This is the first story in a multi-part series on the student conduct process. The Chronicle has changed the name of the student referred to as Jane Doe due to the sensitive nature of the story. Doe’s account is based on interviews with her as well as documents she provided to The Chronicle from the student conduct process.

Jane Doe received an email last April that no student wants to open. The message, from a dean at the Office of Student Conduct, explained that she was under investigation for allegedly cheating on a series of public policy quizzes. After five months, Doe was found not responsible for cheating. But Doe doesn’t think what happened during those five months was fair.

“The burden of proving that I was innocent was clearly on me,” she said.

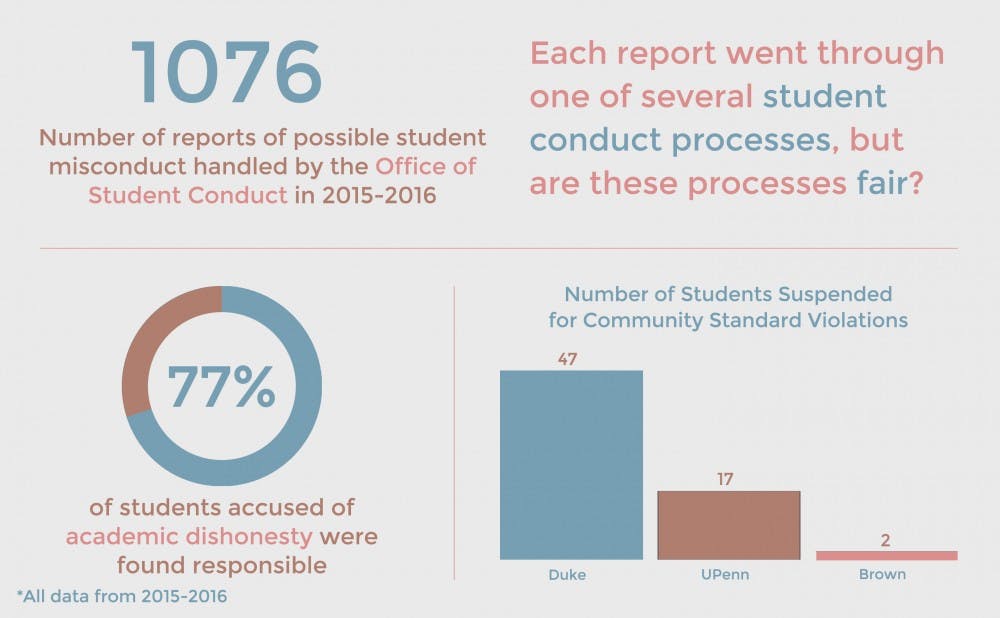

In the 2015-16 school year, the Office of Student Conduct handled 1,076 reports of possible student misconduct, and 47 students were suspended for community standard violations, a much larger number than that of Duke’s peer institutions.

Each of these reports wound its way through one of several student conduct processes, from faculty-student resolutions to conduct boards.

Students and legal experts interviewed by The Chronicle have raised further questions about the fairness and robustness of how conduct investigations are handled.

‘A lot of evidence’

Doe’s case was one of 170 brought against students in 2015-16 for allegedly cheating in class. Almost 77 percent of students accused of all types of academic dishonesty—including cheating, plagiarism and lying—in 2015-16 were found responsible in the student conduct process. OSC sees more cases involving academic dishonesty than any other issue besides alcohol violations.

In order to be found responsible for academic dishonesty, there must be clear and convincing evidence that a student has cheated, lied or plagiarized, according to the Duke Community Standard. But Doe got the impression early on in the process that it would be hard to convince OSC that she hadn’t cheated.

Doe’s professor, Evan Charney, associate professor of the practice in the Sanford School of Public Policy, accused her of consulting unpermitted help while taking weekly in-class quizzes on her laptop using a special testing software called Electronic Blue Book. Charney based this accusation on logs from the testing software, which appeared to show that Doe had taken an unusually long time when completing the quizzes or had taken the quizzes outside of class time.

