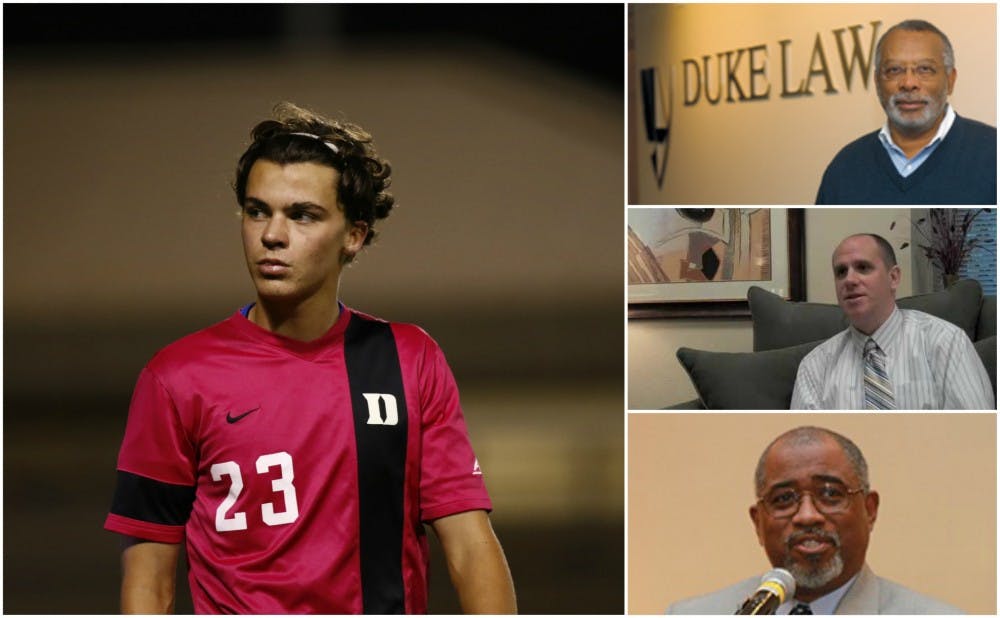

As litigation continues about whether Duke improperly suspended men's soccer player Ciaran McKenna for rape, a superior court judge has allowed him to stay on campus as a student.

After being suspended, McKenna sued Duke and Dean of Student Conduct Stephen Bryan on the grounds that the University violated its own policies during the disciplinary process. Hudson granted a preliminary injunction Wednesday that will allow McKenna—who was previously suspended six semesters—to remain at Duke for the time being.

The injunction does not constitute a final determination that Duke erred, just that McKenna should not be suspended while either the court or a jury further decides the issue.

After convincing the judge to make the complaint available publically, The Chronicle was able to review McKenna’s filing, which included exhibits, two hearing reports and supporting documents. The Chronicle has constructed a timeline and explanation of events based on the documents filed in court by McKenna’s lawyers and by the University.

Those involved in the lawsuit either could not be reached for comment in time for publication or declined to comment.

The night of the alleged assault

The alleged sexual assault occurred early in the morning Nov. 14, 2015, after the alleged victim and McKenna—both first-years at the time—met at Shooters II Saloon. According to his filing, McKenna, who was 17 at the time, and the female student agreed they made out while dancing before returning to her dorm room.

The female student invited McKenna back to her room with the intent to only continue making out, according to McKenna’s appeal after the first hearing, but McKenna alleges that she did not object when she saw him pick up a condom from his room before going to hers. McKenna says in his statement of facts in the first panel that they engaged in consensual sexual acts before and after intercourse in her room, and that during sex, his condom kept falling off. According to his statement of facts, the female student told McKenna that he did not have to wear one.

However, according to the second panel’s report, the female student claimed she did not want to lose her virginity when McKenna reached to grab the condom, pulled away from him before sex and said no during intercourse. When McKenna spoke to the second panel, he said the alleged victim actively consented through her movements.

The alleged victim is not a party to the lawsuit. She declined to comment to The Chronicle.

The original hearing panel

The first of two hearing panels in the case convened July 7, 2016. The three-person panel required a unanimous verdict to sanction McKenna and considered two questions—whether the female student verbally denied consent and whether her nonverbal actions constituted affirmative consent.

The original panel was not unanimously convinced that she verbally said no, with one member questioning the female student’s account. However, the panel did unanimously conclude that “his version of the events that led up to sexual intercourse fails to show that the complainant clearly and affirmatively consented to having sexual intercourse.”

As a result, the panel unanimously agreed on a six-semester suspension. In the report, the panel notes that it considered expulsion but lowered the sentence after considering mitigating factors, such as McKenna’s age when the incident occurred, his clean record and statements McKenna made to suggest he would alter his future behavior.

