Researchers at Duke have been accused of withholding clinical data used to evaluate the blood thinner drug Xarelto.

The accusations are part of a lawsuit brought by patients who claim to have been hurt by the drug rivaroxaban—known by its brand name Xarelto, a blood thinner first tested at the Duke Clinical Research Institute in a 2011 clinical trial known as the ROCKET AF trial. Pharmaceutical companies Bayer and Johnson & Johnson supported the trials of Xarelto and are the defendants in the lawsuit.

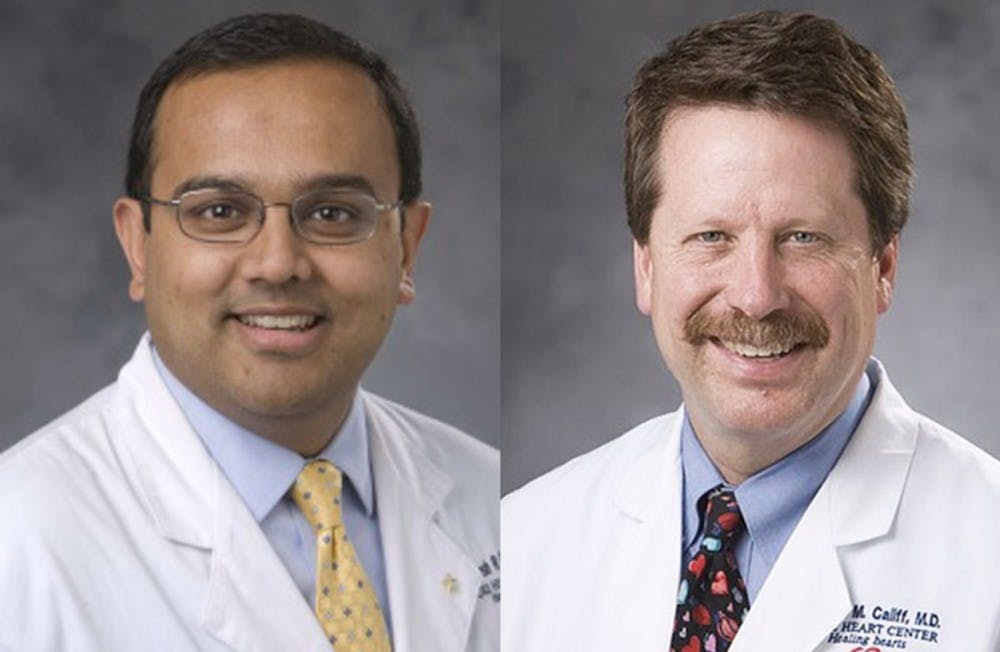

The original 2011 clinical trial—published in the New England Journal of Medicine and headed by Dr. Manesh Patel, member of the DCRI and associate professor of medicine, and Dr. Robert Califf, founding director of the DCRI and current commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration—found Xarelto to be more effective than the standard prescription of warfarin in reducing the likelihood of ischemic strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation, or abnormal heart rhythms.

The validity of the study, however, was called into question in 2014 when pharmaceutical sponsors Bayer and Johnson & Johnson revealed that the INRatio blood monitoring devices used to evaluate the effectiveness of the drugs studied in the ROCKET AF trial were not functioning properly. Dr. Christopher Granger, a professor of medicine at the Duke University Medical Center and member of the DCRI, explained that the INRatio device may have underestimated warfarin’s efficacy and therefore might have caused warfarin to be given at a higher dose in certain populations. That may have led researchers to unknowingly conclude that Xarelto was the more effective blood-thinning agent in the trial. The prosecuting legal team behind the Xarelto lawsuit alleges that these inaccuracies could have compromised the findings of the study.

In order to determine whether the faulty INRatio device truly did impact the results, Patel, Anne Hellkamp, a senior biostatistician at the DCRI, and Dr. Keith Fox, a professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh, submitted a letter in February to the NEJM with a re-analysis of the ROCKET AF trial data, concluding that the incorrect blood monitoring data did not impact the study’s conclusions.

According to a report in The New York Times, however, some in the medical community have questioned the techniques used in the re-analysis, claiming that the authors of the letter essentially had to guess which patients might have been tested through the malfunctioning INRatio devices.

