Some scholars believe that grade inflation has become prevalent at Duke and many other universities nationwide.

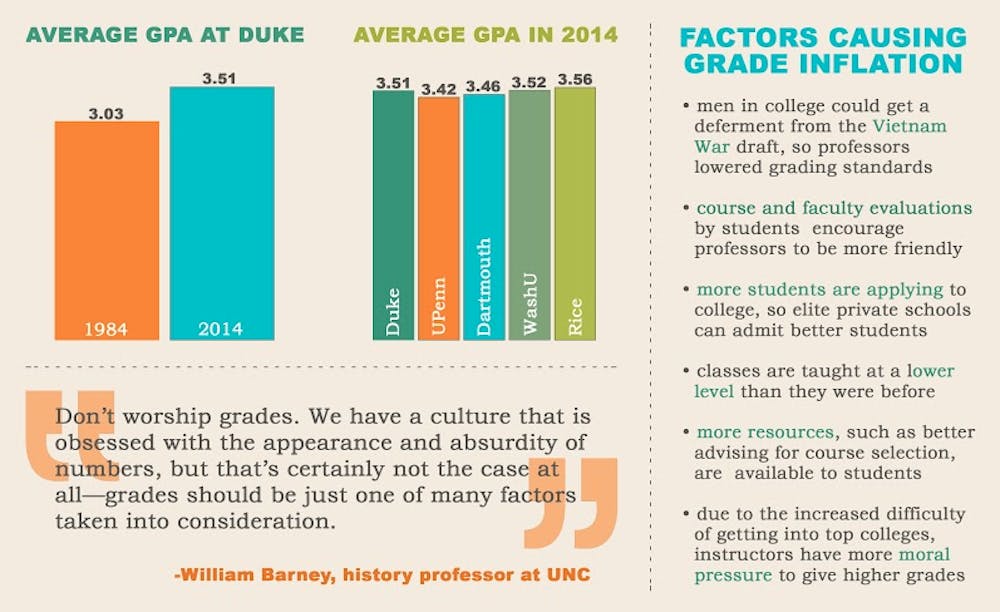

According to Stuart Rojstaczer, a former Duke professor of geology and earth and ocean sciences who now publishes research about grade inflation, the average GPA at Duke in 2014 was 3.51, a marked increase from 3.03 in 1984. This trend is the same at many four-year colleges, which have an average GPA of 3.15. At private institutions, the average GPA is more than two-tenths of a point higher than at public colleges, with GPAs averaging above 3.3. However, Lee Baker, dean of academic affairs for Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, noted that counteracting grade inflation may hurt students.

“When universities challenge grade inflation, it never hurts the strongest students—they’re going to keep getting A’s,” Baker said. “Any change would impact students that are in the middle or lower third of the class, and we recognize that those students are also exceptional.”

Baker explained that he feels the University has a responsibility to support all its students, so it would be unfair to penalize students “who are working hard to bring their C’s up to a B or B’s up to an A-.”

At 3.51 in 2014, Duke’s average GPA is relatively high compared to private colleges overall but not when compared to peer institutions. According to Rojstaczer’s data, the average GPA in 2014 was 3.42 at the University of Pennsylvania, 3.46 at Dartmouth College, 3.52 at Washington University in St. Louis and 3.56 at Rice University.

“The anomaly at Duke likely is due in large part to a real change in the quality of student over [50 years], as it evolved from a regional to a national and global university,” wrote Warren Warren, James B. Duke professor of chemistry, in an email.

The evolution of grade inflation

Modern grade inflation is the product of a number of factors. In the 1960s, the average GPA at Duke was as low as 2.41. This began to change during the height of compulsory enlistment for the Vietnam War.

“Young men in college at the time could get a deferment, so that made them a very precious commodity,” said professor of English Victor Strandberg. “I and other faculty members were more lenient in our grading standards so as to help [keep] our students from being drafted.”

The overall grading scale was pushed up to not penalize the grades of females who could not be drafted, Strandberg noted.

Rojstaczer explained that the advent of course evaluations has also turned the college education into a commodity.

“The biggest driver of grade inflation today is the consumer ethos on college campuses. That's present everywhere,” he wrote in an email. “People try to make claims that rising grades are mostly due to better students, technology or better teaching. I'll be blunt. Those claims are baloney.”

Some professors said they feel that the weight of influence given to students because of their evaluations is dangerous and puts the faculty in a difficult position.

“It’s not the evaluations per se—evaluations can be interesting, sometimes informative and often entertain meaning,” said Susan Wolfson, professor of English at Princeton University. “But when they’re weaponized to do damage, that encourages professors to be more friendly.”

William M. Reddy, William T. Laprade professor of history, said he believes that course evaluations can be a conflict of interest because professors “who are complacent about grading tend win high marks from students.”

Other professors proposed different factors that have led to continued grade inflation.

