Dr. Richard Bloomfield knows the experience all too well. Aside from being an assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Duke, Bloomfield has a daughter with autism.

And, like many other parents, Bloomfield initially struggled to make sense of his daughter’s behavior. Although she began to have challenges understanding social cues and interpreting others’ emotions at age 4, she did not receive a diagnosis until she was 6.

“As a first parent, your initial gut reaction is to assume that you’re doing something wrong or there’s something that you just don’t yet understand about your child,” Bloomfield said. “It can be hard to look at your child objectively.”

Autism is a neurodevelopment disorder that affects approximately 1 in 68 children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Although the disorder can be diagnosed as early as 18 months old, parents often do not identify less noticeable symptoms and receive a diagnosis for their child until he or she is older than four.

Even experts can sometimes have difficulty recognizing that a child has autism.

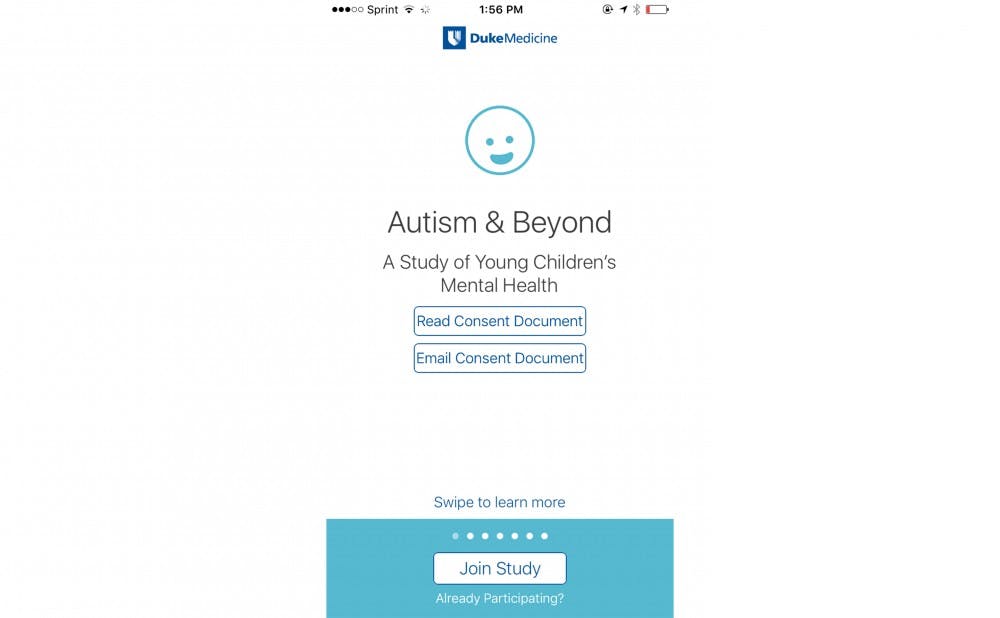

But the University’s Autism and Beyond mobile app is changing that. Launched in October 2015, the research app has helped thousands of people determine whether their children might be at risk for autism. Although Autism and Beyond is a study that does not directly screen for autism, researchers hope it will lead to the development of more mobile programs that can accurately diagnose and treat mental health disorders at earlier ages.

“Ultimately, we don’t want to just screen. We want to then be able to provide guided advice back about what to do, how to get help,” said Dr. Helen Egger, chief of Duke’s division of child and family mental health and neurology and a co-leader of the app’s development team. “We’re trying to really develop tools that take advantage of the computer in your pocket.”

Autism and Beyond is one of seven medical apps that are available to the public as part of Apple’s new ResearchKit. It is part of a growing trend that has seen the release of different mobile healthcare apps, including EpiWatch—which helps people with epilepsy track seizures.

Duke’s autism app relies on questionnaires and video analysis of facial movements. When parents first open the app, they come across a series of eligibility questions and other facts about the study. Once the test begins, children watch three videos that are based on the same exercises that psychologists use to diagnose autism. The clips show toys that involve moving balls or women singing “Itsy Bitsy Spider” or “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.” As the child stares into the iPhone screen, the app uses the phone’s front camera to record and examine facial expressions.

Parents can then send the video and analysis to researchers, who use a computer algorithm to quantify the emotion detected in the child’s facial responses. The app also provides parents with feedback about the child’s risk of having autism and suggestions for dealing with different behaviors that might be an issue.

Autism and Beyond originated from the PRIDE Study, which Egger and Duke autism researchers launched in 2014. In that study, Egger said her team tested whether pediatricians could use an iPad camera and video stimuli to more efficiently determine whether a child could have autism.

Although it worked well, the PRIDE Study examined just 100 kids from Duke’s pediatrics department and was not readily accessible. Egger needed more evidence that the video analysis tool could be reliable.

Autism and Beyond has met those criteria. The app is scalable and user-friendly, and since its launch a year ago, more than 2,300 people have participated in the study.

“The difference between doing something when people come into a clinic setting versus providing an opportunity for parents to participate in research in the comfort of their own home is a big difference,” Egger said.

Guillermo Sapiro, professor of electrical and computer engineering who helped develop the app, said the device that records facial expressions has been successful.

“We have demonstrated that the tool is as accurate as experts,” Sapiro wrote in an email.

He added that his team is preparing a paper that discusses the proof that actions recorded at home can be used for screening.

Although it remains just a test, Bloomfield—who is also the mobile technology strategy director for Duke Medicine—said the app is allowing parents to detect and treat autism sooner. In addition to the difficulty of recognizing autistic behavior, people often cannot afford to have their children examined for autism. In fact, many remote areas do not even offer access to mental health professionals who can diagnose autism, Bloomfield said.

And delays in autism diagnoses can be costly. Early intervention and treatment can minimize some of the side effects of the disorder and also put parents more at ease, according to the Autism Speaks organization.

“Having a diagnosis much sooner will help parents take better care of their children and be more patient with them and help them be as successful as they can be,” Bloomfield said. “Being apart of this will help other parents to avoid that anxiety.”

That is why the creators are also trying to introduce the app overseas. The research team has focused on building partnerships with other medical centers around the world to increase access to the application. Egger said the University of Cape Town in South Africa has relied on Autism and Beyond to expand its autism research, and in Argentina, Duke’s researchers are working to create a Spanish version of the app.

“Healthcare is only going to improve as we learn better ways and more efficient and effective ways to take care of our patients,” Bloomfield said. “Tools like this are going to help get us there. We clearly need to expand.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.