The chair of the panel was Li-Chen Chin, assistant vice president for intercultural programs. Jerrica Washington, former student involvement program coordinator, and a current senior student were the other members. Leslie Grinage, assistant dean of students, is listed as a facilitator. Tim Young, assistant director of development and alumni relations in the Sanford School of Public Policy, was McKenna’s advisor and Adam Hollowell, visiting professor in the religion department and Sanford, was the alleged victim’s advisor.

According to Duke’s student misconduct policy, the panels typically consist of two faculty and staff members in addition to a student.

Duke’s requirement of a unanimous verdict from a three-member board is different from that of its peers. According to The New York Times, Duke and Stanford University are the only schools in the U.S. News & World Report’s list of the country’s top 20 colleges that have such a requirement. Stanford also uses a three-member panel, but Harvard University and Columbia University instead have the investigating Title IX officer or investigative team issue a final judgment, subject to an appeals process.

A gray area

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

McKenna appealed the original panel’s findings July 29, 2016 because he did not think the panel correctly applied the “reasonable person standard” to the question of whether the female student’s actions constituted affirmative consent. By that standard, outlined in Duke’s sexual misconduct policy, McKenna needed to show that a “reasonable person” would have believed the female student was consenting based on her actions.

“Conduct will be considered ‘without consent’ if no clear consent, verbal or nonverbal, is given,” according to the sexual misconduct policy. “The perspective of a reasonable person will be the basis for determining whether a respondent knew, or reasonably should have known, whether consent was given.”

The report from the first panel, included as an exhibit to the lawsuit, does not mention the phrase “reasonable person” anywhere.

Another main pillar of McKenna’s original appeal was that the first panel did not fully consider evidence that he argues could have affected the alleged victim’s credibility. In particular, the female student argued to the original panel that one of the reasons she said she did not want to have sex was that she was a virgin. However, McKenna claimed that one of his teammates had a previous sexual relationship with the alleged victim.

The panel tried to get in touch with that teammate during the hearing. Although the panel’s facilitator called the teammate three times at a time in which he said he would be available, there was no answer, per the original hearing report. According to the lawsuit filing, the panel attempted to contact the teammate using an unknown conference call number rather than the number they used to originally contact him, so the teammate did not answer the phone.

McKenna argues that by failing to hear from his teammate—whose testimony McKenna claims could have affected the alleged victim’s credibility—Duke violated his due process rights.

The initial appeal

On Sept. 2, 2016, a four-person appellate board determined unanimously that “procedural errors within the investigation or hearing process may have significantly affected the finding” from the first panel. In particular, the board cited the fact that the hearing panel did not address the reasonable person standard, which “must be considered for a finding of responsibility.”

Because the panel determined that McKenna’s own account indicated the female student did not provide clear and affirmative consent, it proceeded without the teammate’s testimony. The appellate board found no procedural errors in the failure to interview McKenna’s teammate.

Due to the “reasonable person” standard procedural error, the appellate panel returned the case of the Office of Student Conduct with instructions to correct the problems. In particular, McKenna objected to the possibility of a second panel considering the issue.

The members of the appellate board were chair Tim Bounds, senior director for strategic operations in student affairs; Linda Franzoni, associate dean of undergraduate education in the Pratt School of Engineering; Joe Gonzalez, dean for residential life; and David Rabiner, director of the Academic Advising Center and associate dean of Trinity College of Arts and Sciences.

A request for dismissal

As the Office of Student Conduct considered how to fix the procedural error, McKenna emailed Bryan Sept. 20, 2016 asking him to dismiss the complaint following an in-person meeting between the two earlier that day. In the email, McKenna argued that the initial hearing panel was not unanimously convinced that the female student said she did not want to have sex, so “that issue cannot be revisited by another hearing panel.”

Lastly, McKenna asserted that “no reasonable person could find that I engaged in sexual misconduct on the record now before you” in his request to have complaint dismissed.

Despite his arguments, two days after the meeting and email, McKenna was informed that the case would be going to a new hearing panel. The Chronicle has previously reported that Jerrica Washington, who was on the initial panel, is no longer employed at the University. In February 2017 testimony in court, Dean of Students Sue Wasiolek alluded to a panel member’s departure as a reason that an entirely new panel was needed, although she did not specify Washington in court.

James Coleman gets involved

After the Office of Student Conduct informed McKenna that they would be convening a new panel, James Coleman, Jr., John S. Bradway professor of the practice of law and faculty advisor to McKenna, sent an email to Duke administrators asking them to reconsider the decision. Per the conduct guide, students are allowed to have a trained disciplinary advisor for the proceedings.

Coleman was not involved in the case for the first panel, but he testified in court that he had been asked by the director of compliance in the athletics department to get involved in McKenna’s case after the appeal. Both Mary Giardina, director of compliance in the athletics department, and Todd Mesibov, assistant director of athletics for compliance, declined to comment.

