A North Carolina woman pleaded guilty after she was caught fraudulently obtaining more than 8,000 hydrocodone opioid pills—all using a Duke neurosurgeon's name and DEA number.

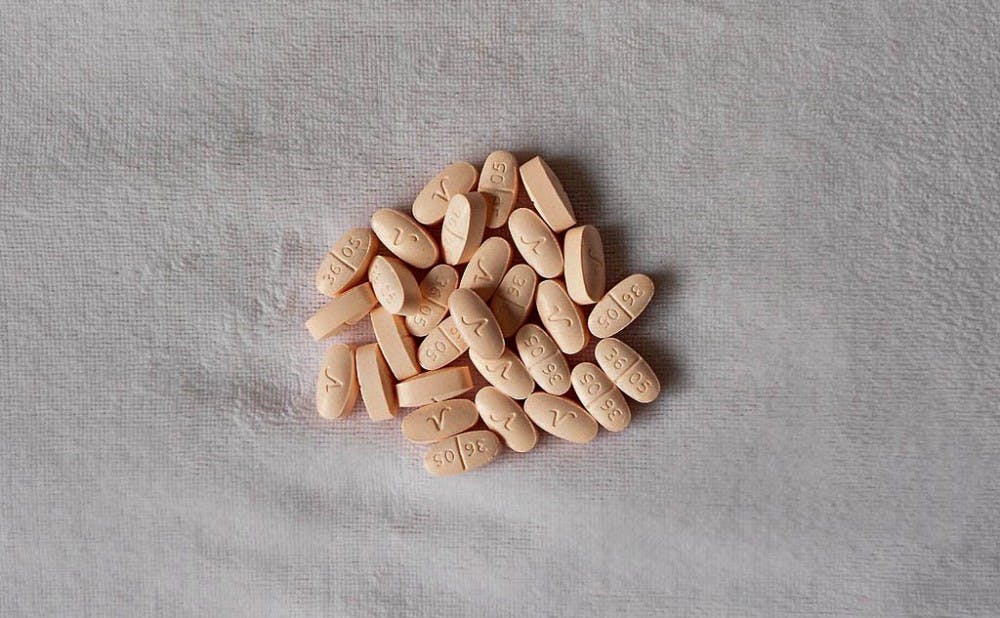

Heather Smith Elliott, from Burlington, N.C., pleaded guilty Oct. 4 in the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina to two counts of using forged and fraudulent prescriptions to obtain the hydrocodone pills, one count of wire fraud and one count of aggravated identity theft. She forged 132 prescriptions for herself, family members and friends for hydrocodone, a pain-relieving opioid and Schedule II controlled substance.

The Duke neurosurgeon, whose name was not released in the Department of Justice press release, did not have Elliott—or any individuals who illegally received the pills—as patients. The neurosurgeon similarly did not provide any legitimate prescriptions to any of the associates.

As unusual as this case seems, Professor of Medicine Lawrence Greenblatt argued that it is just that—unusual.

“Fraudulent prescriptions are a tiny percentage of the total of prescription pills that are being abused out there,” said Greenblatt, also co-leader of the Duke Opioid Safety Task Force. “It's really not a significant problem.”

However, Greenblatt added that he believed that physicians could learn several lessons from this case. He said doctors must be careful with their paper prescription pads, which are sent to pharmacies when a drug is prescribed. Those pads, however, may become a relic of the past with universal electronic prescribing, he explained.

Udobi Campbell, associate chief pharmacy officer of Duke Ambulatory Pharmacy Services, stressed the importance of electronic prescribing.

“We take our performance for e-prescribing very seriously at Duke," she wrote in an email. "In fact, it is monitored as one of our medication safety metrics that is reported out to hospital leadership.”

Nevertheless, not all controlled substances are prescribed electronically yet, Campbell noted, because broad system changes are still needed.

Another point of emphasis for Greenblatt was the statewide Controlled Substance Reporting System (CSRS)—a database where physicians and pharmacists can see a patient’s opioid prescription record and where doctors can check their own prescriptions.

“[The Duke neurosurgeon] could have caught her a long time ago had he been periodically looking at his [CSRS] report,” Greenblatt said. “Most prescribers don't routinely use the Controlled Substance Reporting System even though the majority have registered at least. In day-to-day practice, people say, ‘Oh, I'm too busy to look that stuff up, I just do what I think is best.’”

Since neurosurgeons are extremely busy, Greenblatt believed simple analytics should be added to the system that could catch anything egregious—for instance, 132 false hydrocodone prescriptions.

Elliott’s case, though rare, provides insights into pharmaceutical structures in place that have propped up the opioid crisis. She received over 8,000 pills with roughly 132 prescriptions—an average of almost 61 pills per prescription. With so many opioids being prescribed to patients, it is no surprise that 70 percent of opioid abusers receive their pills from family or friends who have more than they need, according to a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration survey.

Of the 8,000 pills Elliott received, a portion of them went to her ex-husband, an ex-boyfriend, a former employee, her son and a neighbor.

In response to the opioid crisis, doctors and lawmakers are working to reform the prescription process.

Campbell referenced Duke’s multi-prong approach, which includes “educating about proper use and prescribing of controlled substance medications,” as well as “strategically install[ing] receptacles at two of the Duke retail pharmacies for disposal of medications no longer needed by consumers.”

State lawmakers have also taken initiative on the issue. Gov. Roy Cooper signed the Strengthening Opioid Misuse Prevention Act June 29, which will go into effect Jan. 1, 2018. The law limits prescriptions to a five-day supply for acute pain and seven-day supply following surgery. Additionally, it requires doctors to enter prescriptions into the CSRS and consult the a patient’s record before writing a prescription.

As for Elliott, her sentencing is scheduled for Jan. 18, 2018. Obtaining a controlled substance with a fraudulent prescription is punishable by up to four years in federal prison, while wire fraud and aggravated identity theft are punishable by up to 20 years and two years, respectively. She also faces a fine of up to $250,000.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Jake Satisky was the Editor-in-Chief for Volume 115 of The Chronicle.