When former Trinity Dean Laurie Patton asked the Arts and Sciences Council’s Curriculum Committee whether the Trinity undergraduate curriculum needed an update, faculty told her that it wasn’t broken enough.

“Until the situation’s really bad, you can’t create dramatic change,” said Suzanne Shanahan, who chaired the committee, about their thinking at the time.

The last major change to the arts and sciences undergraduate curriculum was in the late 1990s, when Curriculum 2000 was introduced. But although the Curriculum Committee found problems with the current curriculum, they didn’t initially conclude there was enough dissatisfaction to drive the years-long process of developing a new curriculum.

“From our perspective, a curriculum is a profound social, cultural change in a community,” Shanahan said.

But Patton, who is now president of Middlebury College, didn’t think that a significant problem was needed to improve the curriculum. Patton told the Curriculum Committee to rethink their answer.

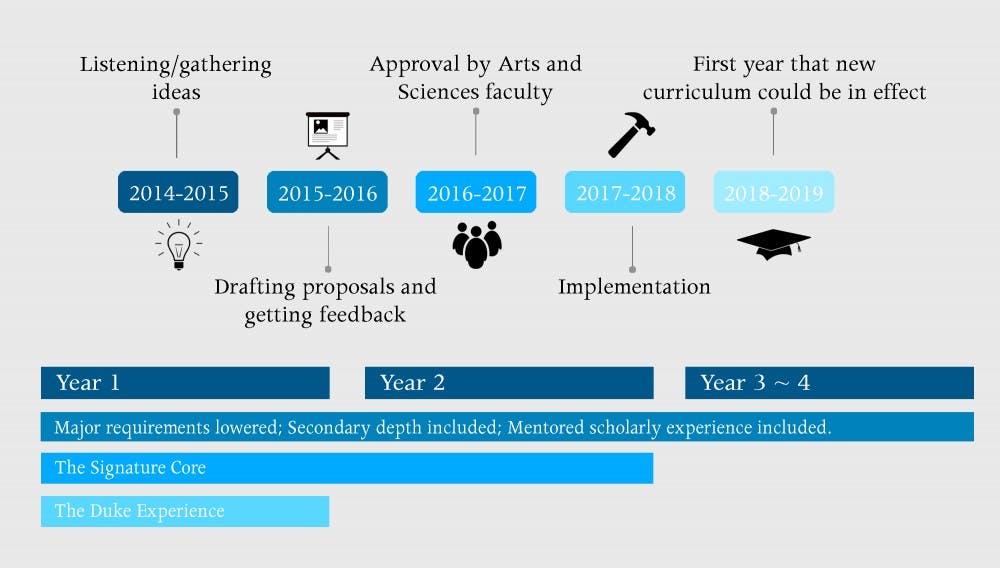

Shanahan and the Curriculum Committee eventually got onboard with a curriculum revamp, and so the Imagining Duke Curriculum committee was formed in 2014, also chaired by Shanahan. The IDC committee embarked on a three-year journey to rethink what Duke undergraduates are required to do during their time here.

After trying out a number of different ideas, including some radical departures from the current system, the committee is now closing on a final proposal. The final draft will be voted on by faculty in the Spring and, if approved, will move toward implementation next year—with the class of 2022 potentially being the first group of students to experience the new curriculum.

But obstacles still remain, and no one as of yet has found answers to key questions about how the new curriculum will be implemented.

‘Any crazy idea’

The process for building a new curriculum began with listening.

Ray Li, Trinity ’15, was Duke Student Government vice president for academic affairs when the IDC committee was formed. He helped Shanahan gather ideas for the new curriculum through a series of town hall meetings with students.

“What that looked like is that me and Suzanne Shanahan would have this thing once a week that we would call Town Hall where we would invite students from across the school to come meet with us,” he said. “That would usually be a group of maybe five to 10 students who would come. Undergraduates only since it was the undergraduate curriculum, and they’d be from Pratt, Trinity, from all different majors, all different affinity groups and different types of students groups that might want representation.”

Li added that Shanahan—an associate research professor in sociology and the co-director of the Kenan Institute for Ethics—would hold meetings with faculty members and academic departments.

At the start of the process, the goal was to get a general sense of what students and faculty were thinking as well as to collect a wealth of possible ideas to draw on, Li said.

“[We were] really finding out what the broad strokes were of what we wanted the curriculum to look like and then throwing out any crazy idea at the wall and seeing what stuck,” he said.

The one major theme that the IDC committee heard from students, Li said, was that the current curriculum was inflexible and counterproductive. Students also told Shanahan and Li that they were taking classes around the distribution requirements rather than engaging with them.

“We thought that [the current set of requirements] was too rigid, we thought that it led to too much of gaming of the system,” he said. “It was not really preparing students for what the administration thought the curriculum was preparing students for.”

From ideas to a proposal

To fix these issues, the IDC committee focused on a couple of ideas that came up during their discussions with students and faculty.

The first idea centered around special courses that were different from the standard catalogue offered by Duke. Li said that the IDC committee discussed a number of ideas, including “pop-up” courses that would start in the middle of a semester and focus on discrete skills, such as survival Arabic or basic programming.

However, the committee decided instead to focus on a new, year-long course for first-years. This program, tentatively named “The Duke Experience,” will be a collection of seminar classes clustered around a series of “themes.” New Duke students will have to choose one of these courses to take during their first year on campus.

The IDC committee also pursued a second, more radical idea that showed up in early curriculum proposals to faculty members, but which has been removed in the latest proposal. Responding to suggestions that the current curriculum is too structured and rigid, committee members discussed having a distribution requirement, but letting students decide with faculty advice whether a given course or program fulfilled a requirement.