“As more kids go to school, the absolute number that can get into an elite private stays the same,” Baker said. “So there’s a mathematical realization that unless the number of spots increases at the same time as the population, you’re going to get increasingly better and better students.”

Reddy explained that grade inflation happens not necessarily because of the increased quality of the student, but because the moral pressure on instructors to give better grades is higher due to the increased difficulty of getting into a top college.

Additional factors may also play into the perception that students are getting smarter.

“At least in the sciences, we and everyone else teach classes at a lower level today than we did one or two decades ago because students like easier classes and review them more favorably,” Warren wrote.

Baker also noted that he thinks students have become more shrewd, in part due to an increase in resources available.

“It’s a combination of better advising which leads to more savvy course selection, reduced number of 'weed-out' classes and course objectives so everyone knows where they stand,” he said, adding that there is likely a correlation between the rise in class withdrawals and grade inflation.

The debate

Professors disagreed on whether grade inflation is a problem or a byproduct of the academic system.

Grade inflation misleads and penalizes the best students in today’s academic environment in which most students do not go beyond what is expected of them, Rojstaczer wrote. According to Rojstaczer, about 60 percent of all letter grades were A’s among Ivy League institutions.

“Most students aren't working hard, yet A is the most common grade,” he wrote. “Rigor is lacking. Students who want to get a great education—and there are quite a few who do—have to fight through the lethargy of their classmates to have thoughtful class discussions.”

Paul Escott, Reynolds professor of history and former dean of the college at Wake Forest University, agreed that the quality of students has not impacted grade inflation.

Escott wrote in an email he considers grade inflation to be a serious problem since students do not try to improve when awarded high marks. The problem is rooted in a culture that favors success and pushes away mistakes, he wrote.

Many faculty members admit that the proliferation of inflated grades has a number of consequences.

“It becomes difficult to quickly discern distinction between individuals,” Baker said. “But more importantly, it fuels the competitive nature of Duke students, where they curate their GPAs so carefully that they don’t take risks because a C or a D really will impact their GPA.”

Strandberg, who has taught undergraduates since 1962, noted the existence of a slippery slope with the hiring of younger faculty, who were educated after the Vietnam War and therefore were exposed to grade inflation themselves. Instructors can no longer distinguish between the extraordinary and the very good, he said.

Even so, a number of professors feel that grade inflation is not an issue when considered in the context of the modern day academic and post-graduation environment.

“The upshot is that grades just aren’t very important indicators anymore,” Wolfson said. “People who are reviewing transcripts don’t rely on GPAs as reliable indicators anymore because they understand the grading range tends to be compressed, particularly in the top half of the range.”

William Barney, professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, noted that formal numbers mean little beyond getting the student through the door of employers or graduate schools.

Additionally, grading is the most unpleasant part of many professors’ jobs, Strandberg said. Grade inflation makes things easier by alleviating the “absurdity” of having to distinguish between an “A- and an A or B+.”

Still, the continued rise of average GPAs at institutions nationally has led to calls for actions to halt or impede its progress.

In 2004, Princeton University adopted a grade deflation policy that limited university departments to giving no more than 35 percent A’s. The policy was repealed in 2014 by a majority faculty vote.

Douglas Massey, professor of sociology at Princeton University, wrote in an email that he “never liked” the policy.

“Why should faculty be expected to arbitrarily assign C's to high achieving students who performed well enough to earn an A?” Massey wrote. “Grade inflation is not a problem of lenient or soft-hearted faculty. It is built into the system through the selective nature of the admissions process.”

A call to action

Whereas some professors view grade inflation as natural, others feel it is necessary to take some action.

“Administrations have to wake up and realize that students are not consumers—and neither are their parents—and that the mission of educating is a serious and unique one,” Crossley wrote in an email.

Warren proposed a simple response to offset the effects of grade inflation.

“Personally, I would like to see the average grade for each class appear on the transcript right next to the grade the student received in the class,” he wrote. “That would not prevent a professor from assigning a high average grade, if he or she felt the class deserved it; but it might make comparison of a B+ in a class with an average grade of 3.0, to an A- in a class with an average grade of 3.8, somewhat fairer.”

Warren’s proposal is similar to a policy adopted at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2014 which contextualizes letter grades by providing the median grades and percentile ranges of the whole class.

But as the average GPA at elite private institutions begins to top 3.5, it appears that the academic world will have to respond to the phenomena some time soon.

“Eventually, I’m sure there will be a national conversation,” Baker said. “From Trinity College’s perspective, that’s not going to happen in the near term.”

At Duke, like many of its peer institutions, the administration has been hesitant to take drastic action regarding grade inflation without a national backing. Even modest suggestions incur opposition from both the faculty and the students, Warren wrote.

“Don’t worship grades,” Barney said. “We have a culture that is obsessed with the appearance and absurdity of numbers, but that’s certainly not the case at all—grades should be just one of many factors taken into consideration.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.