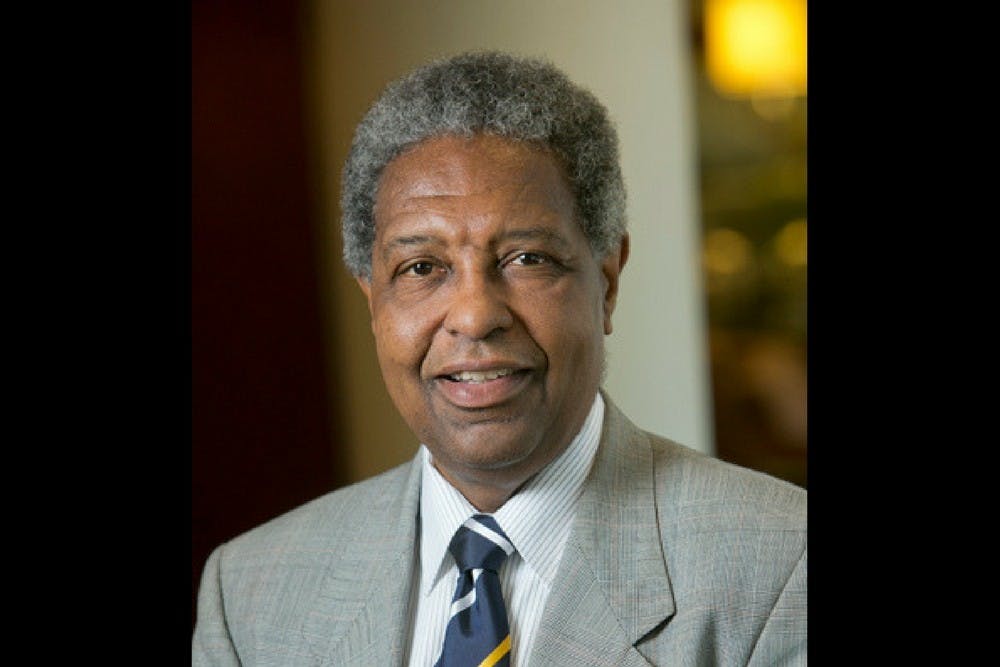

William Darity Jr., Samuel Dubois Cook professor of public policy, recently helped edit and write “For-Profit Universities: The Shifting Landscape of Marketized Higher Education." The Chronicle spoke with Darity about the book and the role of race, class and other factors in the rise of for-profit universities. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Chronicle: Why did you decide to help write this book?

William Darity: It’s probably been about seven years that I’ve had some focus on for-profit universities. This was a book that was edited in collaboration with Tressie McMillan Cottom who is at Virginia Commonwealth University. She’s a sociologist, and her area of specialization is for-profit universities. In the process of having conversations with her, I became aware of the significance of the growth of for-profit universities and their importance particularly for segments of the population who are most likely to be excluded from educational opportunities. So eventually we submitted a proposal to the American Educational Research Association to get funds to put together a conference, because both of us had the impression that there really wasn’t adequate scientific research on for-profit universities. We tried to identify the folks who were doing that or were more likely to be doing that to bring them together for convening. And that convening ultimately yielded the papers that were in the edited volume that we now have just put out.

TC: This book ties race, class and gender into its discussion, which is unique because previous research on for-profit universities hasn’t really done that. How do for-profit universities perpetuate inequality and prey on certain groups of people like African Americans and women?

WD: What happens is that the for-profit universities prey upon those members of our national community who have the least resources but the greatest determination to get additional education. In a way, they’re preying upon people who are highly-motivated to pursue additional schooling, but who typically don’t have a great deal of money. Those folks usually have to rely on public-sector money to support their education. So the irony is, in effect, that the for-profit institutions are relying very heavily on public monies for their sustenance and profits. They’re kind of pass-through government contractors.

TC: What role has changing labor markets and deteriorating social safety nets played in the growth of for-profit universities?

WD: I’m not sure if it’s changes in the labor markets, per se. But definitely the for-profits are geared toward emphasizing the vocational or instrumental dimensions of education. Folks who attend for-profit universities are frequently doing so because of expectations that the degree that they’ll get from that institution will put them in a position to have a quality job, better earnings and the like, so it’s very vocationally oriented. It’s not geared toward the principles that we would typically associate with a liberal arts education. It’s far more instrumental. That’s something that is disturbing about it.

TC: What is the solution or alternative to for-profit universities?

WD: You really have to alter the structure of opportunity for groups that have largely been excluded from the fruits of American society. Communities of people who are most likely to turn to for-profit universities are those folks who are mostly likely to be unable to afford or to be accepted at more selective, traditional colleges and universities. They also are folks who probably have had more limited opportunities to get a high-quality high school education. We have to address those kinds of circumstances to try to change the entire nexus of options for folks who are in those positions. That would involve ensuring that people have quality employment regardless of which academic institution they went to—ensuring that all Americans actually had a high-quality high school education that prepared them for attending colleges that offer a liberal arts curriculum, so that everybody would receive a strong critical thinking education. It’s more of a question of transforming the conditions in the wider society than necessarily regulating the for-profit universities. No matter how much you regulate them, they will resurface in some form or fashion as long as there is a demand for their services. So we need to create conditions where demand for their services is greatly reduced.

TC: Do you see any real role for them in the educational landscape?

WD: That’s a tough one. I certainly think that there’s a role for institutions that provide people, if they so desire, with a specific set of skills that gear them toward very specific occupations. But that can actually be done quite effectively through the community college structure if we can improve our community colleges. So we wouldn’t necessarily have to turn to a private sector that is a for-profit private sector for the purpose of providing people with those kinds of skills. Depending on how we view the community college structure, that would determine whether or not the for-profit universities are performing a largely-redundant function.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.