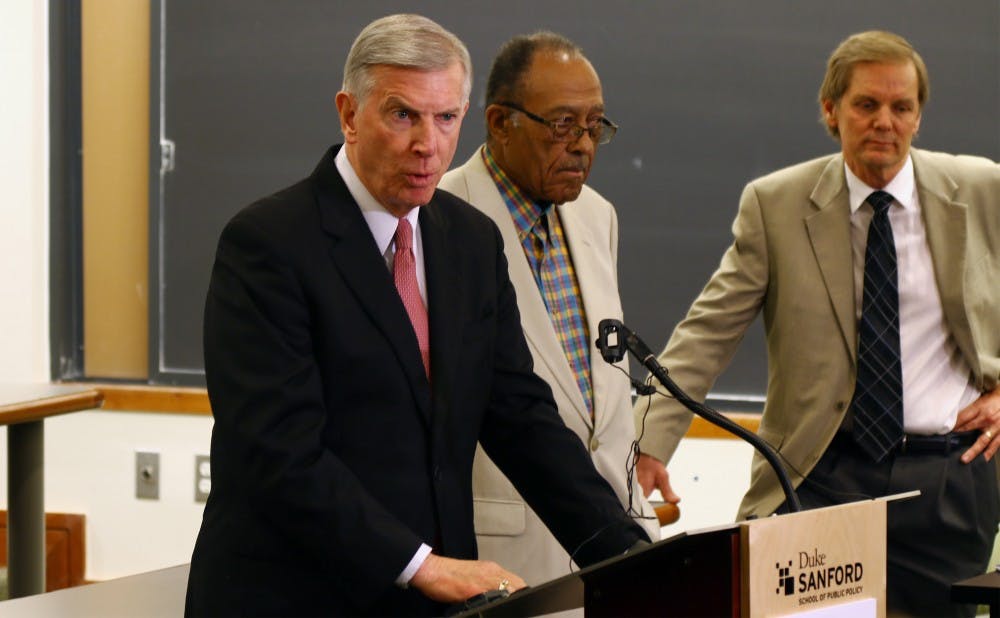

Retired North Carolina Supreme Court judges and political experts gathered Thursday at the Sanford School of Public Policy to discuss redistricting possibilities for North Carolina.

The panel was the first of three events for the “Beyond Gerrymandering: Impartial Redistricting for North Carolina” forum, which will result in a new but unofficial map of North Carolina congressional districts. The discussion of North Carolina’s gerrymandering problem began in February after the North Carolina Supreme Court upheld a lower court decision requiring North Carolina legislature to redraw a new district map for congressional seats after it was determined that two districts were racially gerrymandered. The event was designed to simulate an independent, nonpartisan redistricting panel.

"If you look across the country, there are some states that have truly what they call independent commissions, that draw the districts and those districts are the ones that are applicable for the election so the legislature is completely out of the process," said Thomas Ross, president emeritus of the University of North Carolina system and Terry Sanford distinguished fellow.

Alaska, Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana and Washington all utilize independent commissions to draw both state and federal districts and limit elected officials’ role in congressional district mapping. The members of these commissions have historically not been legislators and have been prohibited from running for office in a district for a specified period of time.

The notion that North Carolina should enlist an independent commission to draw congressional district lines has been recently discussed amidst legal battles over legislative redistricting in the state. Ross noted that an independent commission is possible solution that could be further discussed among the panelists.

“One of the things that we are trying to do here at Duke—and we hope this process will highlight—is there are different ways of [redistricting], and we need to examine all of them and find a way that might work best for any particular state, including North Carolina,” Ross said.

Ross explained that backup commissions can also be used to draw congressional districts. However, they take place after legislative review, unlike advisory commissions, which are consulted before maps are sent to the legislature for review.

“There is generally a process in the ones I have seen where there is a minimum equal number of selections made by legislative leadership in each party—the majority and minority party of each house in legislature,” he said.

Ross noted that in Iowa, backup commissions draw maps if the legislature cannot reach an agreement. This commission does not take into account factors like incumbency and party registration because Iowa's demographics require less attention than they might in other states.

"You can go through the process of an independent fair commission that doesn’t consider partisan politics and draws the districts but then you have to look at the Voting Rights Act to be sure that you are complying with it,” he said.

It is important to keep the issue of gerrymandering in consideration and to explore different methods to fix the problem, Ross noted.

Henry Frye, former chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, said that he hopes the panel will increase the public's understanding of redistricting.

“First of all, this is something that needs to be approved and we could sit back and complain about but instead we are saying let’s try and see if we can offer something that will encourage people to know more about how its being done in other places and the possibilities for North Carolina,” he said.

As of 2014, the Census Bureau reported that North Carolina was 71.5 percent white, 22.1 percent black, 9.0 percent Hispanic and 1.6 percent Native American. With an increasing number of black constituents, the first and 12th congressional districts have faced allegations that they were intentionally filled with black voters to lessen the impact of African American votes in other parts of the state.

“We need to have some sort of clarity on voting rights and the race issue,” noted Robert Orr, former associate justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court.

Redistricting in North Carolina is guided by additional rules that try to limit gerrymandering, protect incumbents and minimize partisan interests. The state constitution’s requirement that counties be kept whole—which was decided in the Stephenson v. Bartlett case—attempts to limit the occurrence of gerrymandering.

Bob Phillips, executive director of the non-profit lobbying organization Common Cause North Carolina, noted that because of the changing demographics in North Carolina, the district lines drawn in 2011 will likely change in 2020.

“Whether the demography is favoring one party or another is sort of a question mark, but the election and the changing demographics, we think, are two other factors that might make this more of a receptive environment for decision makers to look at,” he said.

Correction: This article was updated to correct the state demographics from 2014. A previous version of this article included percentages for the entire U.S. The Chronicle regrets the error.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.