In the spring of 1973, an apathetic 17-year-old came home to an acceptance letter from Tufts University, after the other six schools on his wishlist had rejected him. Once a remote possibility, it was finally official—he would get a college experience of his own.

Forty-five years, three degrees, 11 undergraduate convocations, and several teaching and research accolades later, Steve Nowicki—the first person to hold the title of “dean and vice provost of undergraduate education” at Duke—is now preparing to vacate the role he has been in since 2007 to return to teaching and research full-time.

But this was not how Nowicki himself ever envisioned his career would unfold.

“People look at me and say, ‘Well, that’s a successful academic and scientist and with tenure,’ but it turns out my start wasn’t that auspicious,” Nowicki said, adding that 80 percent of his high school classmates did not go on to college. “I considered myself just so damn lucky to even get into college.”

But all of that changed once Nowicki entered Tufts’ campus in Medford, Massachusetts, where it was the first time he was among peers who were smart and motivated. While in college, he originally wanted to become a music major, because his high school music teacher had left a powerful impression on him. Then, he took a biology course.

“It was the most interesting thing. I kind of fell into biology just by taking a course in it in college,” he said.

After leaving Tufts and pursuing his doctorate at Cornell University, Nowicki landed at Rockefeller University for his post-doctoral fellowship, where he began his career as an assistant professor.

Nowicki attributed his collegiate success to his working-class background, explaining that he did mostly janitorial work throughout high school before returning from his first year of college to pick it up again. He added that the experience showed him what menial work really is, and that it wasn’t the kind of work he wanted to do for the rest of his life. So he had to do well in college.

“College was like going to heaven,” he said. “Smart kids, smart faculty, it was great.”

'An exception to the rule'

Despite succeeding in college and as a post-doc, Nowicki still believed his future in teaching would be at a small college.

Then Duke came calling, along with two Ivy League schools.

When Nowicki came to visit Duke, he said that he “absolutely fell in love,” and he accepted his first teaching position there in the fall of 1989.

Nowicki recalled that soon after he began his teaching career at Duke, he had been keeping in touch with two of his fellow postdocs. Those friends would only discuss the research opportunities and cutting-edge discoveries at their institutions, not the students and their achievements.

“There was a prevalent culture at large research institutions like theirs of emphasizing research over teaching,” Nowicki said. “Undergraduates simply weren’t at the center. But Duke was really an exception to the rule.”

He explained that Duke is “at an incredible sweet spot,” where research and teaching are both fundamental priorities of the University.

But Nowicki needed not wait for his former colleagues’ assessments of their own institutions to realize the significance of Duke’s dual expectations for its faculty. He explained that during that first trip to Durham, his faculty interviewers said that they were looking for somebody who’s going to “both teach well and conduct good research.”

“That was when I said, ‘If they hire me, this is where I want to be,’” Nowicki said.

Sure enough, Duke hired him, and Nowicki delivered—teaching well enough to win an undergraduate teaching award in 1993, and conducting enough research to earn tenure in the biology department.

But he may have had other motivations along the way.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“I accepted a challenge from the same two [fellow post-docs] to get both a teaching award and tenure—which they told me was impossible at an institution like Duke,” Nowicki said. “I later rubbed their faces in it through an email.”

An unlikely administrator

Several years after accepting that teaching position, Nowicki found himself at a Duke basketball watch party that would change his legacy forever.

One guest at that party—which was being hosted by several administrators whom he knew through serving on some University committees at the time—was then-Provost Peter Lange.

“Provost Lange was there, and I leaned over and asked him, ‘Is there any more I can do, in addition to being just a faculty member?’” Nowicki said.

