jackson was my favorite player. He was a running back, and he cut back across the grain on a run, and as he was running by one of the offensive linemen, you know how you slap a guy on the bottom to just say hey?” Cutcliffe said as he slapped his own knee. “He just slapped his own offensive lineman on the bottom as he went by on the way to score.”

Restoring a Program

Back in his office, Cutcliffe turned his attention to the field at Wallace Wade Stadium.

“Wallace Wade Stadium deserves this game,” he said. Then he turned to the bronzed bust behind him. “You see him, he’s got his eyes on it. Everything I can tell, Wallace Wade made the statement that he thought academic and athletic excellence should go hand-in-hand. What better to celebrate this game and his namesake stadium, so I’m excited about that, I really am.”

Cutcliffe understands that Duke does not presently share the same passion for football that exists at Alabama. Occasionally he chases people off his beloved field, wishing the community gave more respect to his place of work. He understands it will take time to build a winning football culture at Duke. He’s willing to lay the groundwork, one game at a time.

“They would put you in jail if they caught you in Bryant-Denny Stadium on the field,” he said. “Call it what you want to, it is what it is, it’s considered revered ground. There are a lot of people that I understand don’t get that. But it’s okay for us to educate in that regard.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.