From decade-old policies to the chaos of COVID-19, the University Archives and Medical Center Archives continue to tell stories of the Duke community. Yet not every story can be told there.

University Archivist Valerie Gillispie helps lead the appraisal process, the official review of records submitted to the archives.

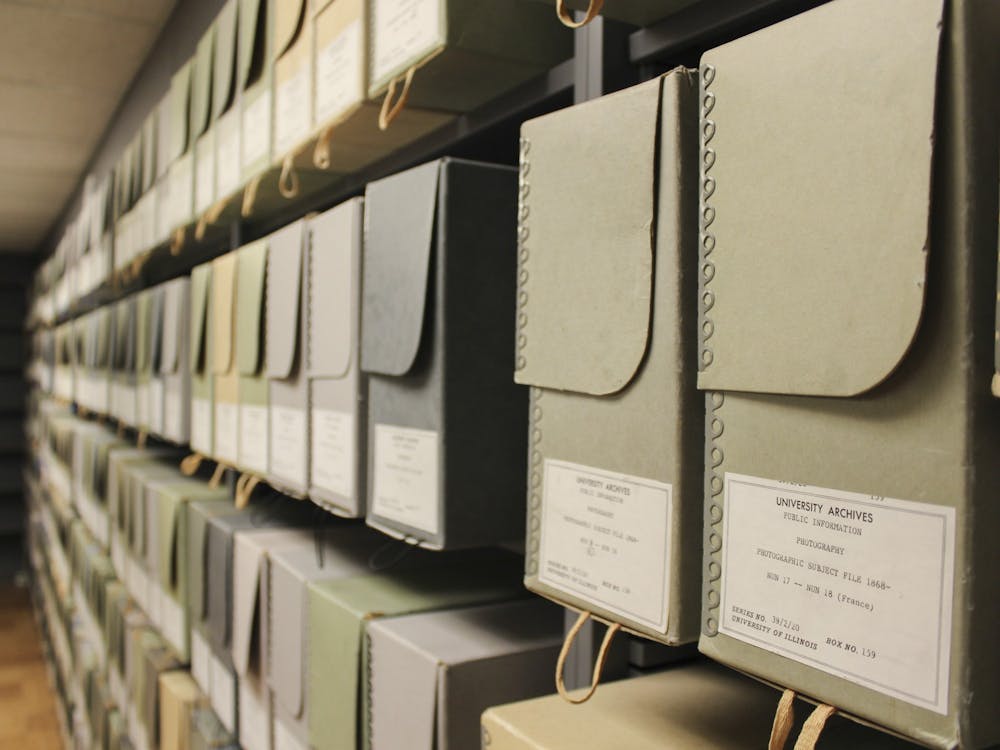

During appraisal, the archivists receive an inventory of the material: a list of file folders for physical documents and a list of shared Google Drive folders for digital documents. The staff then goes through the materials and marks which ones are worth keeping.

Gillispie said that archived materials must be of permanent historical value. Furthermore, records in the archives must also be inactive—they cannot be relevant to the day-to-day operations of the University.

Archived records such as university policies, “have value that outlasts how they were originally used,” Gillispie said.

“Even when that policy is no longer in effect, knowing about that policy and what it was, has historical value because it helps us understand both the way it was administered and what was happening on campus,” she said.

Archival material can come in many forms, including meeting minutes, annual reports and self studies.

Duke archivists work with different offices and individuals on campus to determine what is important and appropriate to archive. They also emphasize ethical considerations when making decisions, focusing more on University-wide business as opposed to an individual’s disciplinary record, for example.

Gillispie noted that because Duke is a private university and is not bound by public records laws, nothing is required to be preserved. If offices find that potential archival material could contain private information, the archives might agree to take it but restrict it for an extended period of time to protect privacy. Any material that comes out of Duke’s offices that is not publicly shared, such as private administrative correspondences, has a 25-year restriction unless that particular office gives explicit permission to publicize it sooner.

In addition to choosing what records to document, the archives also have a process for deciding how to securely dispose of materials that are no longer of value. Particularly sensitive records, such as those of human resources departments, are typically shredded.

Hillary Gatlin, records manager of the University Archives, creates record schedules that determine how long records should be kept by the owner before being transferred to the archives or disposed of. Gillispie said that they attempt to remain transparent in facilitating the destruction or maintenance of archived documents.

“We advise the office that these things should be destroyed at a certain date or that they should retain these things for so long, just so that we have kind of a trail of how we handled the material,” Gillispie explained.

The University Archives always tries to actively work with student groups and document their impact on campus, Gillispie said.

“Students are here, and then they’re gone, and the leadership of groups changes a lot,” Gillispie said. “We really try to work with them and make sure that we’re not losing that history of their group’s work.”

This emphasis has been particularly strong during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gillispie has been asking students, faculty and staff to share stories of leaving campus, their own experience with illness or any other stories they feel comfortable enough to share.

“This way, in the future, people will not only have the decisions that were made by high-level administrators, but also some sense of what it was like to be a student or staff member at Duke during this time,” Gillispie said.

While there will also be plenty of material to document from the University’s administrative response to the pandemic, most of those records won’t be stored until they are deemed inactive.

Russell Koonts, director of the Medical Center Archives, has adopted a similar approach to documenting the pandemic. He sees it as a chance to highlight the stories that are often lost in the attempt to document the administrative side of Duke.

“This gives us the chance to branch out and try to capture the entire picture of what it's like to be either a student, teacher, researcher or clinician during a pandemic,” Koonts said.

Koonts also noted that the Medical Center and University Archives are extremely similar in how they select records, both taking into consideration permanent historical value and the current relevance of the documents. While Gillispie tends to focus on records that capture the stories of the University as a whole, Koonts collects materials that relate to the Duke School of Medicine, the School of Nursing and Duke Health.

When collecting records, Koonts must be sure that the materials obey federal, state and local laws, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, which restricts the release of medical information. On the University level, he follows the same policies as Gillispie—a 25-year restriction period for administration and a 50-year period for records pertaining to the Board of Trustees.

Anyone who wants access to specific records must submit a research protocol to the Institutional Review Board and state that they will not record any personal identifiable information, according to Koonts.

If an individual wants to review records without the full IRB approval, the archivists make a copy of the record, use a black Sharpie to scratch out 18 personal identifiers—such as name, address and medical history—and then make a copy of that record as well.

Koonts said that one of his favorite parts of the archives is getting to see the role Duke has played in the history of medicine throughout the world.

“We get to see the contributions that all the people who have come through our doors—either as students, faculty, researchers or administrators—all the contributions that they have made to move medical science and healthcare delivery forward,” he said.

A story that particularly inspired Koonts was about Duke organizing a mock wedding for an OB-GYN resident and psychiatry resident after they could not hold their original ceremony. The archives have photographs and the video narrative from the event.

“It just shows that people are really resilient during this time,” Koonts said. “They're creative, and they're doing things which might not be the most optimal at times, but we're still trying to remain human and reach out and let other people know that we're there for them.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article gave an incorrect length for the restriction period for records pertaining to the Board of Trustees. It is 50 years, not 15. The Chronicle regrets the error.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Leah Boyd is a Pratt senior and a social chair of The Chronicle's 118th volume. She was previously editor-in-chief for Volume 117.