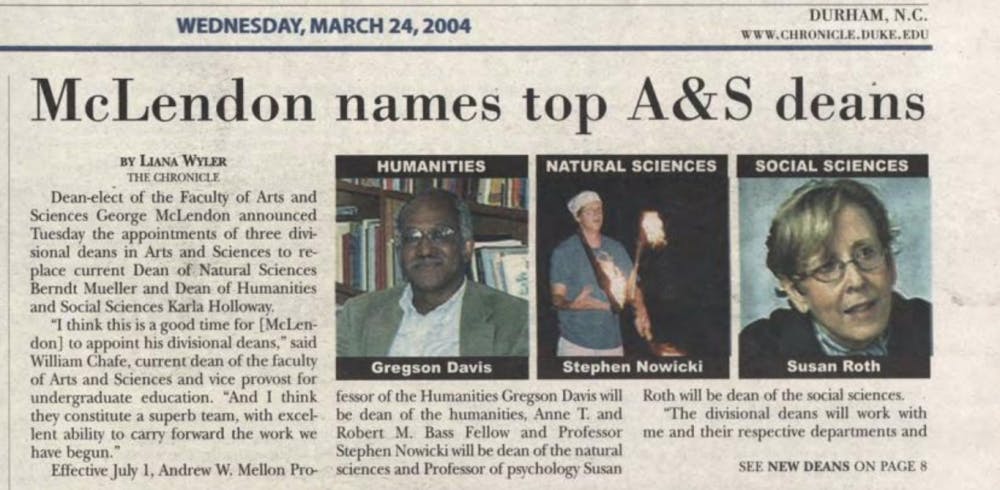

While Lange had no additional role to offer him at the time, he nonetheless remembered Nowicki’s request and, in 2004, called him to offer him the newly created position of dean of natural sciences.

Though he had never thought about being an administrator, Nowicki still gave it a shot, explaining that it was his role as dean from 2004 to 2007 that gave him his first glimpse into the actual workings of the University.

“Honestly, at first, I thought being an administrator was useless—just filling out forms,” he said with a chuckle. “I think differently now, obviously.”

Nowicki's work in his role as a dean was enough to garner the attention of Lange and then-President Richard Brodhead when the administration prepared a search for the school’s first dean and vice provost of undergraduate education.

Nowicki explained that he believes it was his reputation for having a good rapport with the student body that caught the attention of his fellow administrators and ultimately made him their choice for the position in 2007.

Nowicki was reappointed a second five-year term as the dean and vice provost of undergraduate education in 2012, explaining that there was “too much left to do” to call it quits after just one term. As his second term drew to a close, he resolved that he would step down, upon hearing the news that Brodhead would be retiring as president that same year. He later informed Provost Sally Kornbluth that he’d be serving one final year so that newly elected President Vincent Price would have some continuity.

Although Nowicki was happy to serve both terms, he believes change is beneficial for institutions in the long run.

“[Change] allows new ideas to surface, keep things fresh,” he said. “Plus it’s good for the individual, and I think I’ve done enough.”

Paying it forward

Nowicki praised the student body for their support in his new role—particularly early on—explaining that his job description often involved simply making the description relevant.

“I remember [President Brodhead] saying, ‘Okay, now figure out what this job does,’” Nowicki said. “The students were great, though—they finally had a point of contact in administration that they really just didn’t have before.”

Nowicki recounted one particular example when this new point of contact came in handy—when one student named Paul Slattery, Trinity '08, came to him with an idea Slattery called “FLUNCH.”

“He came and talked to me about it, and FLUNCH took off and became what it is today,” Nowicki said, adding that he doesn’t believe the program would have taken off to the extent that it did if Slattery had gone directly to Student Affairs or Duke Dining.

While Nowicki was helping students realize their ideas in his new role, these same students were imparting to him what he called the greatest lesson he learned on the job.

“One thing that is an important lesson is how hard it is to really listen deeply—to not just hear things. That’s true for working with anybody, and it’s especially true for students because every year a quarter of the students are new,” Nowicki said.

He explained that he would often hear the same things—both good and bad—from every incoming class. But that didn’t make it less important for him to listen to every word they said.

“If nine of the 10 things that students have said you’ve heard before—if you just sit there and nod politely and mumble ‘mhm, mhm’ while they’re speaking—then you’re going to miss the one thing you haven’t heard before,” Nowicki said. “And as many times as I’ve already heard these things, it is all new for the students who come to see me.”

So it’s no surprise that some of Nowicki’s fondest memories in his position revolve around the student body.

For example, a few years ago Alison Rabil, director of financial aid, met with Nowicki to discuss a issues that first-generation, low-income students at Duke were consistently and uniquely facing. Out of their discussions came a few pilot programs before Nowicki and Rabil went and pitched the foundation of what would become the David M. Rubenstein Scholars program to the president and provost.

“They liked it so much that they wanted us to have it ready for the following summer,” Nowicki said. “That is one of the things I’m so happy we have achieved.”

Another highlight on the job for Nowicki was seeing his students’ hard work pay off both in and out of the classroom. He considers it a triumph whenever a student he’s teaching shows considerable improvement over the semester.

“When a student gets a C on the first exam and then an A on the next one, that’s the kind of stuff that gets me out of bed every day,” he said.

Ironically, it was Nowicki’s passion for “paying it forward” to his students through teaching that inspired him to retire from a position created to serve the students.