The report claims that researchers said comparing the faulty device’s data with blood test results taken 12 and 24 weeks after the trial began would have been a more effective method of determining which patients were impacted by the INRatio device.

When asked in February about the clinical utility of the 12- and 24-week blood data by a reporter from The New York Times, Jeffrey Drazen, editor-in-chief of The New England Journal of Medicine, responded that he was unaware such data existed. These factors have led lawyers representing the plaintiffs of the Xarelto case to suggest that the letter’s authors attempted to deceive the journal’s editorial team. In The New York Times, Drazen maintained that the data was not relevant to the published letter and thus its omission was not an act of deception.

Patel and Hellkamp declined to comment for this article. Susan Landis, head of strategic communications at the DCRI, however, responded with a statement on their behalf. She wrote in an email that the DCRI ultimately did not feel the 12- and 24-week blood data was relevant for the re-analysis in question.

“I think we need to clarify the reason for the analysis, as no steps would be taken in this situation because scientific misconduct is not the issue here, and no one is asserting otherwise,” she wrote. “The ROCKET AF Executive Committee continues to discuss additional analysis of the trial data, including the blood data taken at 12 and 24 weeks and, as is our practice as an academic institution, we will make any analysis public.”

Granger was involved in a similar study published in 2011 that compared the effectiveness of the drug apixaban against warfarin. He said that this ongoing debate might be over-stressing the clinical importance of the faulty INRatio blood readings.

“The bottom line is that from everything we know, compared to all of the challenges that we have in doing large trials, this particular issue of [the INRatio measurements] is not relevant to the interpretation of the results of this trial,” he said.

He added that critics may have felt that artificially low readings would result in prescribing too much warfarin in certain patients and might have resulted in more patients bleeding in the warfarin portion of the study, which would have made Xarelto look safer than it really is.

“That actually turned out not to be the case. If anything it was the opposite,” Granger said. “In populations where there might have been a problem, warfarin looked safer, which would be totally inconsistent with the hypothesis that’s being raised. There are lots of other issues that are critically important, but this is not one of them.”

According to The New York Times, the plaintiffs’ lawyers have also suggested that the pharmaceutical sponsors Bayer and Johnson & Johnson may have played a role in recent events. Last fall, Bayer submitted an analysis, which included the 12- and 24-week blood data, to the European Medicines Agency that used a similar approach to the NEJM letter submitted by the scientists from Duke and Edinburgh. This information has also been submitted to regulators in the United States.

After investigating the clinical trial, the EMA released a report containing its own analysis, which was in agreement with the notion that the INRatio data did not significantly impact the study’s results and stated that there was “sufficient evidence to conclude that the benefit/risk balance remains unchanged and favourable for treatment with rivaroxaban.”

According to Digital Journal, however, the FDA has noted that the EMA committee that re-evaluated the clinical data was partially composed of DCRI members, which some claim to be a conflict of interest.

Stephen George, Duke professor emeritus of biostatistics and bioinformatics and editorial board member of the Journal for the Society of Clinical Trials, explained that omitting less crucial data is often necessary to maintain brevity when presenting clinical research to academic journals.

“It’s a judgment issue on what data you find important and what’s not,” he noted. “To say that every piece of data that’s collected in a clinical trial has to be reported in some way just doesn’t make sense. It’s not possible or even relevant to put everything in a paper.”

George added that although journals may not receive the full data from a trial, regulators such as the FDA can request access to almost any part of a study’s resultant data. Trial sponsors and companies typically consult with the FDA when designing a study to determine what data the FDA would like to analyze, he explained.

Granger said that he felt the biggest issue currently is that many patients with atrial fibrillation at risk for stroke are often not being treated with any type of anticoagulant such as warfarin and rivaroxaban. Granger added that although rivaroxaban and three newer drugs have been shown to be more effective in reducing complications, it is most important that patients take some type of medication.

“[Many of us] are in this interesting situation where we’re not just doing research that’s funded by pharmaceutical companies and the government and foundations, but we’re also applying those results in treating people in the Duke community, so it’s a very important perspective on how we should be interpreting results and applying treatments,” Granger said. “But the most important thing is to have patients treated with something to prevent stroke. So many people are not being treated with anything.”