But EBB was supposed to lock down Doe’s laptop when she was taking the quizzes and not allow her to run any other programs or visit any websites. And yet, Doe was able to give OSC records of her web browser history showing that she had been doing other things—from working on other classwork to browsing Amazon—at the times when the EBB records supposedly showed that she was taking the quizzes. Doe also obtained statements from friends who were at group meetings or doing work with Doe when the EBB records indicated she was taking quizzes.

“I immediately went back and went through every single quiz date and looked for evidence to support my argument, because I knew that no one was going to believe me if I just said, ‘I didn’t do it,’” Doe said. “And thankfully I was able to find a lot of evidence.”

Doe provided more than 10 pages of documentation to OSC supporting her claims and arguing that she could not have been taking the quizzes at the times indicated in the EBB logs. She insisted that there must have been an issue with EBB. She provided evidence from a forensics expert, an Apple support technician and the developer of EBB suggesting that adware on her computer could have caused an issue with EBB.

OSC forwarded Doe’s document to Charney. In response, he insisted that the evidence Doe had assembled was all a lie.

“You are curious to hear my response? I believe that this entire document is an elaborate and well thought out deception,” Charney wrote in an email to Associate Dean of Students Leslie Grinage, who was handling Doe’s case. “No such ‘glitch’ regarding time stamps has ever occurred during [the Sanford information technology manager’s] 10 years of using EBB. We checked the timestamps of all of the other students who took quizzes at the same time as [Doe] and they all show expected start and stop times.”

Charney did not respond for request to comment Tuesday evening.

Doe also claimed that she repeatedly offered to let OSC have her laptop for investigation, but they declined the offer. OSC did, however, take logs from EBB that were stored on Doe’s computer and send those logs to the developer of EBB for analysis.

James Coleman, John S. Bradway professor of the practice of law and co-director of the Wrongful Convictions Clinic at Duke, noted that in Doe’s case, OSC could have done a forensic investigation of Doe’s laptop at the outset, rather than leave it to Doe to find a forensics expert.

“A thorough system would have done the forensic investigation first,” he said. “If there’s a possibility that what’s going on here is that the software is not working, then that ought to be eliminated as an investigation before you bring charges against somebody.”

Doe added that she met with Grinage to discuss her case, and during the meeting, Grinage asked her questions about seemingly unrelated topics, such as whether she was actually sick during classes that she had used short term illness forms to get excused.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Robert Ekstrand, a Durham lawyer who has worked on hundreds of disciplinary cases involving students at Duke and other institutions, was involved in the lacrosse case and helped Doe with her case, said that he has seen many cases in which either OSC or an Undergraduate Conduct Board has dismissed evidence that appears to exonerate a student as irrelevant or fabricated.

“I can’t recall a case where compelling evidence of innocence is presented to OSC administrators and they said, ‘Oh gosh, never mind,’” Ekstrand said. “I hope it happens, but you would think that I would have seen one or two of those.”

The hearing

Several weeks after classes ended, Doe’s evidence was indeed dismissed, and her case was sent to an Undergraduate Conduct Board, which decides serious cases of alleged Community Standard violations. Because Doe had assembled so much evidence that she wanted to explain in person, she decided to fly back to Duke for a July hearing and face the board rather than attend via a video call.

“I thought it was really important that I be there during the hearing,” Doe said. “Part of the story is that [the process] incurred a lot of costs for my family—flying up, rental car, hotel.”

However, Doe told The Chronicle that on the day of the hearing, OSC notified her of potential problems with the panel. First, OSC told Doe that some of the documentation she had provided supporting her claims had not been given to panel members until the day of the hearing, and as a result, the panel may not have had time to review the documentation. In addition, the panel did not have the intended number of students because it was occurring in the summer, and one of the panelists had a conflict of interest with another, Doe said.