He explained that if not for the encouragement of his English, music and drama teachers, he might never have gone to college at all.

“In their own ways, they saw something in me and encouraged me. And to the extent that anything came out of me in high school, I gave them credit for it,” Nowicki said. “I just felt like I was being given a gift in college by these faculty members who really cared about students in general and who really cared about me. And I just feel like I owe it to the world and to them.”

For all that teachers can do to leave a lasting impression on their students, teaching is still a two-way profession, he said, explaining that the way his students learn from him is very different from the way he learns from his students. To illustrate his point, Nowicki recalled an anecdote from his Principles of Neuroscience course back during the fall semester of 1993.

Despite having taught this course three times already, Nowicki could not iron out an abrupt transition that bridged two major concepts of the course.

“For whatever reason, it just did not come naturally to me,” he said. “But I knew that if I could explain that bridge less abruptly to students, I could teach the course much better.”

So he vowed to solve it, spending a month over the summer preparing an entirely new lecture presentation dedicated to smoothing the transition. When the day came for Nowicki to deliver that lecture, he finished feeling like he had nailed it, until one student came up to him afterward and asked him a question.

“Steve, what was that lecture about?” Nowicki said the student asked.

“They’ll come right up to you and say, ‘This makes no sense.’ And to have them here on this campus—these bright young members of the University community who just think differently than the rest of us do—that’s really just a wonderful thing,” Nowicki said.

Highs and lows

In keeping with his passion for Duke students, Nowicki said that the beginning of the academic year has always been his favorite time of year, citing the “Let’s get something done!” mentality and the opportunity to welcome returning students back to Duke.

But, judging by the time he annually devoted to preparing his 11 speeches at Convocation, he may always have a sweet spot in his heart for welcoming the newest batch of Blue Devils to Durham.

“Let’s just say the month of July would be more or less about writing that speech,” he joked.

Another of Nowicki’s favorite activities as dean of undergraduate education was being a member of the pep band, which he described as the most fun part of his job that “didn’t necessarily come with his job.” He added that he originally got into the pep band when he first became an administrator, which means that as he retires from administrating, he will also be retiring from playing the trombone in Cameron Indoor Stadium.

“It was a great ride, but I don’t think a random faculty member should be a part of the pep band,” he said.

But it wasn’t all fun and games for Nowicki along the way. One of the hardest parts of the job, he said, was simply learning how to become a better manager. He pointed to signing time cards, performing annual reviews and letting his employees go as some of his most difficult responsibilities.

There is one particular memory that Nowicki will never forget—the first time a student died on his watch. He mentioned that he still remembers going with Brodhead to meet the student’s parents at the hospital—the parents of a student he had known and taught in his own classroom.

“Boy, there’s nothing that could have prepared me for that," he said. "And it’s nothing I’ll ever be able to forget.”

“My door Is always open”

When asked what he will miss most about his current position in the administration, Nowicki didn’t think twice before rattling off his response.

“The opportunity to meet students across all kinds of disciplines,” he said. “Duke students are, on the whole, super interesting. And I’ve just met a ton of really interesting people who are econ majors, classical studies majors, sociology majors, etc.”

He added that one of the things he has always appreciated the most about Duke students is just how much they love Duke, and how mutually supportive they are of each other—as this is not always the culture awaiting students at other schools.

As supportive a place as Duke can be, Nowicki mentioned that he hopes he will continue to see Duke become even more inclusive of the diversity of backgrounds and perspectives it is admitting to campus.

Rather than creating a culture where incoming students feel the need to conform into a “Duke student,” it is through encouraging them to continue being whoever they are that will make for the best learning environment possible, he explained.

“I would love to have students say: ‘I own this place. It’s mine. I may not like one part of it, but I’m going to try and do something about that part of it for both the benefit of myself and my fellow classmates and the students who will come after us,’” he said.

And if Nowicki’s thoughts on his successor are any indication, the Duke undergraduate experience will only continue to get better moving forward.

Nowicki said that he was delighted when he heard the news that Gary Bennett, founding director of Duke’s undergraduate major in global health, had been selected as the new dean and vice provost of undergraduate education. Nowicki joked that he doesn’t believe it will take long before all of his colleagues forget about “that guy Steve they used to work with.”

Nowicki—who will be moving from the Allen Building to his new office in Biological Sciences 214 at the conclusion of his service to the administration—added that he still plans to remain a resource for Bennett whenever he comes to him with questions or concerns.

As for the Duke student body, Nowicki had just eight words to offer.

“Stop by anytime," he said. "My door is always open.”