In other words, Duke might require students to take a natural science course, but a student could argue that they had fulfilled the requirement by participating in a DukeEngage program or even by taking a literature course.

After significant pushback from faculty, however, this idea was scrapped in the most recent draft of the IDC’s curriculum proposal. Shanahan acknowledged that many faculty members found the idea of open requirements, which the IDC called “expectations,” to be unworkable.

“People felt rather uncomfortable with the logic of the expectations,” she said. “So we’re moving toward making those in some way required.”

Instead, the latest round of curriculum proposals would require students to take courses in five different categories during their first two years at Duke. These requirements are in place of the current set-up, in which students have to satisfy 11 different “Areas of Knowledge” and “Modes of Inquiry” requirements.

But students won’t be able to take just any courses to fulfill these requirements. Instead, they’ll have to pick courses from a “curated subset” of the course catalogue that will be “taught by Duke’s best faculty,” according to the draft proposal.

In addition, students will have to not only complete a major, but also a “secondary depth.”

Shanahan noted that 83 percent of students already complete a second major, minor or certificate, which would fulfill the secondary depth requirement. Students could also assemble a set of courses and other experiences, such as DukeEngage or DukeImmerse, which could then be approved by faculty to satisfy the requirement.

Lastly, the proposed version of the new curriculum will require students to complete a “mentored scholarly experience.” The definitions of what types of programs could fulfill this requirement are loose, but possibilities include a traditional capstone course, an independent study or a Bass Connections program.

Lynn Smith-Lovin, Robert L. Wilson professor of sociology and a member of the IDC committee, noted that giving students more control during academic exploration was a common thread.

“A central goal of the curriculum was to have students have more ownership and authorship of their scholarly trajectories at Duke rather than their doing it as a fill-in-the-blank structure,” she said. “Whether the proposals accomplish that, of course, is what we’re debating.”

Where does the money come from?

Many of the proposed curriculum changes have one thing in common—they will need an investment of additional faculty time and effort.

Both the new first-year “Duke Experience” course as well as the “curated subset” courses that students will be required to choose five courses from are slated to be taught by “Duke’s best faculty.” In addition, the mentored scholarly experience will also require extra time from faculty to focus on individual students.

At this point, however, neither the IDC committee nor administrators seem to know where the extra resources will come from. To compound the problem, Patton announced in 2015 that Trinity would be “constrained” in any new faculty hires.

“We cannot ‘afford’ our current faculty size,” she wrote in an email at the time.

Faculty members have expressed concern that that the new curriculum will not be properly implemented given the budget constraints that Trinity seems to face.

Bruce Donald, James B. Duke professor of computer science, wrote in an email that a current Trinity hiring freeze combined with other budgetary constraints makes him wonder where resources for the new curriculum will come from.

“It is great that Duke is ambitious and wants to do a lot of things,” he wrote. “But at the same time Duke is saying that certain units are impoverished and running a deficit, so why is it that new initiatives are being proposed for those units to accomplish? How will they be paid for? And as a corollary: what other important things cannot be done in order to achieve the curriculum reform, which looks expensive?”

Shanahan said that there is no firm plan at this point to provide resources for the new curriculum, but added that the focus at this stage in the process is determining the best ideas.

“We’ve talked a lot about different kinds of incentives and how to do that,” she said. “I think for us at this point the question is, ‘Is it a good idea? Do people think this is in the best interests of the best scholarly community that we could have here?’ And then let’s figure out how to make that happen.”

Valerie Ashby, dean of Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, said via an assistant that she did not have any time during the last several weeks to answer questions about the curriculum review in person or on the phone.

When The Chronicle emailed Ashby a series of questions about her role in the curriculum review process, faculty concerns about resources for the new curriculum and the future of the curriculum implementation process, Ashby explained that resources and the budget will be “worked out” once the curriculum is approved by faculty.

She provided the following statement as a response to all of The Chronicle’s questions:

“Thank you for reaching out about the new curriculum proposal. Let me see if I can answer your questions succinctly. Trinity College faculty own and shape the undergraduate curriculum and my role is to ensure that the Duke Curriculum Committee receives the support it needs. The committee, as you know, is made up of faculty members and this team has been honing ideas and feedback from the departments and the Arts & Sciences Council for more than two years. Once a new curriculum proposal is approved, we will then enter the implementation phase and can work out the details and budget needed to launch our refined approach for undergraduate education.”

Moving forward

Faculty feedback has already changed the curriculum proposals, and more feedback is likely to come during the next few months.

Some faculty members say that they have been encouraged by changes made to the proposals. Jeffrey Chase, professor of computer science, said that he felt the IDC committee was working well to address problems with the curriculum proposals.

“There were some faculty who had concerns with the result [of the review process], and so now they’re trying to resolve those concerns, which is probably the right thing to do,” he said. “It would be ideal if everybody voiced their concerns before the decisions were made, but this is probably the right thing to do at this point.”

Others, like Donald, are not sure that potential problems with the new curriculum have been resolved in the latest draft proposals.

“The budgetary questions that I raised have not been addressed at all,” he said.

In addition, it is not clear whether current students are aware of the proposed curriculum changes. Although the new curriculum will not affect currently enrolled students, the IDC committee has tried to get student input during the review process—mainly by holding events open to students and by coordinating with Duke Student Government.

DSG President Tara Bansal, a senior, noted, however, that there has only been limited outreach to students regarding the new proposed curriculum.

“Many of the decisions require a lot of conversation between administrators and faculty that know much more about academic pedagogy, so that decision making process can be slow,” she explained in an email.

Whether students are aware of it or not, faculty will vote on the new curriculum in the Spring, perhaps after making changes from the latest proposals. If the new curriculum is approved, however, the future of Duke undergraduate education may look significantly different than it is today.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.