As a result of these issues, Doe said that OSC gave her the option to postpone the hearing. But OSC required that if she went ahead with the hearing, she would have to waive her right to appeal based on any of those particular issues. Because Doe had flown to Duke for the hearing, she could not easily postpone it, and therefore waived her rights, she explained.

“For me, [postponing] wasn’t a real option because I had just spent so much money flying to Durham, and I was already there at that point, so I couldn’t just say, ‘Let’s cancel the hearing,’” Doe said. “So I just ended up having to waive my rights.”

Ekstrand said that he has seen similar situations in a number of other cases.

“You see it a lot. It raises issues and questions. Often students are asked to waive certain rights in the 11th hour. They get to their hearing, they’re completely exhausted, it’s been an ordeal and they’re ready to present their entire case all by themselves,” he explained. “And then they’re told, ‘Oh, we have this new panelist and you might know him or her but you can waive your right to object or you could object and we will reschedule the hearing.’ And at that point all the student wants to do is just sign and say, ‘Let’s just get this over with.’”

The hearing panel found Doe responsible for cheating by a 3-2 vote. Doe said that the panel heard from the developer of EBB, Chris Bombardo, who told the panel that adware—software that downloads or displays advertising material—had previously caused glitches with EBB, but the panel did not find that convincing.

The panel then voted to give Doe a two-semester suspension, among other sanctions. It had to unanimously approve the suspension, and it did so even though it only found Doe responsible by a bare majority.

“It’s not logical for two people on that panel who didn’t believe that I had done anything wrong to then sanction me for two semesters of suspension. Logically that doesn’t make sense,” Doe said. “But once again, those aren’t things you can appeal upon because they are things that are technically justified in the Community Standard.”

When asked about why panels can vote with a bare majority to find a student responsible but then can suspend them, Stephen Bryan, associate dean of students and director of the Office of Student Conduct, explained that panelists are under no obligation to vote against a suspension even if they voted that a student was not responsible.

“There is no expectation that if a hearing panelist votes to find a student ‘not responsible,’ that that hearing panelist is then expected to vote on the sanctions if the student is found responsible,” Bryan wrote in an email. “In other words, we do not require hearing panelists to vote for a sanction if in fact they voted ‘not responsible’ for the violation. In reality, this is typically not a germane issue, as most often hearing panels are in consensus about their decision.”

Bryan did not explain, however, why suspending a student after a bare majority finding of responsibility would not violate the spirit of the rule stated in the community standard that suspensions must be unanimously approved.

In 2015-16, OSC reported that 47 students were suspended for community standard violations, the large majority for one or two semesters. Peer institutions which release student conduct statistics have had far fewer suspensions. In 2015-16, the University of Pennsylvania suspended 17 students, and Brown University suspended two students. In 2014-15, Harvard suspended 25 undergraduates, Northwestern University suspended 7 students and the University of Chicago suspended 12 undergraduates.

Ekstrand said after looking at reports from a number of other institutions, he arrived at the conclusion that Duke suspends far more students than its peers.

“I looked around and saw that peer institutions are suspending 1/20th of the number of kids,” he said.

He also questioned the value of suspending a student in cases of first-time academic dishonesty offenses, arguing that the University was missing a significant teachable moment by simply sending a student home.

"How is Duke discharging its obligation to educate by suspending that student, sending him home with his tail between his legs and stamping ‘academic dishonesty’ on his transcript? I have not received a satisfying answer,” Ekstrand said. “It seems to me that, by simply suspending a student in that circumstance, Duke is missing an opportunity to have a meaningful impact on the student and to teach at the highest level."

The appeal

After the suspension, Doe hired a lawyer and engaged another forensics expert to help prepare an appeal. She appealed on the grounds that the panel’s finding had “no plausible basis in fact” because of the technical evidence she had submitted, as well as on the strength of new evidence from the second forensics expert pinpointing how EBB had malfunctioned on her laptop.

