The February meeting of the Arts and Sciences Council could potentially bring a notable curriculum change—the removal of the foreign language requirement.

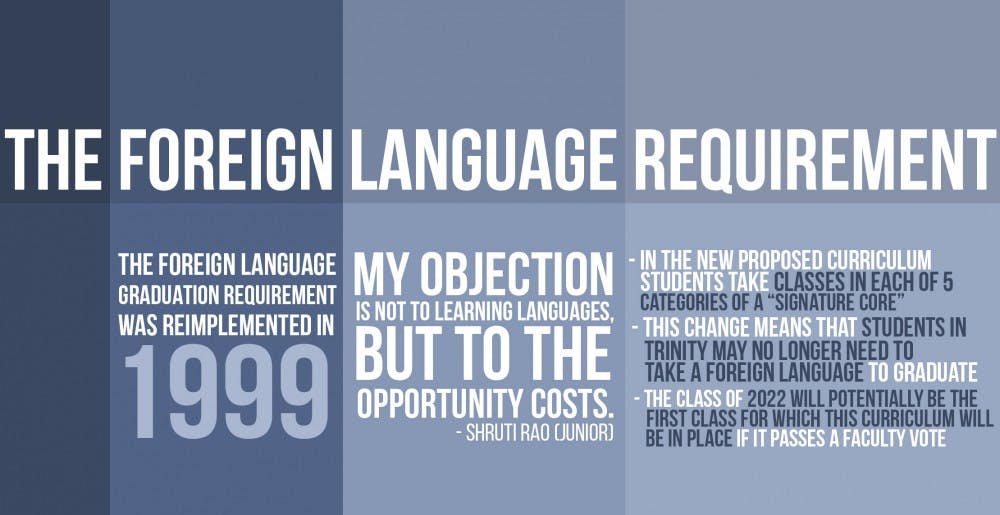

Requiring foreign language courses has been a hotly-debated topic since its reinstatement in the current curriculum approved in 1999, and the proposal to remove it has been met with mixed responses from faculty and students. The lack of information about how the proposal will be implemented has made discussion of its consequences murky, and some worry that it will shrink enrollments in certain departments.

In the current curriculum, all students in Trinity College are required to take foreign language courses—with the number corresponding to their proficiency in that language. Advanced students have to take one, and many beginning and intermediate students have to take at least three in order to fulfill a mode of inquiry requirement.

In the current draft of the new curriculum, students are required to take one course each in five different categories of the "signature core," one of which is a "Languages and Cultures" requirement.

Although languages would be one way to fulfill this requirement, students would no longer be required to explicitly take a foreign language course. Suzanne Shanahan—associate research professor of sociology and chair of the Imagining the Duke Curriculum committee, which was charged with drafting the new curriculum—confirmed this at the November meeting of the Arts and Sciences council.

The draft of the curriculum will be voted on by faculty in February after further deliberation and discussion, with the Class of 2022 potentially being the first class that the curriculum would be in place for.

Opportunity costs?

Proponents of the shift called into question the flexibility of the current requirement, the opportunity costs of having three required classes and, more broadly, the validity of using language requirements as motivators. Ingeborg Walther, a professor of the practice of Germanic languages and literature and a member of the IDC committee, added that many students already speak multiple languages.

“We are getting students coming to Duke now who are more diverse than ever. We have more international students, students from various backgrounds and minority students,” said Walther at December’s Arts and Sciences Council meeting. “We are trying to take into account designing structures for students to meet them where they are when they come in.”

Shruti Rao, a junior Program II major and columnist for The Chronicle who has previously written against the requirement, said that she takes issue with the implications of the requirement even though she has found her Italian course enjoyable.

“I don’t really understand where three semesters comes from, because you only have 34 classes here at Duke. For me, I take every single one of those classes as a serious learning opportunity,” she said. “I understand having a language requirement, but I think ours detracts from other interests the students want to pursue. My objection is not to learning languages, but to the opportunity costs.”

Trinity College does not have an option to place out of its language requirement through tests. Of several peer institutions, the University of Pennsylvania and Yale University do not exempt students from the language requirement through a placement test. Harvard University and Stanford University do allow students to opt out, however.

At Duke, the Pratt School of Engineering does not require foreign language classes, but does list them as one means of fulfilling a five-course social science requirement.

Opponents of the proposed change cited a link between language and culture that cannot be experienced in an English-speaking classroom, as well as the intellectual tools developed through language-learning.

Joshua Sosin, an associate professor of classical studies, said he believes the current three-semester requirement is actually too low.

“For many languages, the third semester is when you are just starting to get going, just starting to take the training wheels off,” he said. “The kind of way of thinking, of thinking about the world and the habits of mind that you acquire as you learn languages are rewards that are kind of slow in coming, but beautiful when you get there.”

Sosin explained that the classical studies department, which teaches Latin and ancient Greek, has kept track of its enrollment numbers since the early 1990s. The reintroduction of the language requirement with the current curriculum, he said, caused a sharp uptick in their enrollment numbers.

One concern is that the change will reduce enrollments and ultimately faculty employment in foreign language areas. Matteo Gilebbi, a lecturing fellow in the romance studies department and a member of the Duke Teaching First adjunct faculty union, wrote that he wanted more information about the proposal.

“We feel that we really don’t have enough information about how the curriculum would work in practice and impact our working conditions and our students’ educational experience to make a meaningful statement at this time,” he wrote in an email Sunday.

Will students experiment?

One student who used Latin as a gateway course is junior Gabi Stewart, who is the only classical languages major in her year.

“The reason why I picked the major is because the requirement forced me to take a language class, and I didn’t really know what to do," she said. "I was terrified of speaking a language. So I picked Latin, and I ended up just falling in love with the language. After a year of Latin, I decided to see if I liked Greek. Then I ended up deciding to major in the languages.”

Some faculty expressed concern that the removal of the requirement would inhibit students from stumbling upon areas of interest.

Martin Eisner, an associate professor of Italian studies and the director of graduate studies for the romance studies department, said he was worried students might not take language classes without the requirement.

“It worries me, but I don’t want to be apocalyptic,” he said. “One thing that might happen is that students might be less willing to experiment, which is what the whole curriculum is supposed to be about. If you could satisfy a language in an easy way, that students will take the easy way.”

Esther Gabara, E. Blake Byrne associate professor of romance studies and co-director of the Global Brazil Lab, said she is less worried about required languages and was more interested in fostering an appreciation of multilingualism among students.

Faculty also stressed the importance of language as a gateway to understanding other cultures.

“Learning a different language definitely helps you be empathetic,” said Letizia Montroni, a visiting lecturing fellow in the romance studies department and a Ph.D. candidate. “It’s challenging and uncomfortable, for most people, because you are left without the power of word. You have this urge to express yourself.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Bre is a senior political science major from South Carolina, and she is the current video editor, special projects editor and recruitment chair for The Chronicle. She is also an associate photography editor and an investigations editor. Previously, she was the editor-in-chief and local and national news department head.

Twitter: @brebradham

Email: breanna.bradham@duke.edu