Coleman, who later testified on McKenna's behalf during the court proceedings, is co-director of the Wrongful Convictions Clinic at Duke and chaired the Lacrosse Ad Hoc Review Committee, which was convened by President Richard Brodhead during the 2006 Duke lacrosse scandal to investigate the behavior of the lacrosse team.

His email was sent to Bryan; Larry Moneta, vice president for student affairs; Pamela Bernard, vice president and general counsel; and Chris Lott, associate university counsel.

In the email, Coleman makes several arguments on McKenna’s behalf, the first being that the new panel would constitute double jeopardy—a constitutional principle saying a person cannot be tried twice for the same crime. Although Duke has since argued that this constitutional principle does not apply to them as a private university, McKenna and Coleman argue it is nonetheless a principle of fairness Duke should follow.

Coleman argued that sending the case to a new hearing panel would allow the alleged victim to re-argue her case. Specifically, he said, the first panel had not been able to conclude she had said “no,” so a second panel should not be given the opportunity to decide otherwise.

Coleman called the decision to have a new panel “indefensible,” and added that he thinks Duke has a responsibility to protect the rights of all students, not just of alleged victims, in sexual misconduct cases. In asking Duke to “step in to avert this unfairness,” Coleman wrote that he seriously doubts the Office of Civil Rights, which he once advised as deputy general counsel of the Department of Education, would agree with Bryan’s decision.

The second hearing panel

The second panel, which convened Nov. 2, 2016, found the female student’s account of the alleged incident credible because of its specific details, according to its report. It unanimously believed her three claims—that she told McKenna she was a virgin when he reached for a condom, pulled away before sex and said no during intercourse. The first panel did not unanimously conclude that she said no during intercourse, but this panel did reach that conclusion.

The panel also noted that both McKenna and the female student agree that she told him she was a virgin before sex. As a result, the panel concluded that he “should have sought additional confirmation that the complainant wanted to engage in sexual intercourse.”

Another point the second panel made in its report is that McKenna’s argument that intercourse was consensual based on prior sexual conduct that evening was invalid. The sexual misconduct policy states “consent to one form of sexual activity does not imply consent to other forms of sexual activity.”

Although the first panel did not speak to the teammate McKenna claims had a sexual relationship with the female student, the second one did hear that player’s witness testimony before reaching a decision.

Like the original panel, the second one decided on a six-semester suspension. But its justification for that decision makes it clear that the second panel’s decisions were influenced by the original one, even though it was supposed to re-litigate the proceedings entirely without reference to the prior panel.

In a footnote, the justification for the six-semester suspension said that even though the second hearing panel originally decided on a 10-semester suspension, the Office of Student Conduct decided six semesters would be appropriate since the first appellate board found no errors with the initial process of implementing a sanction.

Because of this adjustment, McKenna argues in his filing that Duke cherry-picked which issues to re-litigate and which ones were already decided.

In addition to the suspension and being placed on disciplinary probation for the rest of his undergraduate career, McKenna would have been required to complete a therapy program aimed at sexual offenders to be eligible for readmission.

The chair of the second panel was Laura Andrews, assistant director of student life. Its other members were Shawn Lenker, a health, safety and security officer in the University’s Office of Global Education, and a current senior student. The panel’s facilitator was Valerie Glassman, assistant dean of students.

The second appeal

After McKenna appealed the second panel’s decision Dec. 16, 2016, a four-person appellate board—the same one that decided the original appeal—sent McKenna a response earlier this year on Jan. 25 informing him that it unanimously determined that there were no procedural errors within the second investigation and hearing process.

It claims that in convening a new panel, the Office of Student Conduct fixed the procedural error in accordance with Duke policy, because all of the original board members were no longer available. As noted above, Jerrica Washington had since left the University.

McKenna’s legal argument

McKenna’s lawyers filed a motion for a preliminary injunction, which was granted last Wednesday and allows McKenna to remain at Duke while further litigation takes place.

In a brief for his motion, McKenna’s lawyers lay out the following legal arguments. Citing various case law, the brief argues that the University is bound by written contract—both his financial aid agreements as a student-athlete and the Duke Community Standard—to follow its disciplinary procedures without deviation. They also argue that Duke has a duty of “fundamental fairness” toward its students.

One of the most significant aspects of McKenna’s argument is that the University violated its own procedures by calling a second panel to hear the case, instead of having the original panel or the appellate board make a final decision. Specifically, McKenna points to a passage from the 2015-16 sexual misconduct policy that only mentions sending the case back to the original panel.