Doe’s appeal was accepted, and her case was sent to a new hearing panel, even though the community standard says that successful appeals should be sent to the original hearing panel, a fact which was significant in the Ciaran McKenna case. McKenna, who was suspended for six semesters from the University for sexual assault, is currently arguing in court that an appeals board does not have the option to send a case to a new panel and instead must either resolve the case or send it back to the original panel. McKenna won an injunction against the University allowing him to continue taking classes while his case proceeds.

Since Doe’s appeal, the Community Standard has been updated to remove the “no plausible basis in fact” argument as a grounds for appeal.

This grounds for appeal was also previously weakened—students used to be able to appeal if “the finding of responsibility was inconsistent with the weight of the information.”

Larry Moneta, vice president for student affairs, said that this was changed and then removed because it was creating confusion on the function of appeals in the student conduct process.

“It was not being interpreted correctly in most cases and often created confusion about what that aspect was intended to cover,” Moneta wrote in an email. “Appeals are intended to assure compliance with proper procedures and those are the current grounds for appeal.”

Ekstrand said that he has observed a pattern in which Duke has changed the Community Standard after a number of students successfully appealed the findings of a conduct board on the same basis.

“I can almost predict it—they’re going to change the rules,” Ekstrand said. “That suggests that whoever is changing the rules is responding to what’s working to protect the students—by taking it away."

The recent changes to students’ ability to appeal due to a lack of evidence presented to the panel illustrate this point, he noted.

"Most recently, after we won a number of appeals by showing that the evidence did not support the panel's finding of responsibility, the rules were changed to restrict that basis for appeal,” Ekstrand said. “And when we kept winning appeals on that basis, the rules were changed again, this time to remove the sufficiency of the evidence as a basis for appeal altogether."

Doe also ran into problems during her second hearing.

She said that OSC would not let her listen to an audio recording they had taken of the first hearing when she was preparing for the second hearing.

“The problem that I was having is that they were saying, ‘This was a new hearing, so you can’t mention any reference to the previous hearing. And you can’t mention any previous testimony,’” Doe said.

But a critical part of Doe’s case was the evidence she had assembled and presented in the first hearing.

She said she told OSC that she would include information from the previous hearing in her report for the second panel, whether OSC wanted her to or not.

“[OSC] was like, ‘Look, if you don’t take all this information out, all the mentions of the previous testimony and the previous hearing, we will redact it for you,’” Doe said. “And then actually what I ended up doing is I redacted it myself, and everywhere I took out information I put, ‘Corroborating evidence has been redacted at the request of the Office of Student Conduct.’ Because it was. That’s the factual statement, and it also bears no mention of the previous hearing. And obviously they didn’t like that very much, so finally they just accepted the original statement [without redaction].”

Doe noted she is glad that she was eventually allowed to include evidence from the previous hearing in the second hearing. The developer of EBB once again talked to the panel, but this time seemed to indicate that EBB could not malfunction. Doe was able to use the information she had presented from the previous hearing to show that he had contradicted himself.

Doe added that the panel almost did not call a forensics expert who had evidence that was crucial to her case.

“You can present witnesses on the list, but the panel reserves the right as to whether or not they’re going to call them,” she said. “I hired a second forensic witness, and they almost didn’t call him. This is the guy who identified a specific code in the software that’s making it glitch—you have to call him.”

After the hearing, the panel found Doe not responsible for cheating by a 4-1 vote. Before Doe received her decision, the chair of the second panel had some advice for her.

“He started off by saying that, ‘There are a lot of people on this panel who very much think you are guilty. I hope you come out of this process with an appreciation for our student conduct process,’” Doe said.

Doe says that she did not appreciate the advice.

“They did everything they could to make me feel guilty despite the fact that they found me not responsible,” she said.

If you have had experiences with the Office of Student Conduct that you would like to share with The Chronicle in a confidential manner, please contact Claire Ballentine at claire.ballentine@duke.edu or Neelesh Moorthy at neelesh.moorthy@duke.edu.

Correction: The graphic on this article has been updated to note that Brown University had two suspensions in the 2015-16 year, not Harvard. The Chronicle regrets the error.