Editor's Note: This is the second of a two-part series examining online education at Duke. Today, The Chronicle looks at the future of online courses for credit and unique uses of the massive open online courses. In Part 1, The Chronicle assessed how Duke has already brought digital education to the physical classroom.

As Duke continues its involvement with online education, administrators face questions of how courses might be counted for credit and how new adaptations might be brought to the physical classroom.

Each semester since Duke’s initial partnership with Coursera in Fall 2012 has seen the addition of new massive open online course offerings, or MOOCs. The growth of online education has been met with measured optimism by students and faculty alike, said Lynne O’Brien, associate vice provost for digital and online education initiatives. Although early results have been largely positive, student engagement will continue to depend on the way professors construct their classes—online or on campus.

“Positive responses have typically come when faculty have been able to keep the total workload the same as a traditional class,” O’Brien said. “I’ve heard criticism when students perceive that somehow the courseload has been greatly expanded, or if the in-person part hasn’t been designed well and it ends up just being more lecture…or if it doesn’t feel like they’re making good use of class time.”

The growth of online education will also depend on continued innovation of the ways that online classes are offered to students.

Rethinking credit for online courses

Two years ago, the idea of for-credit online courses was first broached in terms of a partnership with online education company 2U. The proposed plan would have joined Duke with seven other universities as part of a consortium that would offer for-credit courses through a program known as Semester Online. At the time, faculty expressed concerns about the choice of platform as well as the pedagogical techniques and a perceived dilution of the Duke degree, ultimately voting to reject the proposal. Semester Online was disbanded less than a year after the vote was held.

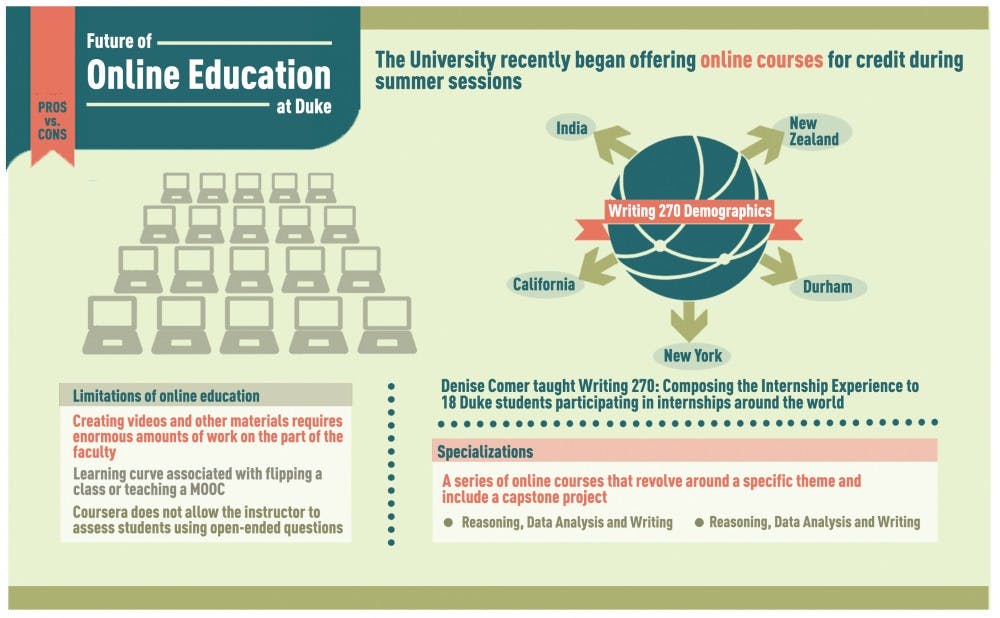

Since the vote, faculty and administrators have continued to discuss the topic of for-credit online classes—and some are embracing the idea. Although there are no immediate plans to introduce this type of course during the academic year, the University recently began offering fully online courses for credit during the Summer sessions, including four courses in Summer 2014. Students and faculty in these classes do not meet in person, instead interacting through various online resources such as chat rooms, video hangouts and blogs.