“After its review, the appellate panel will resolve the case; or, if more information is needed from (an) additional witness(es), it will remand the case to the original hearing panel with instructions to call the witness(es) and to reconsider its decision in the light of that additional testimony.”

Supporting this argument, Emilia Beskind, a lawyer for McKenna, argued in court that this policy stands in sharp contrast to what had been in place just one year prior, in the 2014-15 policy:

“If the grounds for appeal are substantiated, the appellate panel may determine a final resolution to the case or refer the case back to the Office of Student Conduct for further review and/or a new hearing.”

Beskind said that until 2015, the University’s policy did allow for a second hearing panel, but that this policy had been consciously changed by the time McKenna actually matriculated in August 2015. The prior policy allowing a new panel could not be applied to him, Beskind argued, and the newer policy—which does not explicitly provide for a second panel—should have been used.

McKenna’s lawyers argue that Duke violated double jeopardy, which they contend is a basic principle of fairness.

Specifically, McKenna points to the conclusion of the original July 2016 hearing panel. Although that panel found that the alleged victim had not consented, it was unable to conclude whether the victim had actually said “no” as she claimed she had. His lawyers state that the first panel acquitted him on that second ground, and that the second panel violated double jeopardy by reconsidering “the issue in which the plaintiff previously prevailed.”

Finally, they argue McKenna would suffer irreparable injury if he were suspended, because he would be unable to make progress in his academic and professional soccer career.

Duke's response

The University, through attorney Paul Sun, filed a legal brief countering the motion for a preliminary injunction.

First, the brief argues that McKenna would not suffer any irreparable injury, because he would have been permitted to reapply to Duke after the six-semester suspension was carried out. The University also argued that speculative losses to a soccer career could not sustain an injunction.

Attempting to rebut McKenna’s argument that the second panel was invalid, the University pointed to the language in the 2015-16 policy giving the appellate panel power to “resolve the case.”

The University argued that “resolve the case” gave the appellate board the discretion it needed to send it back to the Office of Student Conduct to correct the procedural error, and that the Office is then permitted to decide whether or not a panel is necessary. This argument was based on language in the policy saying "a determination will be made by OSC whether sufficient information exists to move forward with a hearing."

Thus, Duke argues the Office of Student Conduct was fully entitled to create a second hearing panel.

The University also contends that the principle of double jeopardy would not apply to Duke as a private university, as the term is primarily reserved for the government’s criminal proceedings. But even if it were applicable, Duke nonetheless says McKenna’s double jeopardy argument fails.

According to Duke, even though the initial panel could not conclude the victim said “no,” it had nonetheless still found him responsible for sexual assault because it concluded she had not consented. This is in contrast to McKenna’s argument, which states he was partially acquitted by the first panel because it could not conclude she had said “no.”

Double jeopardy normally prohibits retrying someone after being acquitted, but Duke argues McKenna was never acquitted at all in the first place, and that McKenna was trying to “manufacture an acquittal” that did not exist by improperly “attempting to redefine his disciplinary case.”

Therefore, in Duke’s view of the case, there was no double jeopardy violation. The University also cited legal precedent to reach its conclusion.

Citing a 1981 Supreme Court decision, the University argues “there is no double jeopardy bar to retrying a defendant who has succeeded in overturning his conviction, unless the basis of the appellate court’s reversal is that the evidence was insufficient to convict.”

This, per Duke’s argument, corresponds to the appellate board remanding the case due to procedural error, which would be similar to vacating the conviction if this were a criminal proceeding. Because the appellate board remanded the case due to procedural error alone, case law would indicate that a second hearing was permissible, the brief concludes.

A second panel was especially appropriate, a supplemental brief contends, when it would have been impossible to reconvene the initial panel, which was due to Jerrica Washington’s departure from the University.

Hudson grants the injunction

During a five-day period, Hudson heard from witnesses about the case. Coleman’s testimony focused on the double jeopardy claim and also attempted to cast doubt on the alleged victim’s credibility by questioning her claim that she was a virgin.

Bryan testified that he had no vendetta against McKenna, as he felt McKenna’s attorneys were trying to insinuate. He also insisted that the sexual misconduct guidelines were not meant to lay out every course of action, but rather general principles.

Dean of Students Sue Wasiolek also testified, as did Tim Bounds, who chaired the appellate board. Wasiolek said that issuing an injunction would “take the teeth” out of the University’s disciplinary process.

But Hudson eventually sided with McKenna’s legal team and granted the injunction, allowing him to return to school while the lawsuit continues. Hudson deemed Duke’s procedures “fundamentally unfair.” After the decision, Beskind said she was looking forward to presenting their case before a jury.

A team spokesperson has since confirmed that McKenna is currently enrolled at the University and is still a member of the men’s soccer program.

Gautam Hathi, Claire Ballentine and Adam Beyer contributed reporting.