While cultural and racial diversity have recently received significant attention, administrators are also working to acknowledge and improve socioeconomic diversity at Duke.

Students from lower-income backgrounds face unique challenges that administrators say they are trying to address through programs for first-generation college students created to help them adjust to life on campus. Administrators said that such programs are important to ensure that students from lower-income families have a place at Duke—especially in response to the University's perception as being for primarily upper- and middle-class students.

“We have to be aware that we will do best if we can make students from different backgrounds feel they belong here,” said Steve Nowicki, dean and vice provost for undergraduate education.

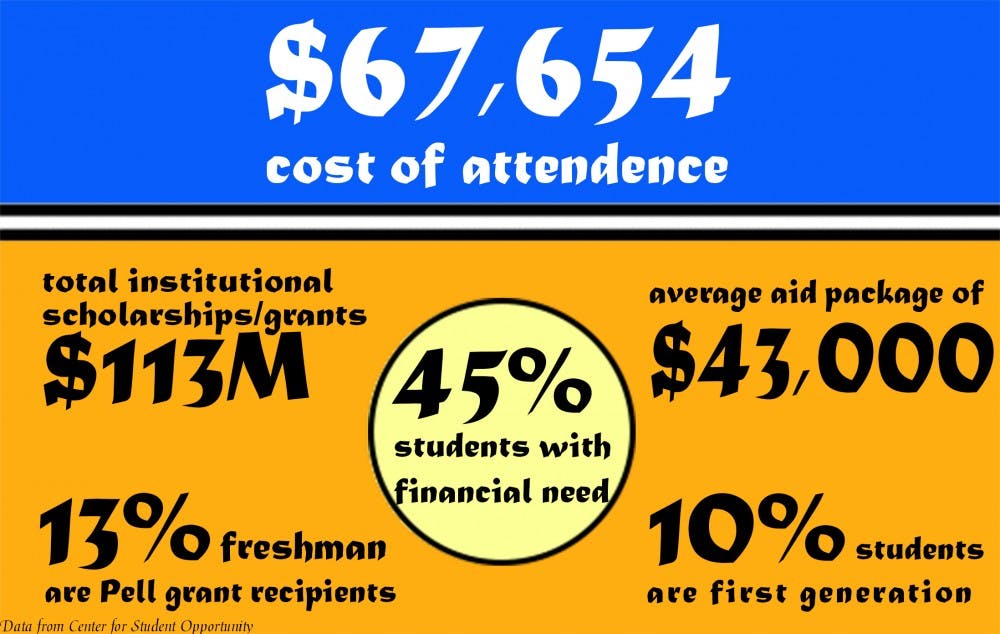

Half of the student body receives some form of financial aid, and 10 percent are first-generation college students, Nowicki said, adding that an open discussion of Duke's socioeconomic diversity openly would greatly benefit students.

Justin Clapp, director of access and outreach, said that Duke’s perception as a wealthy institution often hides students from less wealthy economic backgrounds who might be struggling with belonging or isolation.

“They’re carrying around additional baggage that no one can really see,” he explained.

As a remedy, Clapp manages programs designed to help low-income and first-generation students get comfortable with the distinct university environment. One such program is two-day pre-orientation called “1G” that gives students a chance to meet with peer advisors and mentors prior to the academic year.

Nowicki—who described the program as “Duke 101”—said that many first-generation students lack the social and cultural capital to succeed initially.

The pre-orientation is supplemented by continued events throughout the year, Clapp noted, including enrichment trips and student-led conversation series. The goal is to give students a safe space to discuss their unique issues, he explained.

Sophomore Ashley Ericson, who participated in 1G, said that the program allowed her to build not only a community of students but also of parents.

“It created a network of people that I could trust,” she explained.

In addition to first-generation students, Clapp also works with non-first-generation students who are not the first in their families to attend college but still struggle financially.

Programs like Duke Engage—for which no student is required to pay—are intentional ways the administration has sought to include lower-income students.

“We wanted to have no separation between the haves and have-nots,” Nowicki said.

Sophomore Ana Galvez—another 1G participant—agreed that Duke is taking steps to level the playing field for students from different economic backgrounds.

Nowicki said that he thinks that the University has been able to create an economically diverse student body because it is one of a decreasing number of schools that can truly claim to be need-blind and fully committed to meeting demonstrated financial need. Duke has to do more than simply admitting lower-income students, he said, adding that diversity without inclusion is ultimately meaningless.

One of his key goals is making sure that conformity is not a prerequisite for inclusion so that students can fit in with campus culture on their own terms.

“Inclusion needs to involve a serious discussion of differences,” he said. “People don’t have to agree about how life is but need to be able to discuss it.”

Nowicki noted that studies have shown that students who interact with others from diverse backgrounds report greater gains—including higher GPAs and increased salaries—after graduation.

“My interest in socioeconomic diversity is not just to help the poor kids but because everyone will benefit,” he explained.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.