Last Summer, Denise Comer taught “Writing 270: Composing the Internship Experience” to 18 Duke students who were participating in internships around the world.

“We had students who were in New Zealand and Durham and California and New York and India,” said Comer, assistant professor of the practice of writing studies. “We met weekly through Google Hangout. They also reflected on their work experience through blogging and a variety of social media.”

The class will be offered again next Summer, Comer said. There are no plans to make any significant changes to the course structure.

“We’re not going to scale it like a MOOC,” Comer said. “It’s not going to be me teaching thousands of students. It’ll still be with 18 students—because it’s for Duke and it’s for credit, and we want that close instructor-learner relationship.”

Expanding the boundaries of the MOOC

As some professors tinker with smaller online seminars for credit, others are looking into new ways to use the MOOC.

The University has started to create “specializations”—series of online courses that revolve around a specific theme and include a capstone project. Specializations, which were introduced as MOOC courses by Coursera this year, will also include certificate tracks that students can pay to take. In the future, these could be used to target specific professional or academic audiences, O’Brien said. Duke has plans to offer two specializations—“Reasoning, Data Analysis and Writing” and “Perception, Action and the Brain”—with more to come in the future. These classes will not serve as substitutes for on-campus programs, although there may be integration between the two, O’Brien said.

“We will try to offer a set of related courses with the capstone experience rather than having every course be a complete standalone,” O’Brien said. “In the year ahead, we’ll be looking for other ways to do groupings of things that showcase places where Duke is strong, or showcase Duke’s interdisciplinary approach to teaching—to say that this is the kind of place Duke is.”

Some classes offer students the opportunity to create their own materials for MOOCs. Dalene Stangl, professor of the practice in statistical science, teaches one such class as part of a Bass Connections program.

“We’ve got our students actually doing videos as a central part of the course,” Stangl said. “These are undergraduates who are doing videos on teaching statistical software.”

Once these videos are produced, they will serve as the foundation for future classes on that topic, Stangl said. Additional videos or revisions may be made as they become necessary. Ultimately, Stangl said, the goal is to have a self-contained set of materials that can be accessed at any time as opposed to being on a schedule.

Room to grow

Several faculty pointed out that, despite the numerous innovations developed, online education has inherent limitations. Creating videos and other materials requires enormous amounts of work on the part of the faculty, and there is a definite learning curve associated with flipping a class or teaching a MOOC. In addition, Coursera does not allow the instructor to assess students using open-ended questions because there is no way to fairly grade thousands of subjective answers.

“I’ve got to do all multiple choice exams,” Stangl said. “I despise multiple choice exams, but it’s what the platform allows.”

Still, the expansion of online education at Duke has the feel of inevitability.

“An increasing number of classes will have some online component to them,” O’Brien said. “This is partly because so many incredible materials are being developed—not only at Duke but at other schools—that it’s hard for me to imagine not taking advantage of the stuff that’s out there.”

In the meantime, faculty who have had experience with MOOCs and flipped classes will continue to refine the ways they teach these kinds of classes.

Dorian Canelas, assistant professor of the practice in chemistry, leads a Bass Connections team in conducting research on the effectiveness of MOOCs and other styles of online education. Topics of interest include the qualitative experience of students in MOOCs and the low completion rates of online courses.

Duke may be able to expand its reach with online classes, but ultimately the lessons learned in those classes will be applied to improve the experience of students on campus, O’Brien said.

“Longer term, I think it’s likely that Duke will be looking for ways to give students more flexibility in their curriculum by allowing some blend of in-person and online courses,” O’Brien said. “Let’s say you got really fired up about some kind of lab experience and wanted to do more than just a semester of a lab, or you got excited about Duke Engage and decided you want to pursue that project for a longer time. Those are opportunities that you can only get by coming to Duke—I think having a mix of more things you can do online will let students do more of those sort of high-value, personal types of activities.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.