Staring at the viewer from his 1933 “Self-Portrait (Myself at Work)” is Archibald J. Motley Jr., a painter who here, donning a navy beret, long triangular mustache and thick tan bohemian jacket, paints a nude woman. His room has a few relics: a small cross on the wall, an elephant statue, a small bottle of alcohol and a palette spotted with bold and blended paints.

This is Archibald Motley, whose boldly colored Harlem Renaissance-era paintings chronicled the African American experience of the Jazz Age. Yet despite a 40-year span of significant artwork, Motley is one of the least visible artists of the 20th century. For the first time at the Nasher Museum, “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist” will be on display, with works dating from 1919 to 1960. The exhibition will also incorporate historical documents and audiovisual components, including a documentary commissioned by the Nasher.

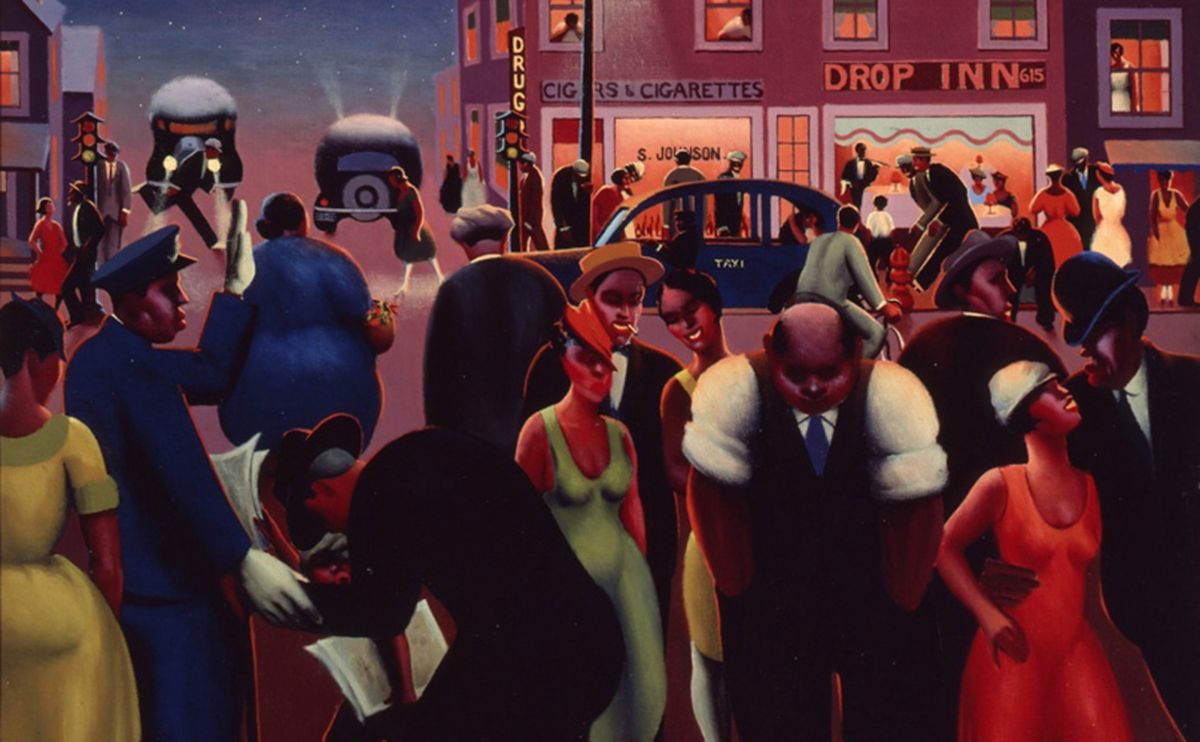

The work represents, in a radical and vibrant way, the communities Motley grew up in. Much of his most notable work is centered upon Chicago, particularly upon a neighborhood termed the “Black Belt” by outsiders and reclaimed as “Bronzeville” by its predominately black residents. Motley’s depictions of Chicago scrutinize both poor, overlooked workers from the South and the African American elite; yet throughout, there is a reimagining—a lauding of ambition. Here was a community in the midst of becoming, moving forth through modernity, forging black cultural and economic self-determination; and here was Motley in the middle of it all.

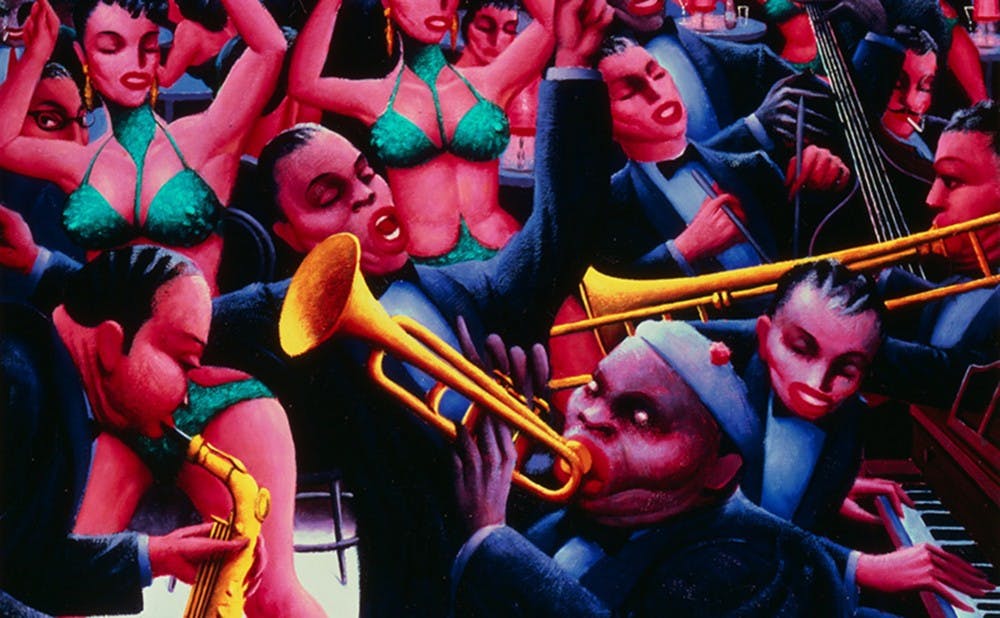

In “Street Scene” (1936), a woman wails in song, arms lifted and high-heeled feet spread wide apart. A dog howls, three women chorus with trumpets, one man blows into his trombone. The onlookers look more uncertain, more suspicious. A white police officer glares out of the corners of his eyes, and a small child cocks her head and watches. Motley’s work captured “black expression” while it was being cultivated and expanded. There were nighttime trumpet players, a rowdy nightclub, a Negro cabaret, picnics, cocktails, cards. A social outsider who looms and watches, absorbing the vibrancy and the energy. Each painting has this sort of observer, cementing Motley as someone caught up in the very center of this frenzy, as an outsider looking in, as a re-imaginer.

When Motley visited Paris, where African American artists had come to thrive (think Duke Ellington and Josephine Baker), he painted the blues, the idyllic Parisian streets and the Jockey, a café frequented by artists. When he visited Mexico, he continued with his pattern of over-the-top portrayals, following the same hint of mocking dark humor as in his "Hokum" work.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.