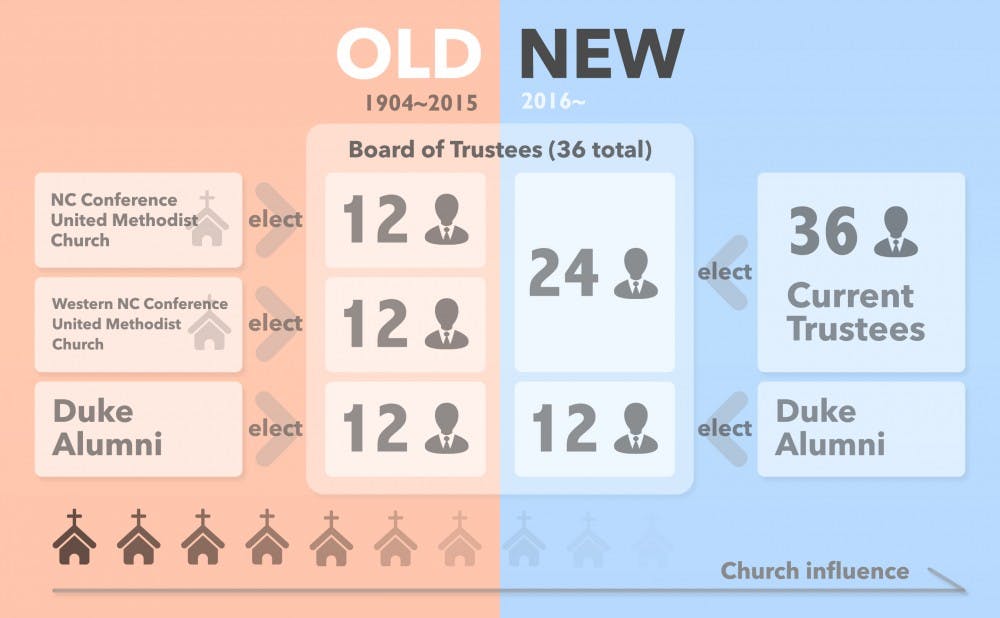

Effective this year, none of Duke’s Board of Trustees members will be elected by the Methodist Church.

The North Carolina and Western North Carolina Conferences of the United Methodist Church have together traditionally ratified 24 members of the Board, although only after a majority of the Trustees recommended the candidate. Now, however, any future group of Trustees will be elected without confirmation from either church. Twelve members will continue to be elected by Duke alumni. Members each serve six-year terms, and no Trustees can serve more than two consecutive terms with renewed eligibility following two years absence.

“The bylaws were changed earlier this year and take effect with the next group of Trustees to be elected to the board,” wrote Michael Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations, in an email. “It was done in consultation with the conferences and with the support of the current and immediate past Trustees from the United Methodist Church.”

In two statements, the conferences noted that their leadership had been involved in the decision.

Derek Leek, director of communications for the North Carolina Conference, and Michael Rich, web and communications manager at the Western North Carolina Conference, noted the University and churches will still interact.

“We continue to share and cherish our Methodist connection with Duke University in this time in more appropriate and mutually helpful ways,” Leek wrote in a statement.

Schoenfeld noted that although the Trustees' charter gave the Conferences electoral power, in reality the churches just ratified the Trustees' own nominations. No one can join the Board without the Trustees' approval of the candidates first, he said.

The shift will not change much about the University, Schoenfeld explained, noting that Duke retains its “historic relationship” with the Methodist Church. Funding from the Divinity School will still be provided by the two conferences.

Charles Clotfelter, Z. Smith Reynolds professor of public policy studies, echoed that idea. He explained that many elite universities are moving away from their religious affiliations.

“It’s a trend that has been happening over time, and it’s most visible in the nonprofit colleges, the ones that are name-brand prestigious and nationally,” Clotfelter said.

Before it become Duke University, Trinity College and its precursor institutions were influenced by an informal, primarily-Methodist leadership, according to a history written by University Archivist Valerie Gillispie. The College’s 1891 charter was the first to specify that 24 Trustees must come from the two church conferences.

However, Duke's former charter did not mandate the Trustees to be affiliated with the church—just ratified by it, Gillispie wrote.

Former Duke President John Kilgo later worked in 1903 to change the process so that the Trustees all had to be recommended by a majority vote of the Board’s current members before approval by the two conferences. This practice reduced the influence of the Methodist Church on the school, Gillispie wrote in her summary.

In North Carolina, Davidson College and Wake Forest University used to be much closer to the Presbyterian and Baptist churches, respectively, Clotfelter explained. That changed during the past several decades as the colleges sought more autonomy.

Clotfelter said he did not think the University moved away from the Methodist Church for legal reasons, although other colleges have faced legal hurdles due to their religious affiliations.

For example, Davidson was the center of a 2011 lawsuit about whether the college’s use of a police force violated the First Amendment’s separation of church and state. The lawsuit alleged that, because of Davidson's religious affiliation, the police force was not legally permissible. However, the North Carolina Supreme Court found that state law permitted the college to maintain a police force.

At least a quarter of Davidson's trustees are required to be members or affiliates of the Presbyterian Church.

Although Clotfelter noted that he believes the decision fits into a society that is increasingly secular or non-denominational, he also said not to discount the continuing role of the religion on colleges.

“The fact that that these things are officially coming to an end should not make anyone blind to fact that religion will still be important,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Adam Beyer is a senior public policy major and is The Chronicle's Digital Strategy Team director.